Rascar Capac: The Fantastic in Hergé’s Work

With The Seven Crystal Balls, the author plunges us into an atmosphere of dread that has haunted generations of readers. That collective shiver takes shape in the figure of Rascar Capac, the unsettling mummy brought back from an Inca expedition, whose shadow looms over the entire album.

Here, Hergé signs one of his most fantastic stories, in the literary sense, a world at the frontier between dream and reality, where doubt and unease mingle with adventure. The tale, steeped in archaeological echoes and real-world legends, touches on themes of desecration, curse, and the sacred. So, wrap yourself in a warm blanket by the flickering light of candles, for today we lift the veil on the fantastic side of Hergé!

A gloomy prelude

Created by Hergé and introduced in The Seven Crystal Balls, Rascar Capac is an Inca emperor whose mummy becomes the centerpiece of what is often described as one of the most frightening stories in the series. His name appears as early as the first page, through a newspaper article recounting the Sanders-Handiman expedition’s return from Peru with his remains, still crowned with the royal borla, a golden diadem. Brrr, that sets the tone.

Though the eerie artifact rests safely behind glass in Professor Hippolyte Tarragon’s home, it comes with a prophecy foretelling a curse upon the desecrators. « Imagine if someone did the same to our own kings! » remarks a fellow passenger near Tintin. Indeed, a chilling thought…

