Biffs and Brawls: Tintin the Scrapper

Tireless hero, sharp-eyed detective with a strong sense of justice, Tintin is not just the young reporter with the rebellious quiff, driven by honesty and curiosity. He is also, perhaps more than one might think, a skilled combatant, a bold scrapper, capable of defending himself with a kind of energy and composure that commands admiration. He confronts danger with the same determination with which he roams the globe, and when words fail, fists take over.

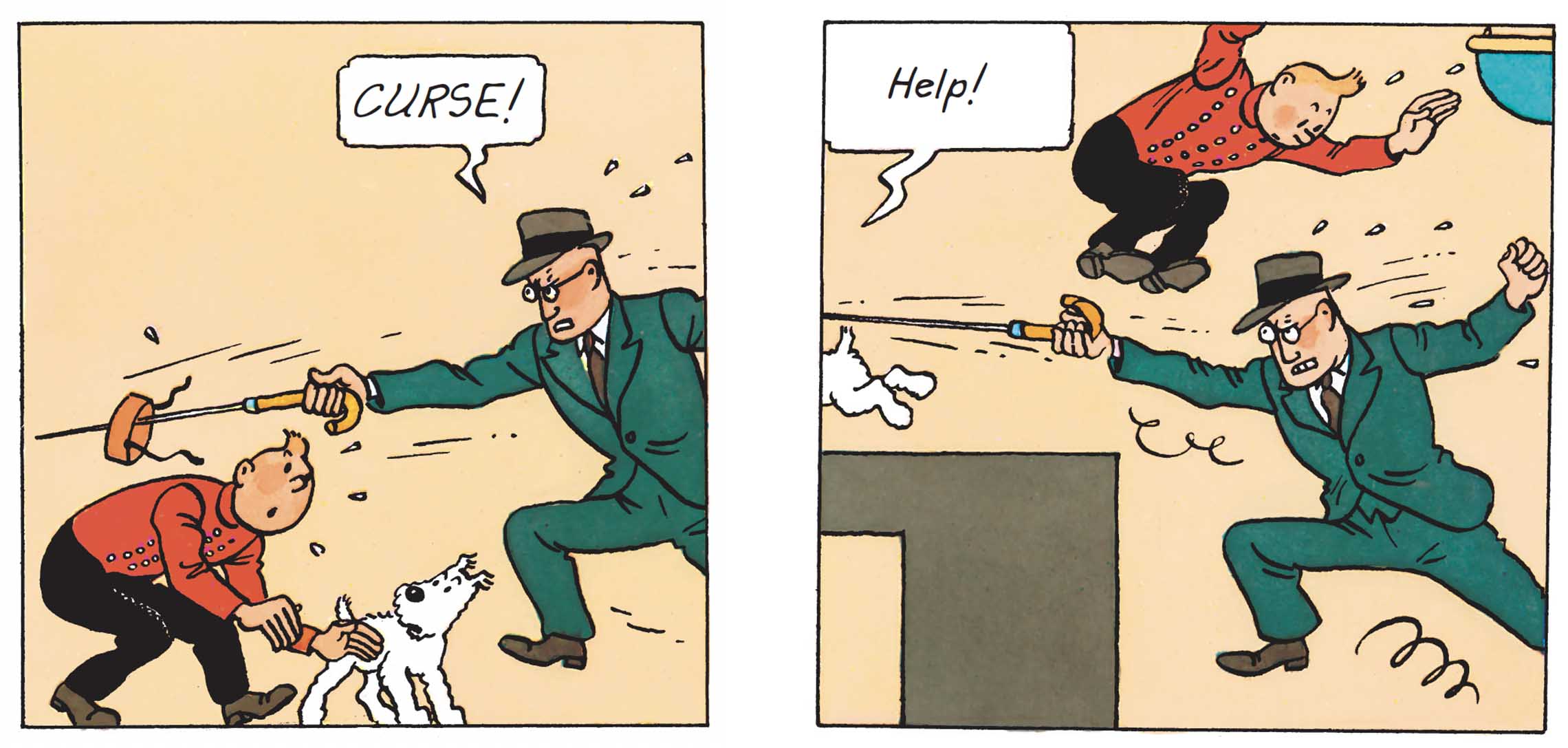

Barehanded, he takes on opponents stronger than himself, never giving in to despair; armed with a stick, a broom handle, or a revolver snatched from the enemy, he improvises, strikes, disarms, and topples his foes. His fluid silhouette moves through the fray, pummeling henchmen and assorted thugs, sometimes almost unconsciously, but always driven by moral resolve and unshakable loyalty to his companions.

