Enchanting... in song

Let's continue our incursion into the musical world of The Adventures of Tintin, this time discovering the hits sung by our favourite heroes.

As we saw in the previous dossier, Hergé used music throughout his work to add sound to his pictorial stories. Of course, in addition to instrumental parts, songs are also used. But the lyrics have to fit the tone of the story. Fortunately, the repertoire in this area is rich and varied. So rich and varied, in fact, that Hergé has drawn from it the best titles - those that ring true to his paper opera.

So, are you ready for this well-constructed singing tour?

"Take care of your entrances, take care of your exits..."

“... and in the middle, do your job”. Maurice Chevalier's advice to Johnny Hallyday at the start of his career. Something that Hergé, too, has always intuitively applied. Particularly when he called on a song to sublimate his introductions. Proof that, as well as being a fine mind, he was also gifted with an innate sense of showmanship and stagecraft.

In Broken Ear, for example, when “The Toreador Song/March” intrudes in the opening vignettes, it is of course to accompany the museum guard's daily routine, but also and above all, to set in motion the “drama” that will later be played out. For if “Fond eyes gaze" look at the good man, it's not so much the eye of the statue in the foreground as the one that - by belief or superstition - is described as: evil. “It's witchcraft”, he confirms, when, in the space of just a few frames, he witnesses the disappearance, then spontaneous reappearance, of a curious fetish.

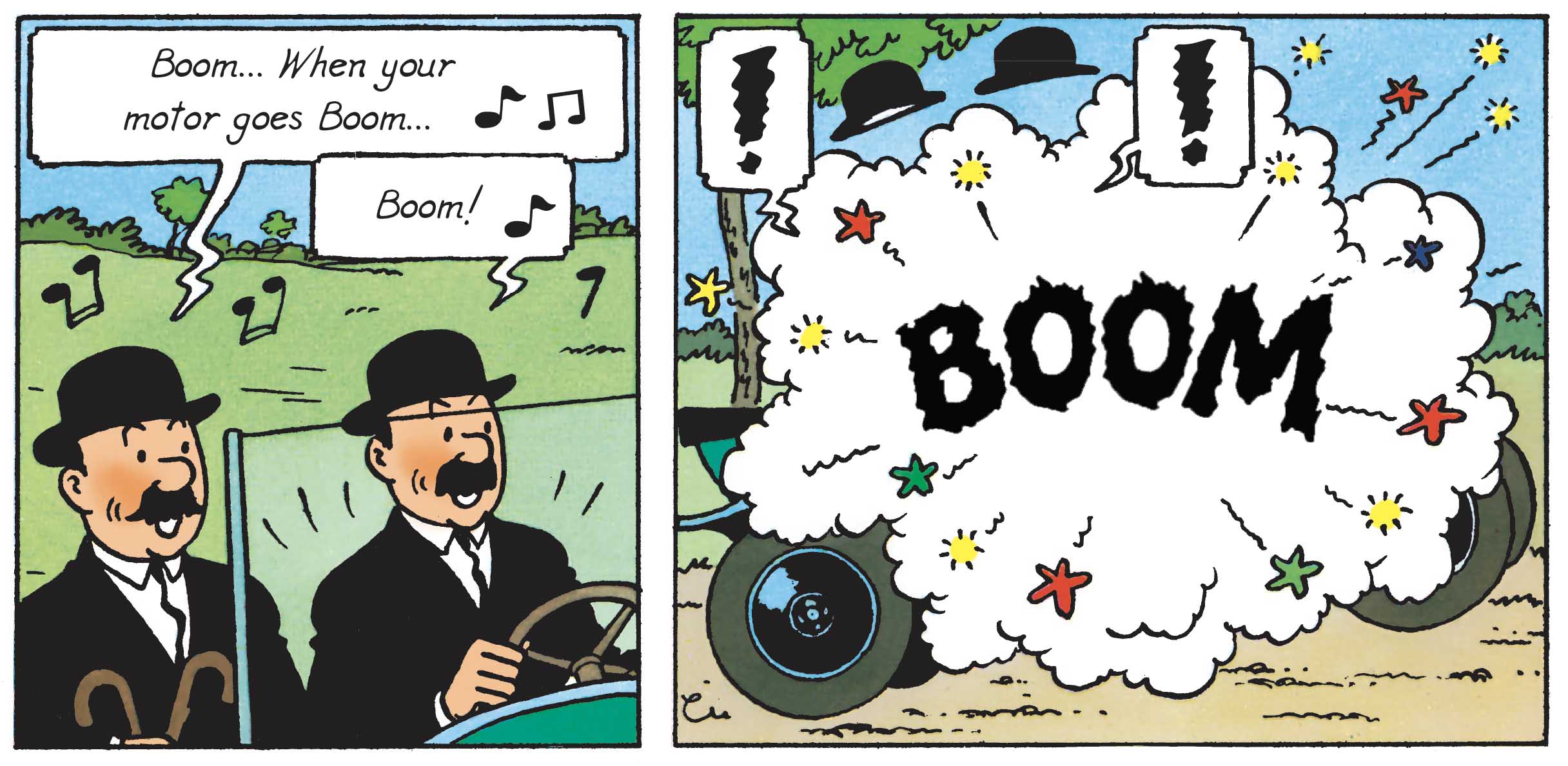

Even more significant is the Thom(p)son's grand opening in the Land of Black Gold. Here, all the ingredients are in place for an astonishing... or rather, explosive opening scene: a gas pump, a lighter, a smoking exhaust pipe and, to top it all off, the famous Belgian police duo singing Charles Trenet's “Boum! There's no doubt about it, the investigation that follows is bound to be... explosive!