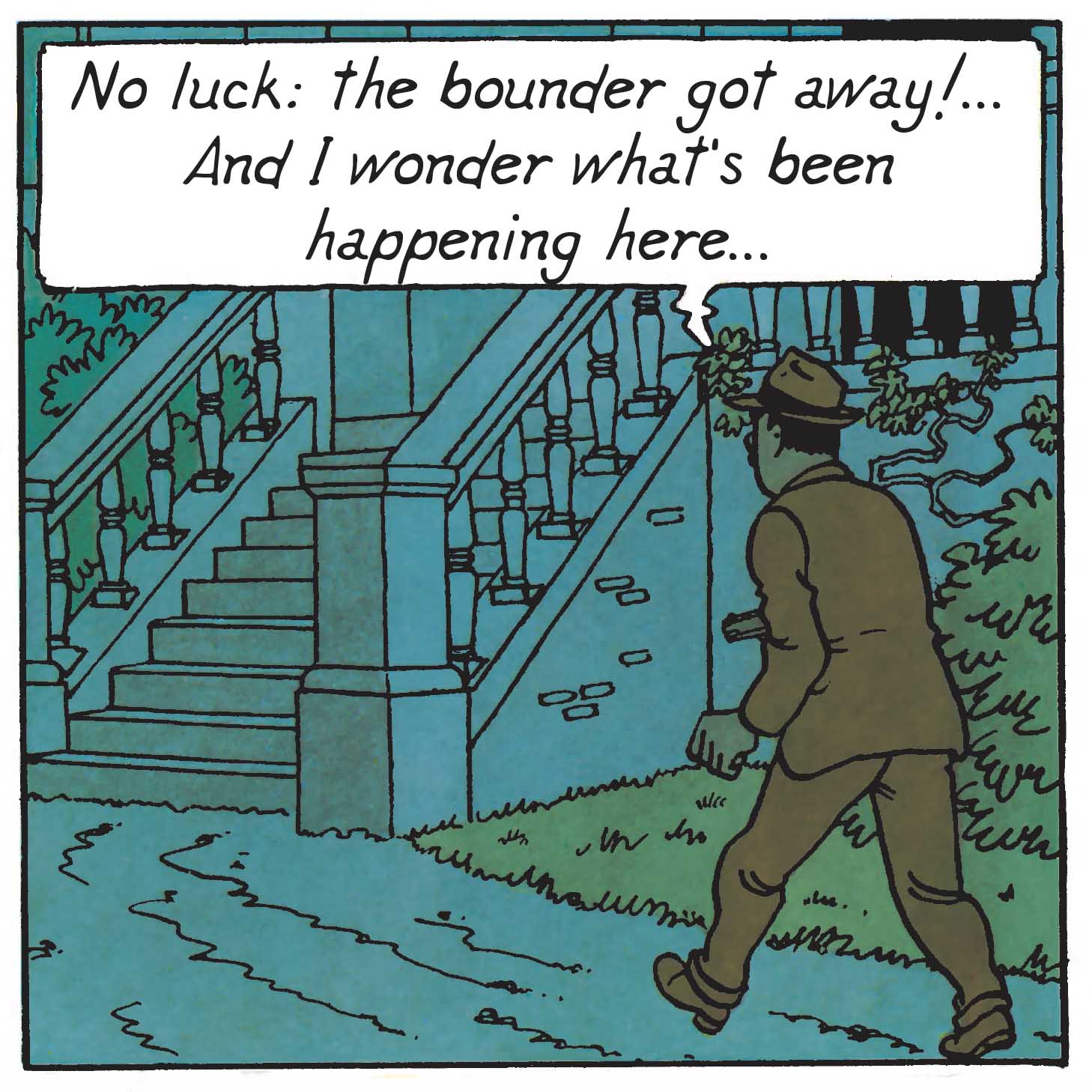

When the mummy suddenly vanishes in a burst of ball lightning, then intrudes into Tintin’s room that same night, a continuous tension grips the story. Though he appears in only a few panels, Rascar Capac permeates the album and collective memory, inspiring later artists and sparking real-world controversies well beyond the pages of the comic. A hair-raising tale, enough to make one drop a monocle… Let’s hope Captain Haddock has a spare!