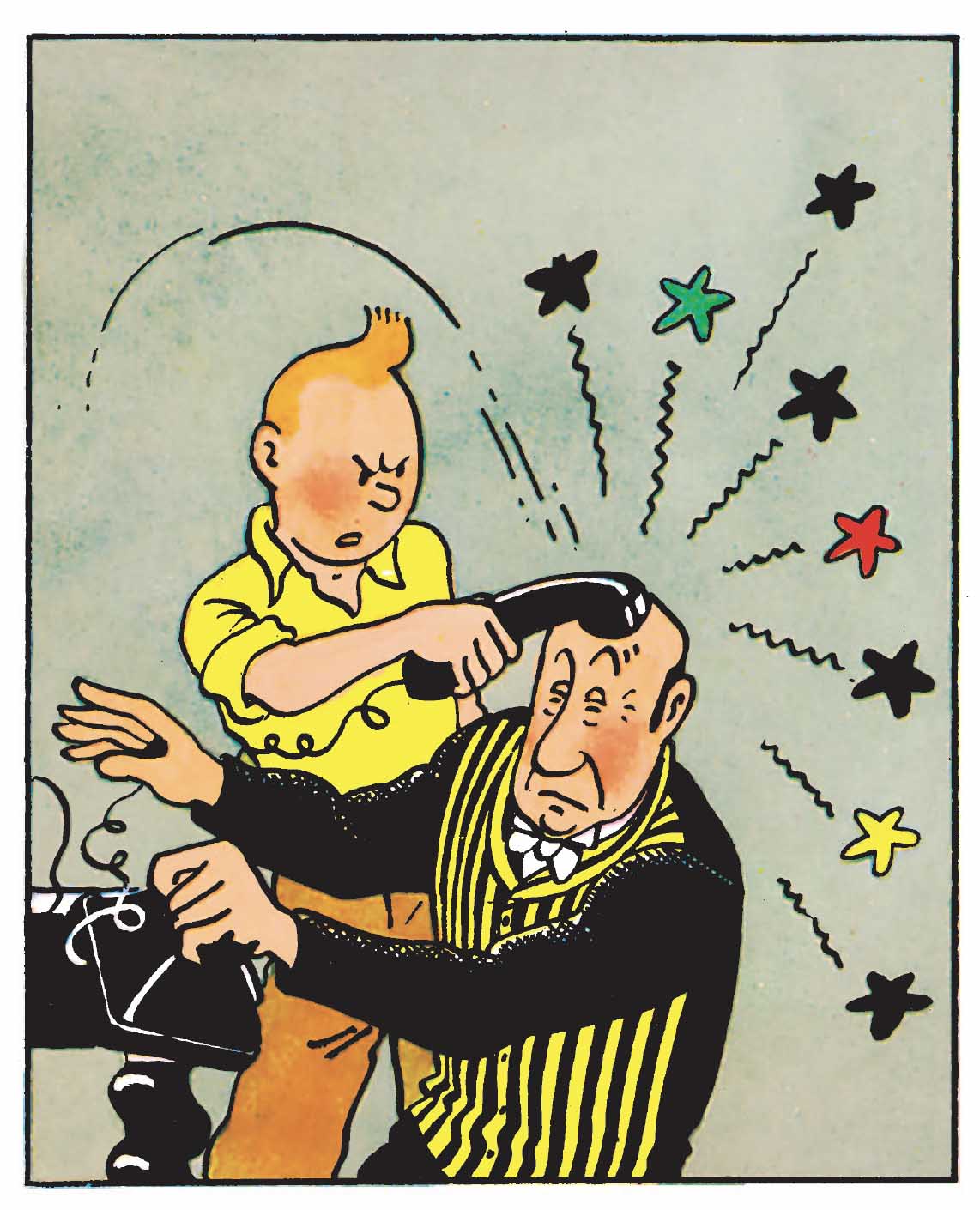

Only when necessary, Tintin dishes out uppercuts, hooks, and slaps as responses to brutish mugs, unscrupulous goons, and disguised traitors. In Tintin, bravery and pugilistic elegance come together. A dossier/essay told through punches!

"We didn’t come here to butter toast!" (1)

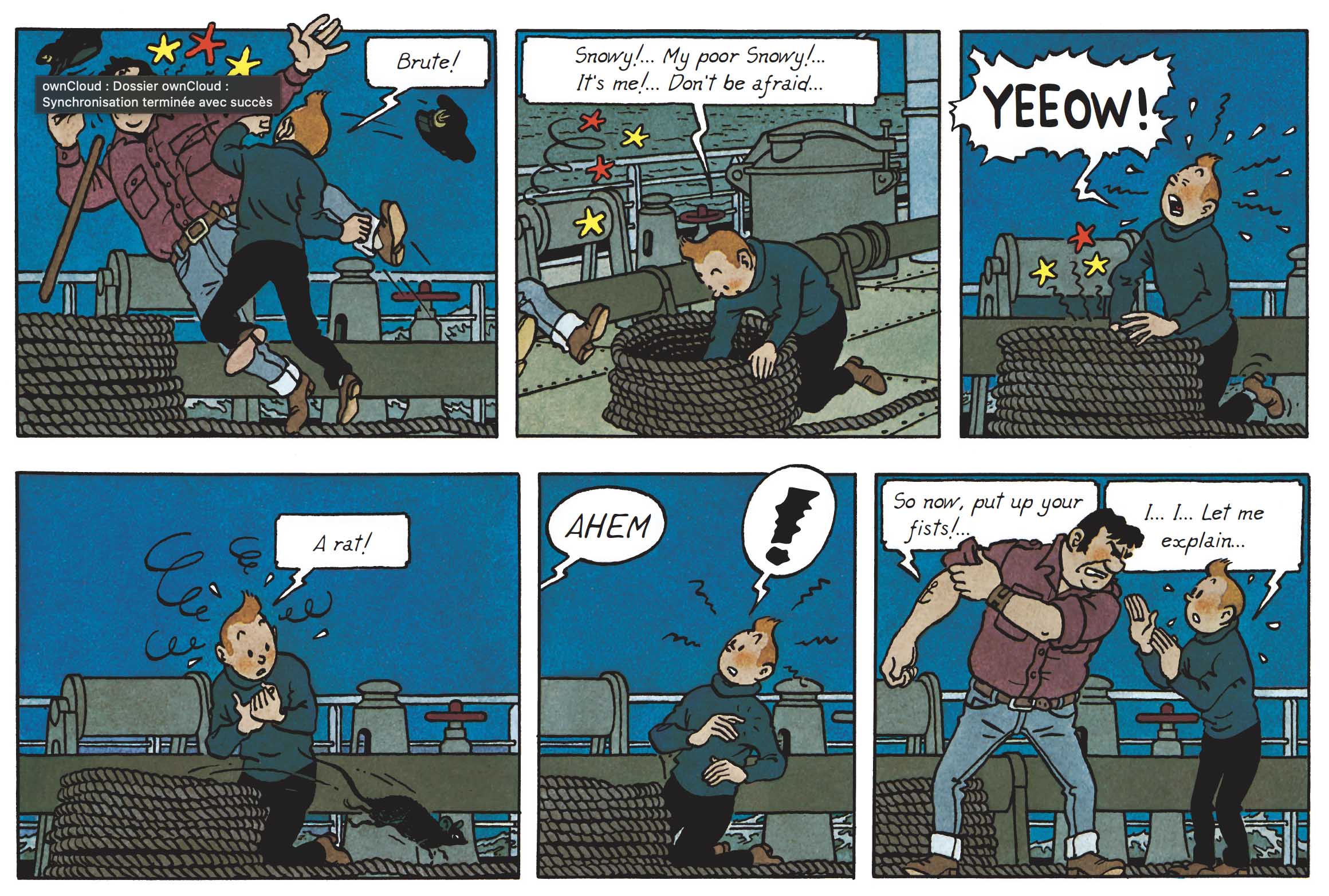

Since 1929, the Tintin series has joyfully combined adventure, mystery, humor, and suspense, never shying away from physical confrontation. From early punches to duels staged like elegant visual ballets, fights are a key part of the narrative, generating tension, catalyzing unexpected turns, but always toned down, never fatalistic.

Let’s admit it, though: Tintin takes his fair share of beatings. The kind that leave a mark on the body and the spirit. One word seems to echo like a bell throughout his adventures: "knocked out."

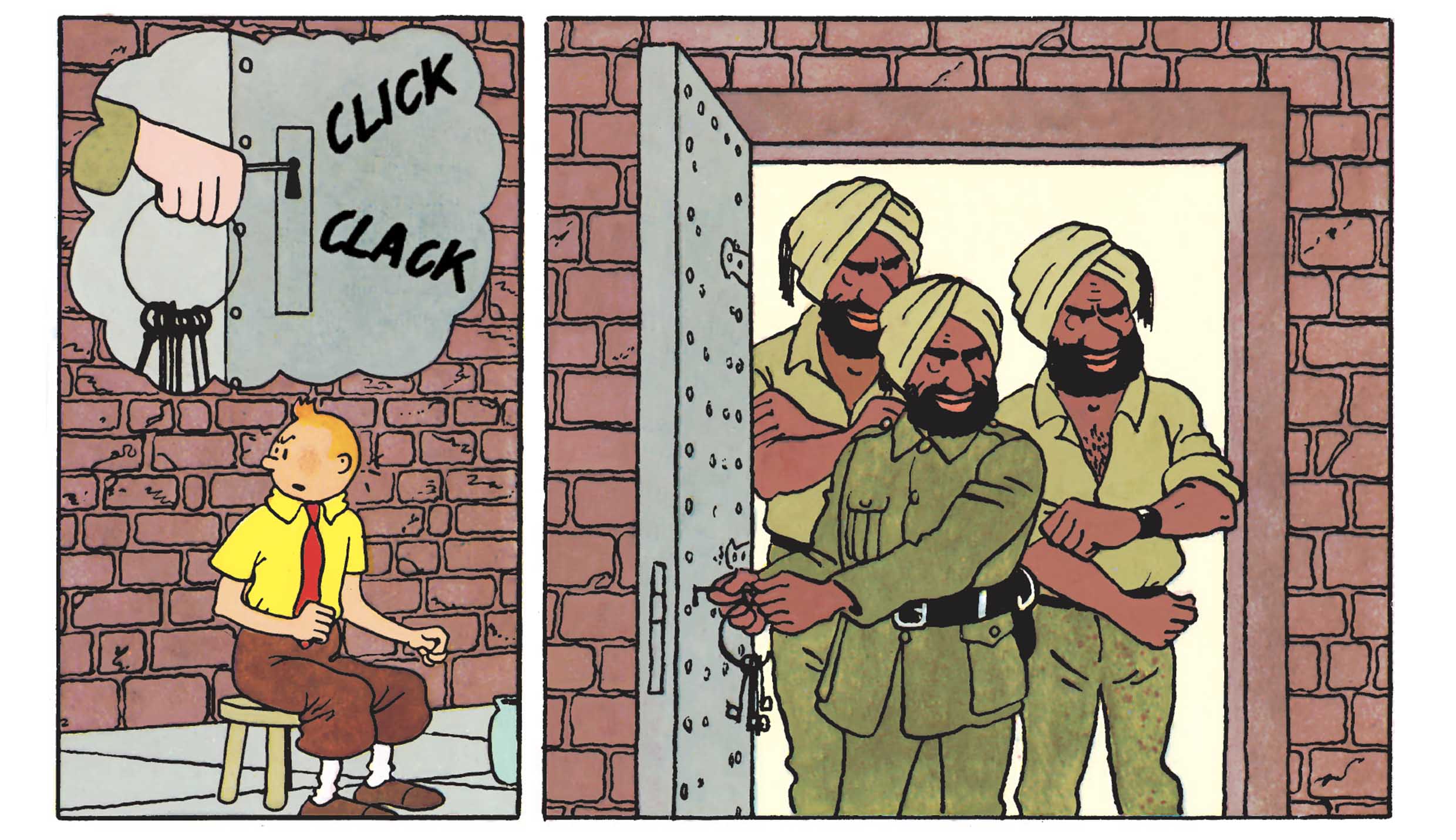

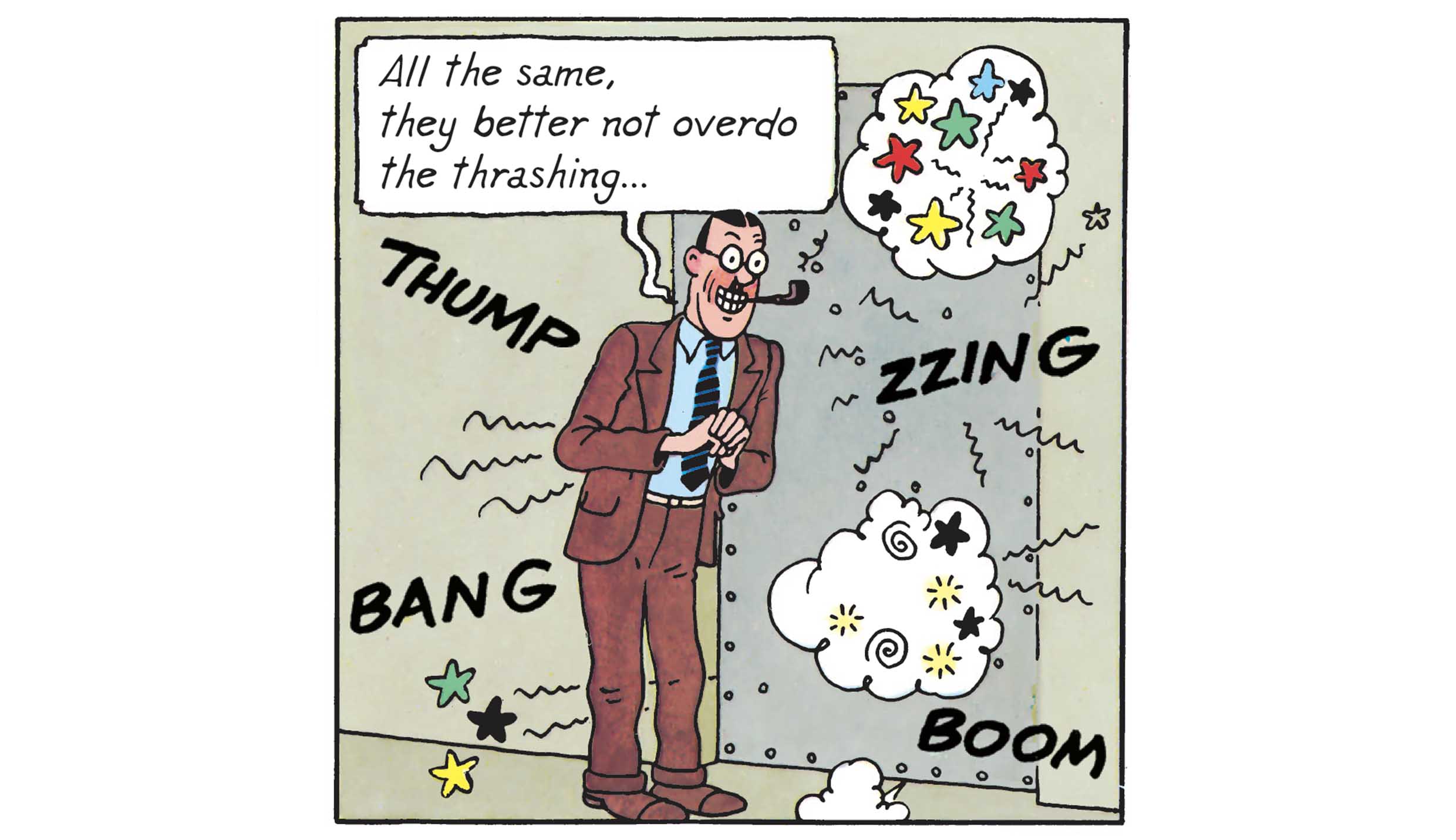

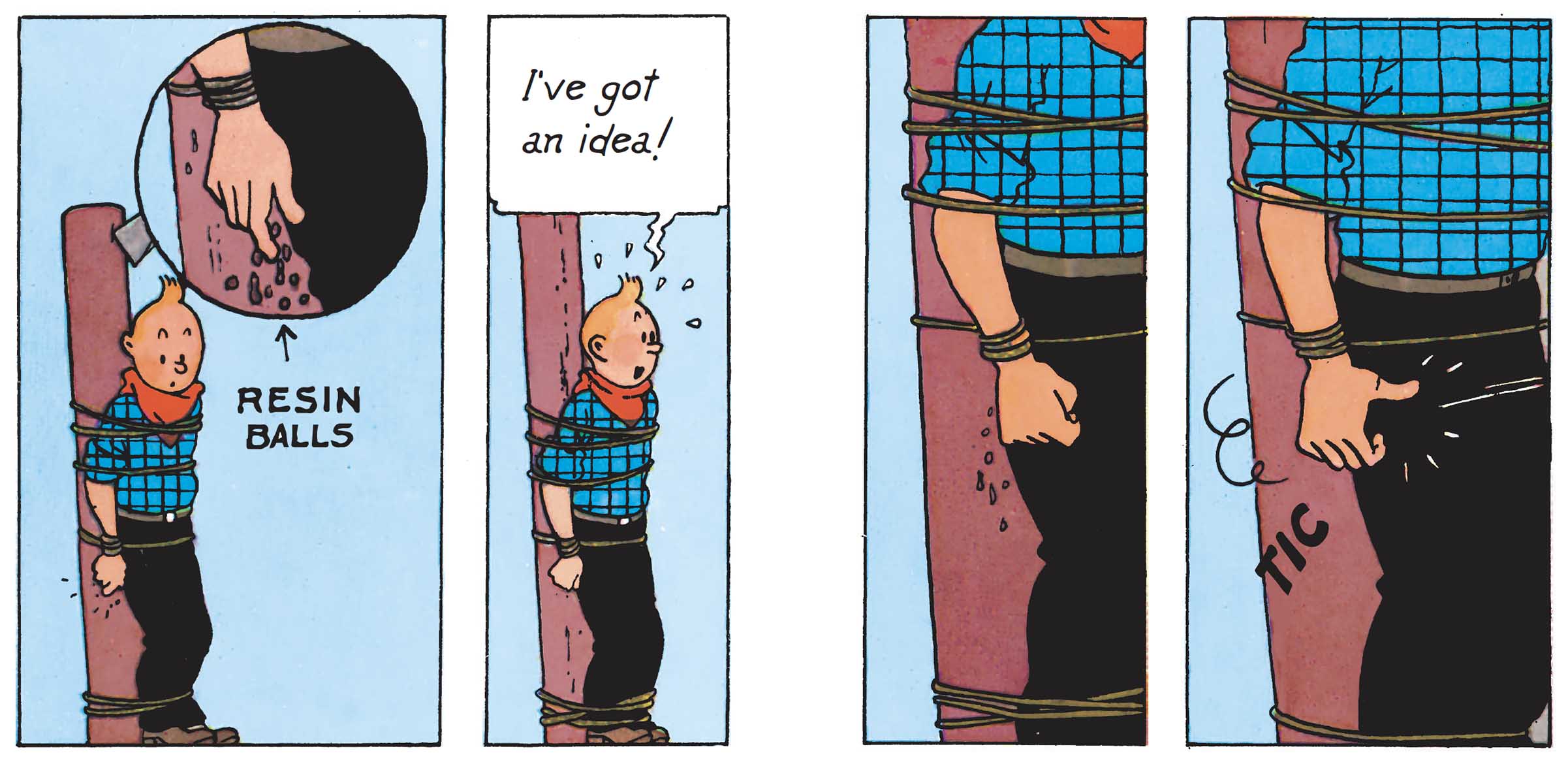

Our intrepid hero is often caught off guard, struck hard and clean from behind, often on the head, usually by cowards he meets along the way. He staggers, faints, and wakes up in the worst imaginable situations. Fortunately, with Snowy never far, or thanks to some well-placed narrative trick from Hergé, he escapes with a few bruises and his life intact. Phew! Even when tied to a stake, at the mercy of duped locals, he manages to flip the situation masterfully. And as for stars swirling over his head, there’s no shortage of those. Wherever he goes, Tintin somehow finds himself in ever more hair-raising situations.