At the heart of the story

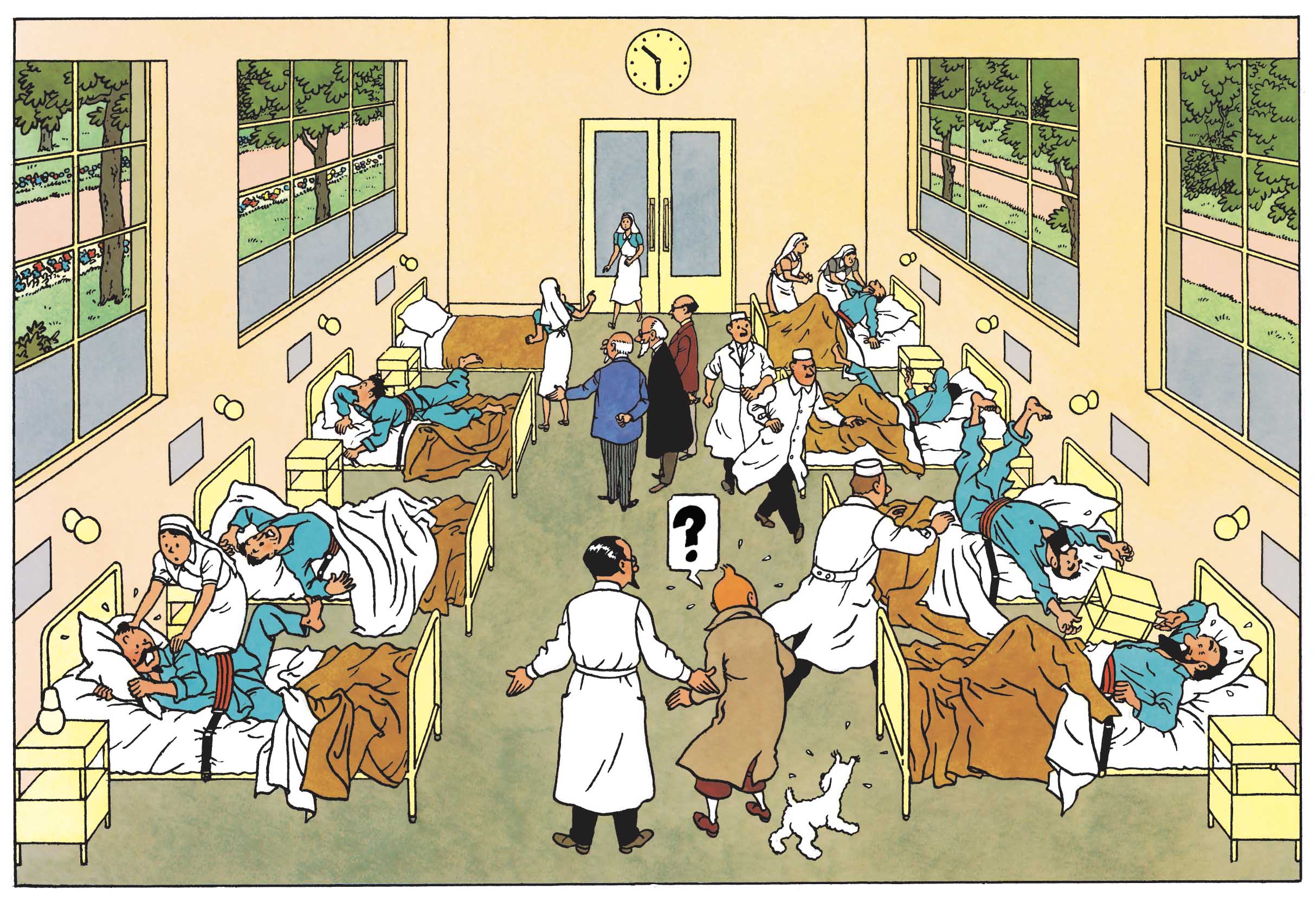

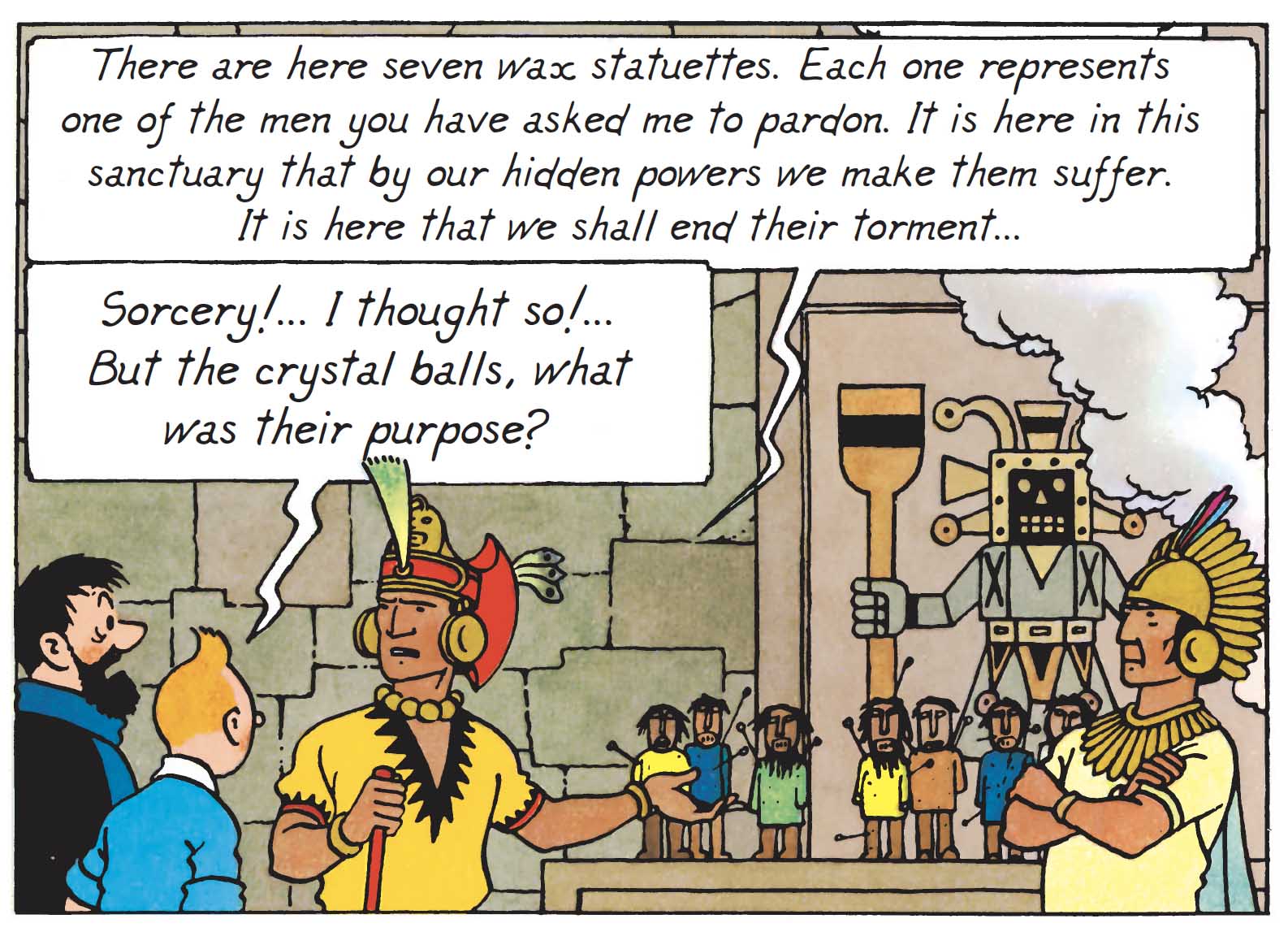

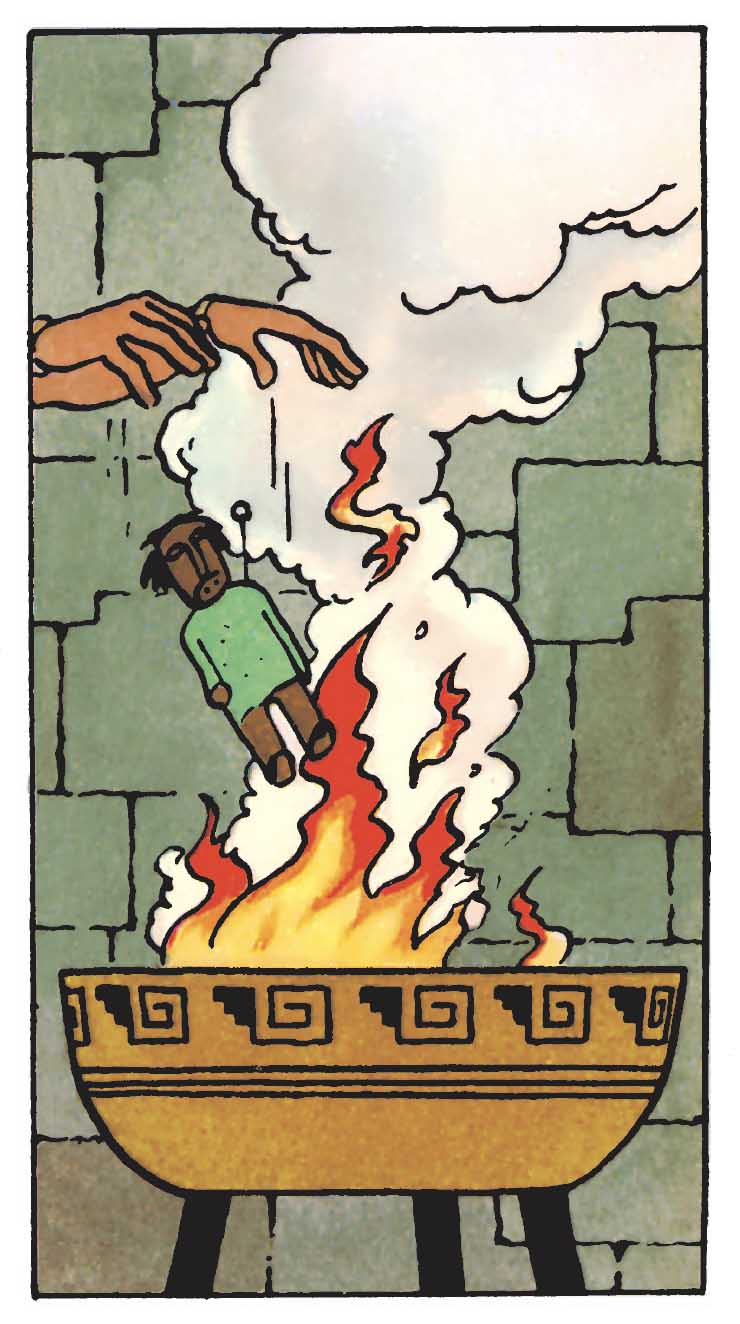

The narrative machinery unfolds early: the mummy, taken from an Inca tomb, is displayed at Tarragon’s home. But things quickly spiral into panic. One by one, the members of the expedition fall into deep lethargy, each found beside shattered crystal fragments.