"I’ll write him a prescription. A severe one. One he’ll feel." (2)

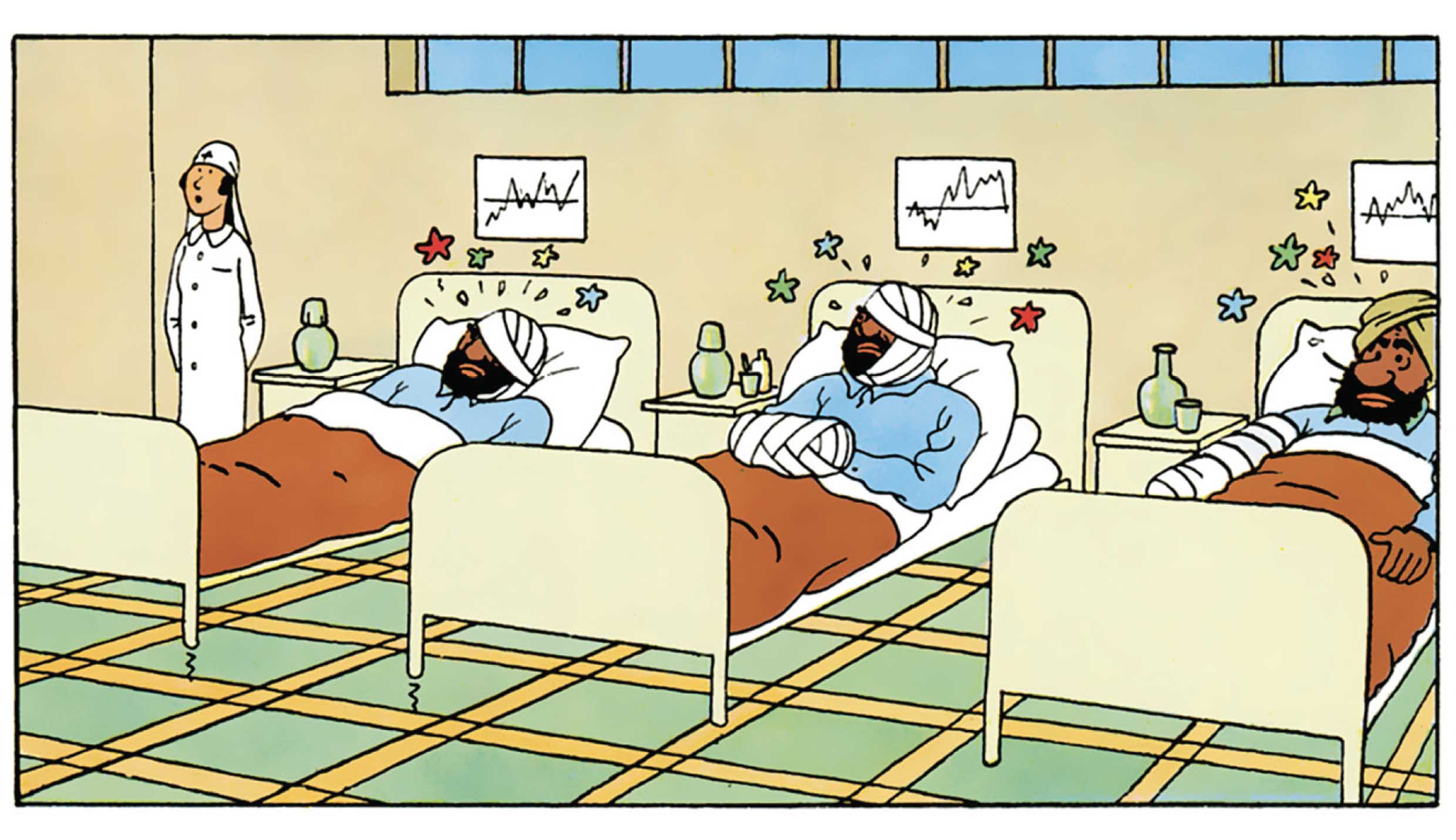

Hergé's storylines use fighting as an effective device: to trigger suspense, turn latent tension into open conflict, or punctuate the plot with a spectacular shift. In The Blue Lotus, Tintin takes on his foes alone, a one-on-one standoff with no outside interference. Small and seemingly fragile, he is ferocious when needed. Outnumbered, he counts on quality over quantity, sending a whole crew of hotheads to the hospital.