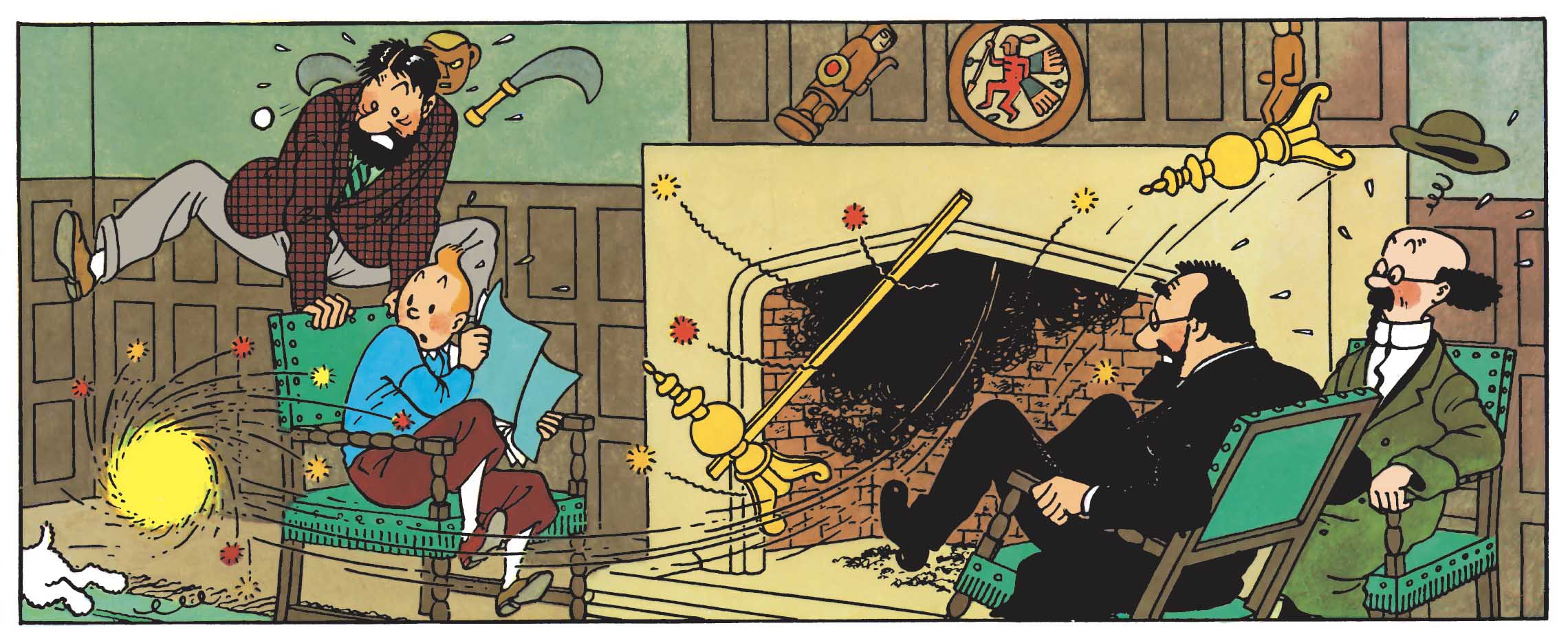

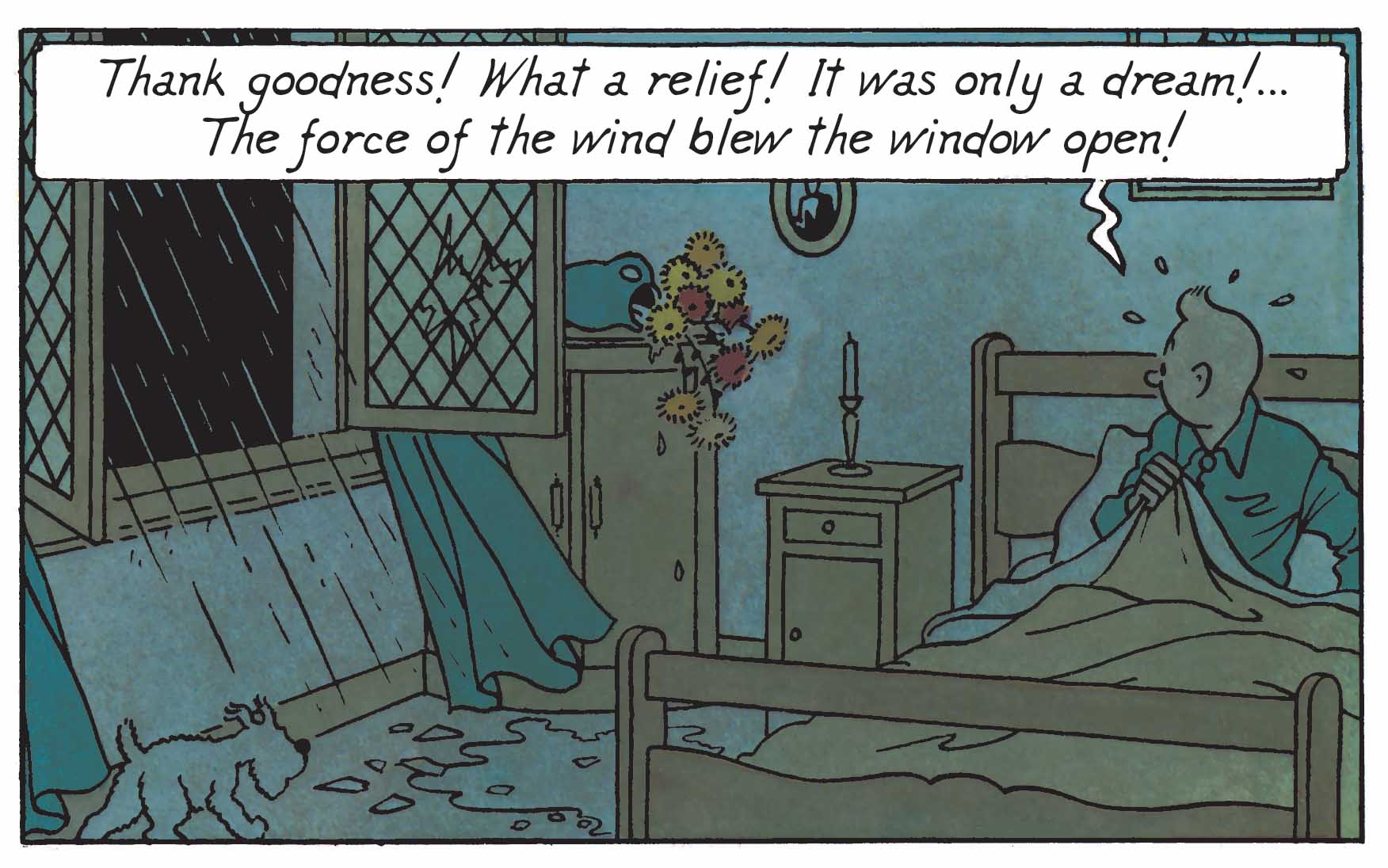

As the investigation stalls, bam! a thunderstorm breaks, and a bolt of ball lightning sweeps through the chimney. The preserved body vanishes, leaving behind only its jewels. Tarragon then realizes that the prophecy is coming true. That night, Rascar Capac appears in the dreams of Tintin, Haddock, and Calculus. The next morning, after putting on the mummy’s bracelet he found in the garden, Professor Calculus is kidnapped, setting the stage for the sequel.

Brief though it may be, Rascar Capac’s presence is decisive, a true vector of the fantastic, unlike anything seen before in Hergé’s work. His very elusiveness amplifies his symbolic power: the Inca quite literally haunts the album. Hergé masterfully cultivates the reader’s hesitation: nothing proves it’s merely a dream, and no clue clarifies the boundary between illusion and reality. Even the open window radiates a quiet menace the reader instinctively feels.

From Andean mummies to European imagery

Let’s catch our breath and try to rationalize. The visual genesis of Rascar Capac draws from several iconographic sources. Some research points to the influence of a 19th-century Andean mummy, today displayed in Brussels, whose crouched posture and hands clasping the head closely resemble Hergé’s drawing (cf. RTBF article - in French only)

Other studies suggest that a Larousse du XXe siècle engraving served as the direct model, matching the mummy in the comic almost exactly, particularly in the presence of bindings absent from the Brussels specimen.

The mummy’s pose in its glass case has even been compared to the gesture of the figure in Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Readers can judge for themselves this curious resemblance… Likewise, the expressive faces and bound forms of certain Chachapoya mummies have left a mark on European imagination. Finally, the ball lightning scene reflects scientific and popular imagery of the 19th and 20th centuries, a spectacular yet plausible trick allowing Hergé to make the body « disappear » without immediately dispelling the mystery. The magician Hergé strikes again!

The curse itself revives a familiar topos: the desecrated tomb and divine punishment, a motif popularized after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Hergé had already explored it in Cigars of the Pharaoh. Here, it’s woven in from the first page through the newspaper and later the inscriptions translated by Tarragon.

A long-reaching tale

Let’s replay the scene for a moment: the Inca appears rarely, yet night and storm wrap everything in menace. Scattered objects, the crystal balls, Calculus’s recovered bracelet, weave the story’s web of mystery.