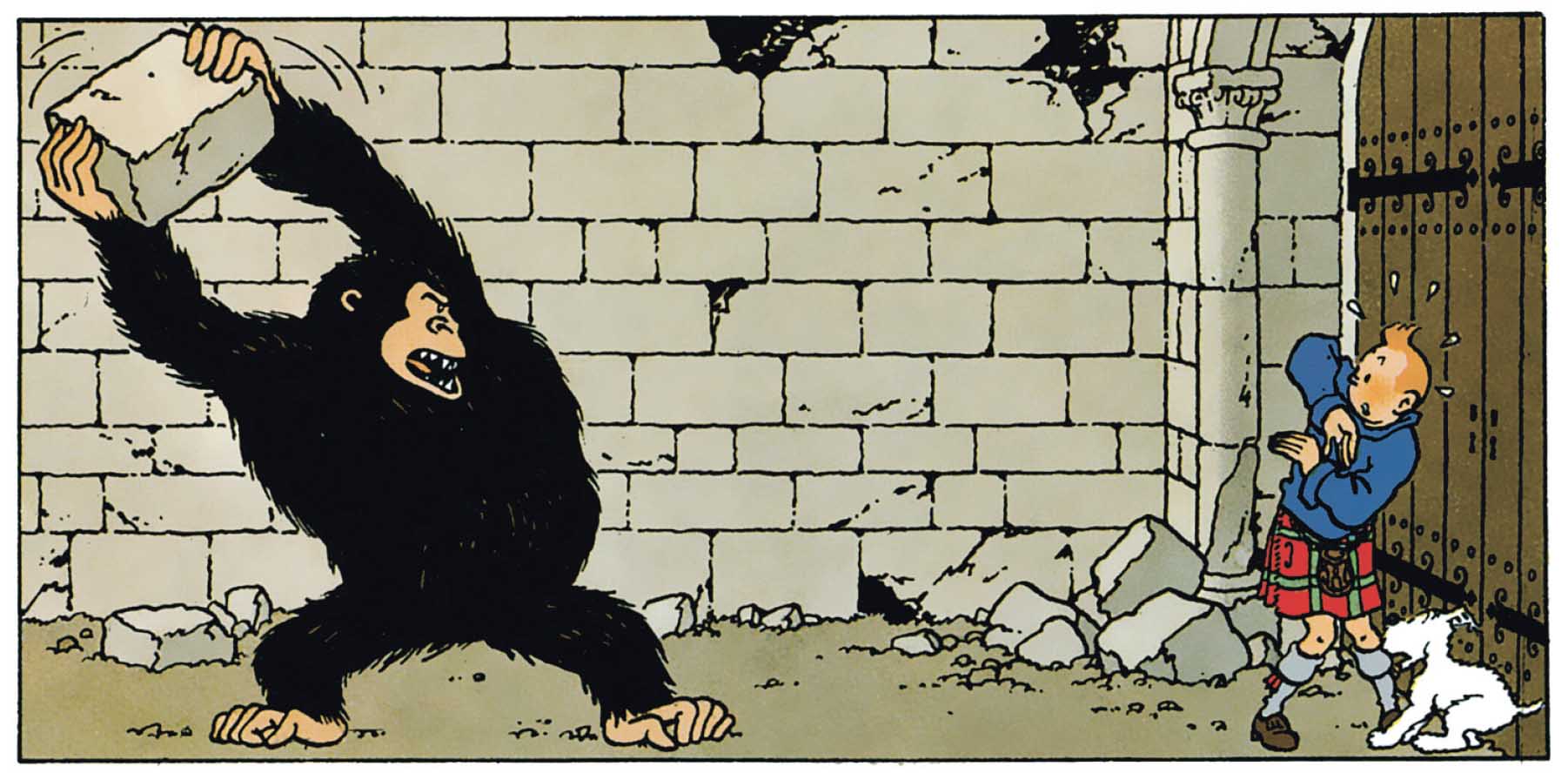

In The Black Island, Tintin faces a dark, hairy mass—the gorilla Ranko. He raises a stick, tiny in comparison to the beast, but it doesn’t work. He throws a rock. Still no use. Nothing works. Tintin, a wiry figure before a wall of muscle and rage, steps back, trembles, searches for a way out. No dialogue, no escape—just an absurd, unbalanced face-off. A clever kid versus a mountain. And yet, he holds firm. He doesn’t give in.

"I like guns... when I’m the one holding them!" (3)

Hergé applies the principles of the clear line to action scenes: no blur, no empty background, every gesture is crisp, every move easy to read. His visual style, drawn from silent slapstick cinema, gives violence a precise, almost choreographed quality: characters are shown in wide or medium shots depending on intensity, and the panel layout guides the action like a storyboard. And nothing is more cinematic than a weapon—gangsters and drug traffickers always carry them.