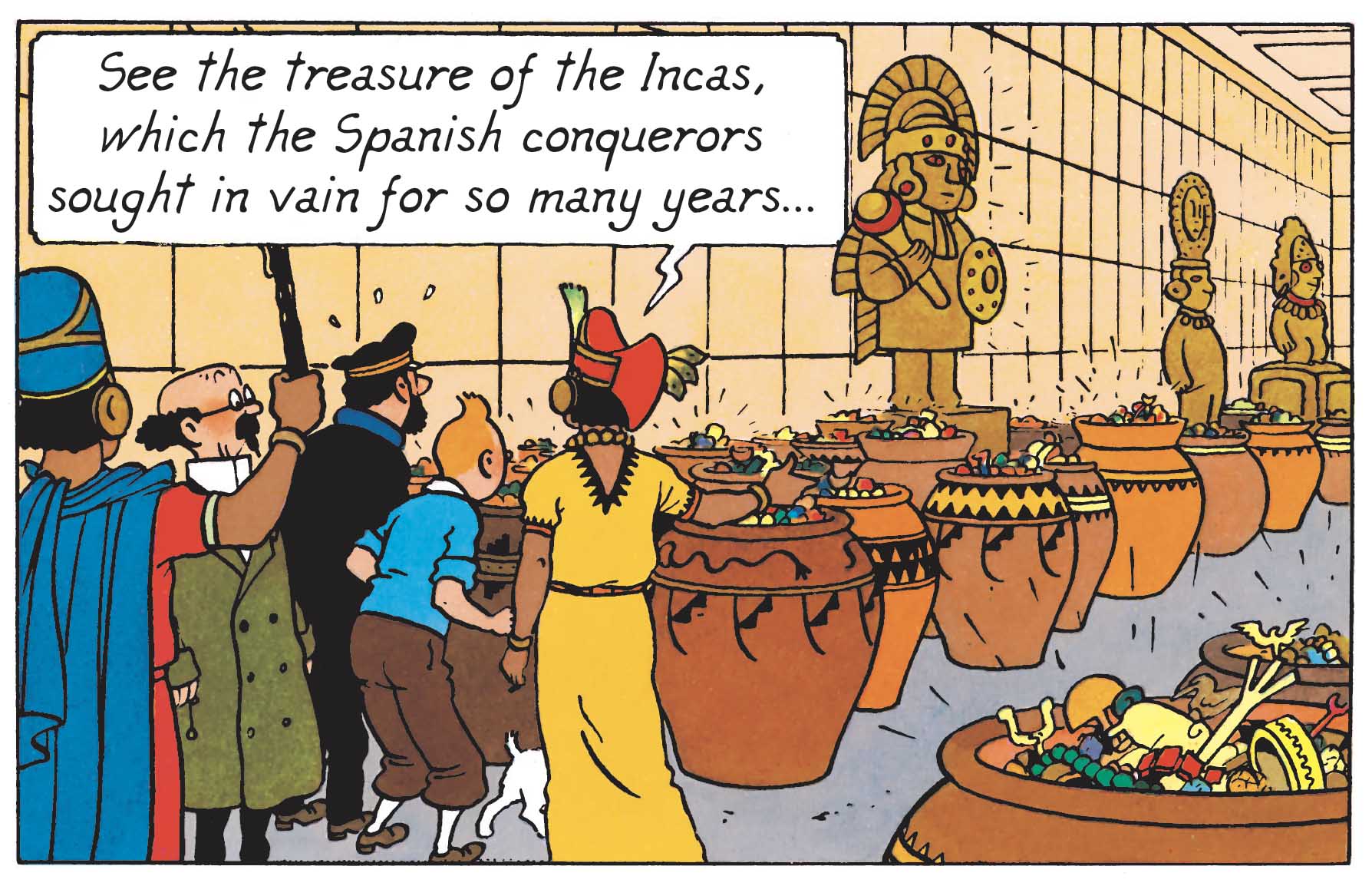

At its center: the display case that « museifies » the sacred before it comes alive again; the window as threshold between exterior and interior, life and death. Many readings highlight the opposition between two worlds, the Inca sacred order, where the mummy is an object of veneration, and the European profane order, governed by science and rationalism.

A reminder of reality within the fantastic? The violation of the tomb upsets Andean balance; the vengeance of the prophecy becomes the instrument of reintegration, though at the cost of collective punishment. Tarragon’s skepticism embodies Europe’s deafness to indigenous beliefs; his fall into lethargy marks the forced return of the sacred into the profane world. In this light, Rascar Capac is not merely a monster, he embodies the sacred’s power to reclaim its due. And in Prisoners of the Sun, the circle closes: the explorers are freed from their curse once the sacred order is restored, sealing the reconciliation of both worlds.

A paradoxical vision

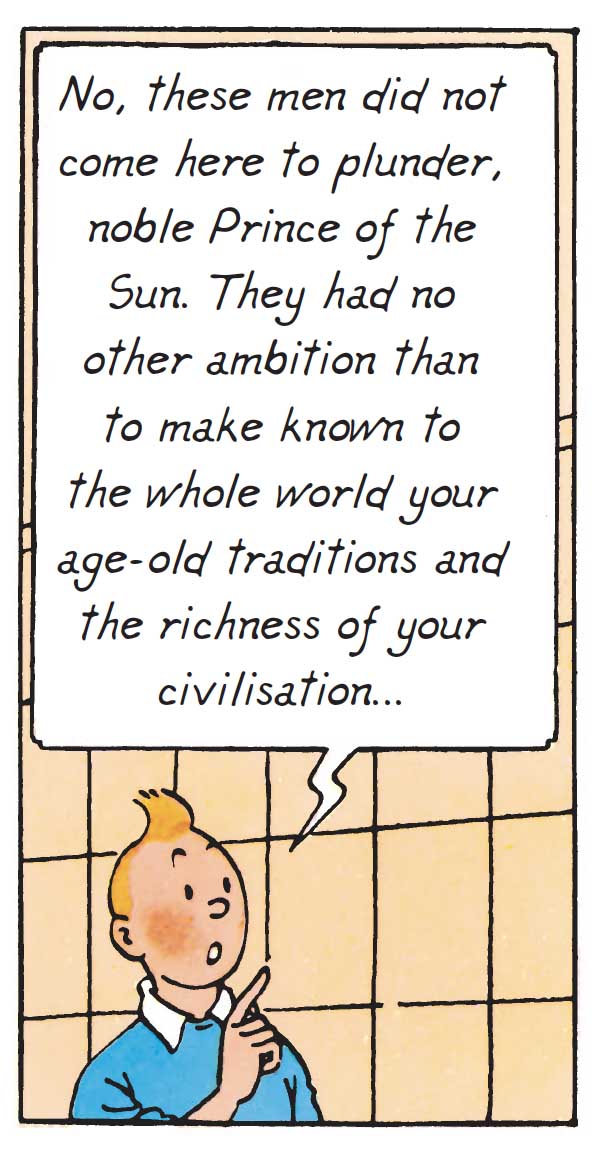

As mentioned earlier, the album stages an explicit critique of spoliation (the traveler in the train wonders, « What would we say if…? ») while giving form to a fear of the foreign, the mysterious « illness, » the Inca’s threat on European soil. Hergé thus appears ambivalent: he legitimizes vengeance against the looters yet portrays that otherness as dangerous to Europeans. Later in the diptych (cf. Prisoners of the Sun), Tintin defends the idea that the scientists merely sought to reveal “the splendor” of a lost civilization, a position that highlights Hergé’s nuance within his work.

This ambiguity fuels the richness of interpretation: the curse may symbolize the disorder brought by violent cultural encounters, yet the story never abandons its adventurous drive. Such exotic epics are a hallmark of Hergé’s art, part mystery, part comedy, part quest for understanding other civilizations.

Indeed, the fantastic is not confined to this album. If the supernatural and fear never again reached such intensity as in The Seven Crystal Balls, they nonetheless hover elsewhere, teasing the European rational mind. In The Black Island, the isolated castle and its “monster” evoke Gothic tales; in The Secret of the Unicorn, the ghostly treasure recalls the dread of the past; and in Tintin in Tibet, the Yeti stands at the threshold of myth and reality. These echoes show how Hergé, without abandoning adventure, continually summons the uncanny and the invisible, making readers shiver to this day. Even in 2025, we still tremble at the sight of that emaciated, uncontrollable face.

Memory, tributes, and legacy

Rascar Capac’s mummy far surpasses the confines of a single album. The character has haunted « several generations » of readers, often cited as a childhood nightmare. His legacy endures through countless homages and adaptations: Jacques Tardi’s nods (up to revived mummies in Adèle Blanc-Sec), a 2019 documentary investigating the « real » model, and even a 2020 controversy when a Belgian zoo exhibited a mummy it wrongly claimed had inspired Hergé. The figure even lives on in popular music, where it has served as an artist’s alias.

Up to Prisoners of the Sun, one might almost see in it the echo of Hiram Bingham’s adventure, who in 1911 rediscovered Machu Picchu in Peru, a site then unknown to the Western world and filled with mysteries and gold… with Tintin’s keen sense in place of Bingham’s flaws.

These afterlives confirm the character’s iconic power: in just a few scenes, Hergé created an emblematic image that haunts the collective imagination, linking us to archaeology, history, and a shared human curiosity. Yet behind this fascination with the distant, it is the fleeting touch of the fantastique that watches over them all.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books