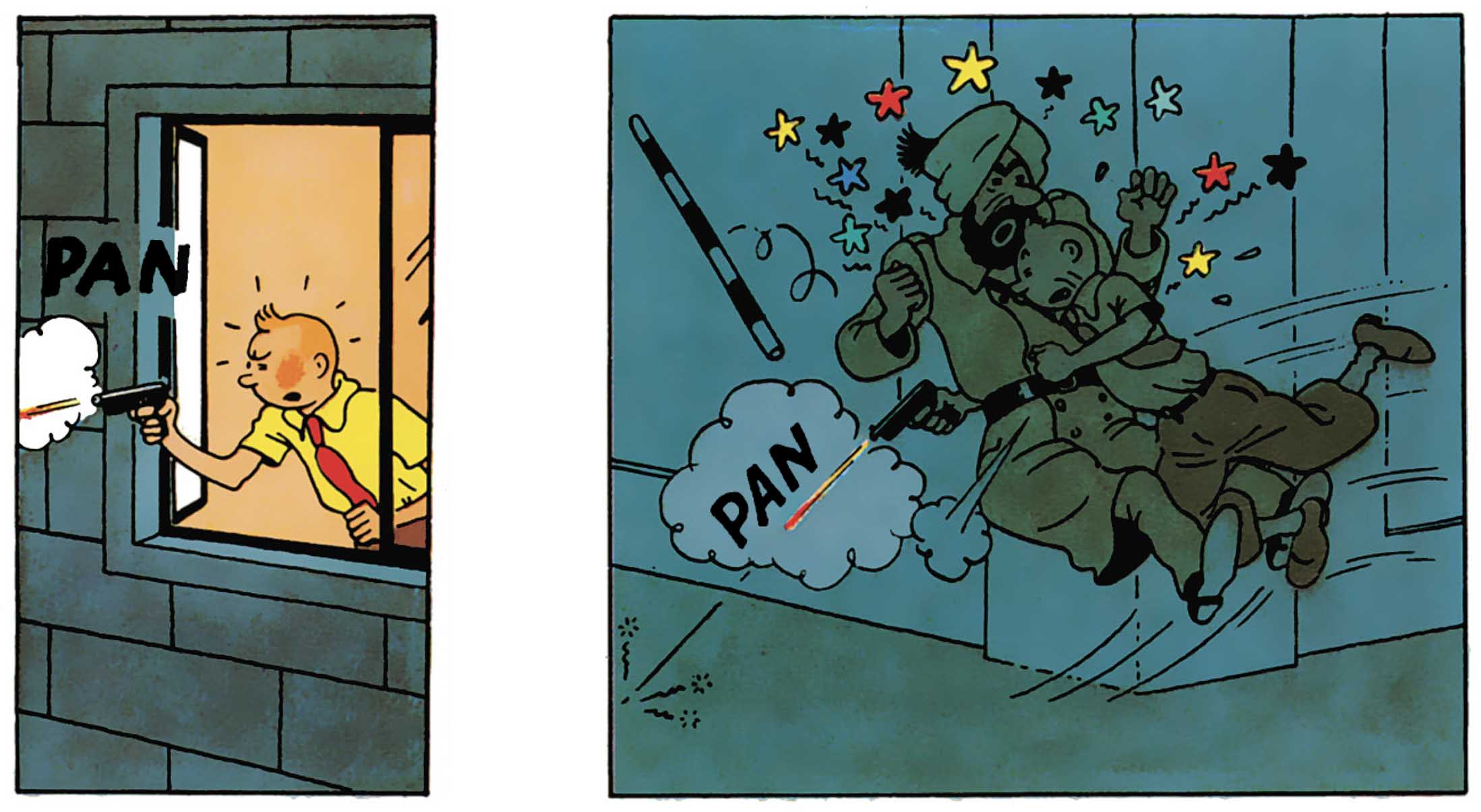

In Tintin in America, the stage is perfect, in the land of Calamity Jane and Davy Crockett. Spaghetti western vibes are never far in this revived Far West setting. On horseback, he charges forward and swiftly knocks out a thug. Under the scorching sun, in Incan lands, weapons clash with equal intensity. Every panel is meticulously composed, space used to build tension right before a confrontation. And when trying to stay out of sight in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, there’s no mistaking the whiff of gunpowder: Tintin has to take cover fast.

"When it’s too much, I blow it up. I scatter. I ventilate." (4)

Fights don’t just move bodies, they turn them into comic tools: Haddock’s colorful insults, the clumsy pratfalls of Thomson and Thompson, dizzy spells more laughable than harmful with professor Calculus, and Tintin twisting every which way to get out of trouble. If you squint, you can spot the influence of slapstick legends—Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd—in the way Tintin stretches, ducks, or dives to escape.

And just to top it off, Tintin is the master of dodging. In the thick of it, his agility is paired with a key sidekick: luck. So many fists and bullets whizz past his ear, missing by a hair. But let’s not downplay his merit either: Tintin has the grace of youth and defies every statistical odd stacked against him. No one’s been born yet who could take Tintin down a peg!

"No one hits harder than life" (5)

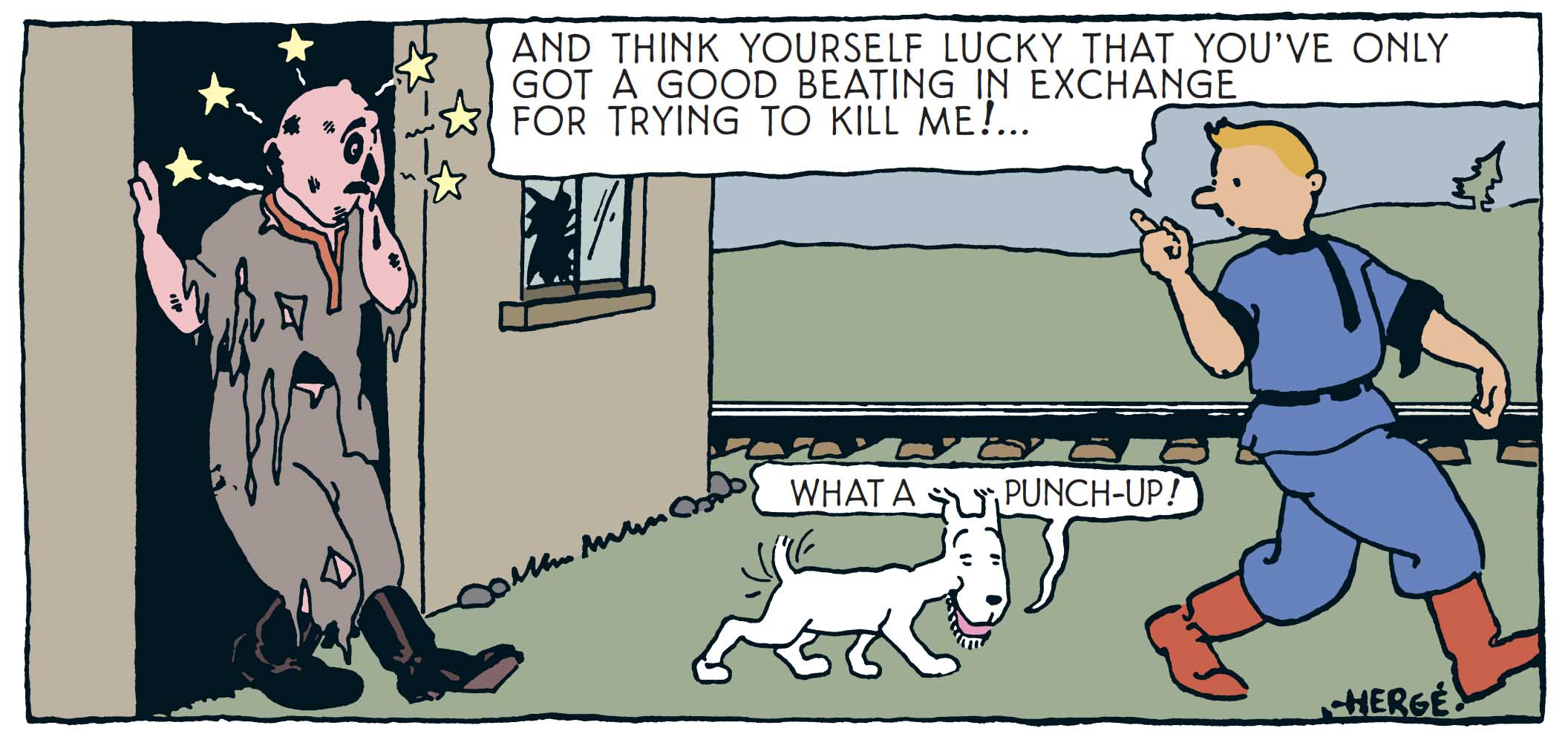

This parade of slaps, punches, wallops, and other merry whacks hides the bigger picture. Yes, the blows fly, but nothing bloody is ever shown. This restrained violence avoids gore: villains are punished, never executed. Tintin fights to serve justice, not to inflict gratuitous pain—a moral heroism free of cynicism.

In Tintin’s world, battles never show blood, and when deaths occur, they involve minor characters and are mentioned quietly. You never see a corpse after a brawl gone wrong. There are a few rare exceptions, like the almost-explicit death of two men, in a nearly theatrical staging, complete with grinning winged demons.

"Some random guys sticking their noses in? Come on, let’s not get angry!" (6)

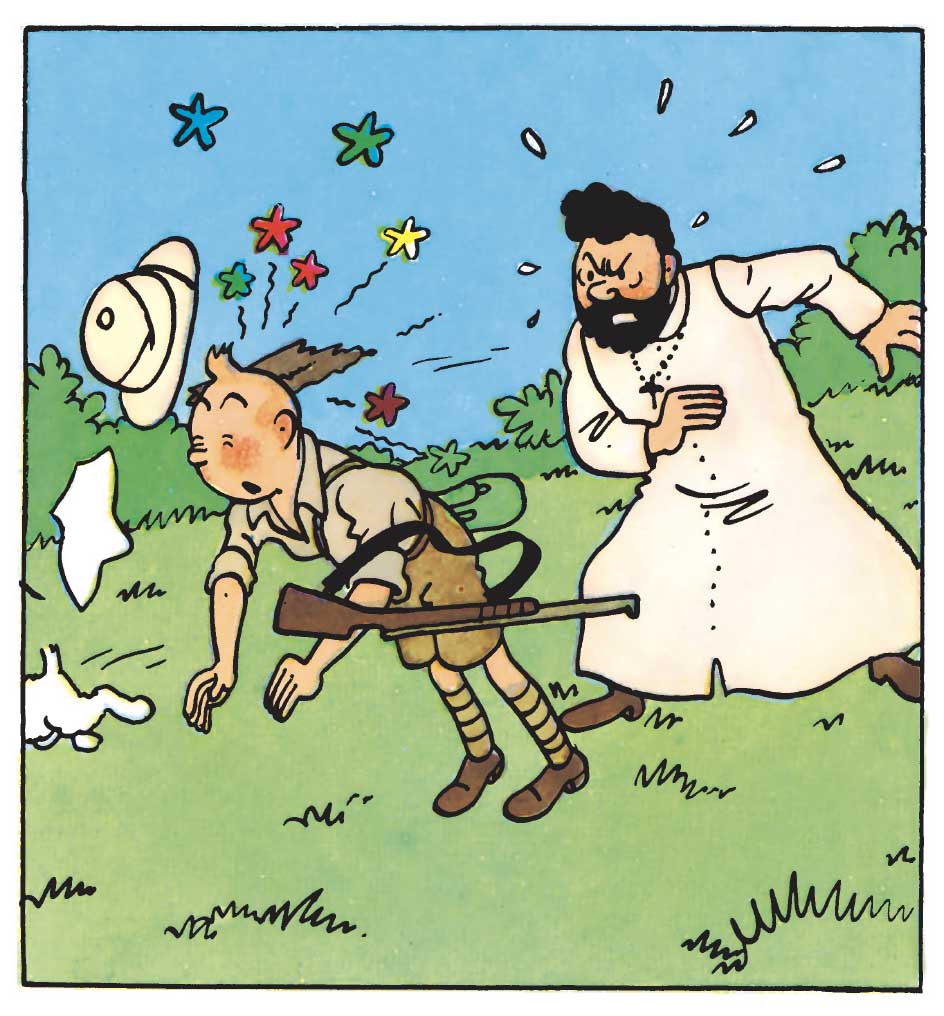

Is Tintin a good fighter? In The Blue Lotus, he takes out troublemakers with a good kick. In Prisoners of the Sun, he takes down a pursuer with a well-aimed rifle butt. And in Tintin in the Congo, he tumbles from a great height after a memorable scuffle. The scenarios vary and are almost always a bit comical.

We’ve seen his weak moments, sure, but also his feats and skills, luck aside. Confrontation reveals character: Haddock, rough and impulsive, lashes out spontaneously; the Thom(p)sons, clumsy, trigger fights more from incompetence than malice.

Tintin, meanwhile, stays composed, resolute, even when facing armed or dangerous foes—true to Hergé’s idealized vision of the noble son-reporter: intelligent, brave, morally driven.

Hergé constructs action scenes like a filmmaker: using powerful ellipses, dynamic camera-like angles, and graphic rhythm to amplify suspense and momentum. Like a visual tracking shot, each fragmented motion becomes a frozen, intense beat.

"I’m not knocking the slapstick, but fair play... we might have something to say." (7)

The earliest fights are rougher, chaotic tangles reflecting a young cartoonist still honing his craft. Gradually, they become more refined: every blow is anticipated, every reaction carefully drawn. This evolution mirrors the growing sophistication of Hergé’s graphic style and his rising artistic demands, down to the consistent thickness of each line.

Fights become less frequent over time; punch-ups almost disappear by the later albums. Tintin doesn’t age—but Hergé does. Perhaps with time, the wild escapades mellowed, softening the impetuous energy he once gave the young reporter. Times were changing, and the same momentum no longer applied.

Compared to other major comics where brawls are zany and festive, Tintin presents a tamer kind of violence, more in service of the story than as a comedic spectacle. Hergé’s violence is sharp, light, almost ritualistic—a narrative turning point. The contrast highlights Tintin’s distinct tone: an educated adventure, never base.

Violence is never the solution.

Deeply influenced by slapstick, Hergé aimed for a kind of violence accessible to children: never traumatic, yet perfectly capable of pushing the plot forward. Modern critics point out the absence of graphic or explicit death, noting how Hergé prefers the villain’s escape to his destruction. Fights in Tintin are neither heroic nor savage; more often, they’re amusing.

A storytelling tool with rhythmic flair, this violence is a carefully crafted graphic gesture. It lands with a dry thud in the blank space between two panels. It softens tension, propels the story, reveals character, entertains, but always stays within the bounds of light morality and crisp aesthetics. And on top of that, they can sometimes be quite original.

References for quotations used as titles:

- (1), (2), (3) et (4) – Les Tontons flingueurs (Crooks in Clover) (1963)

- (5) – Rocky Balboa (2006)

- (6) et (7) – Ne nous fâchons pas (Let's Not Get Angry ) (1966)

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books