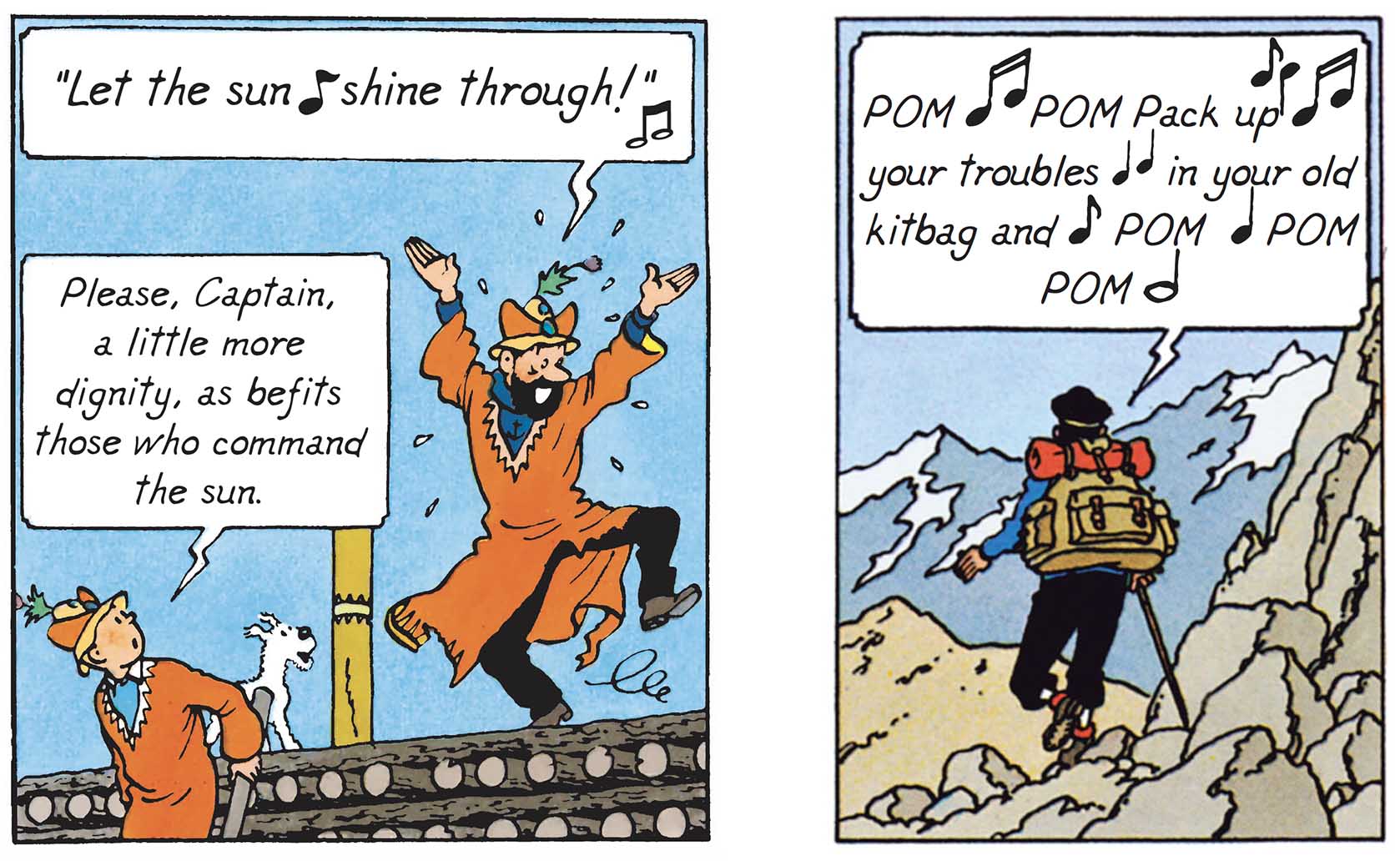

The musical trick also works very well as a denouement. Probably because the fall seems softer when it's skilfully orchestrated. That is why, in Prisoners of the Sun, Captain Haddock sings : “Let the sun shine through". A fitting title especially after a life-saving eclipse puts an end to the burning at the stake to which he and his friends were condemned. In Tintin in Tibet, he repeated the experience, in order to end on a high note but above all, on a note of lightness, in an adventure particularly rich in emotions. So he hums, not without a certain relief: ”Pack up your troubles in your old kit bag”.

Hymns of joy

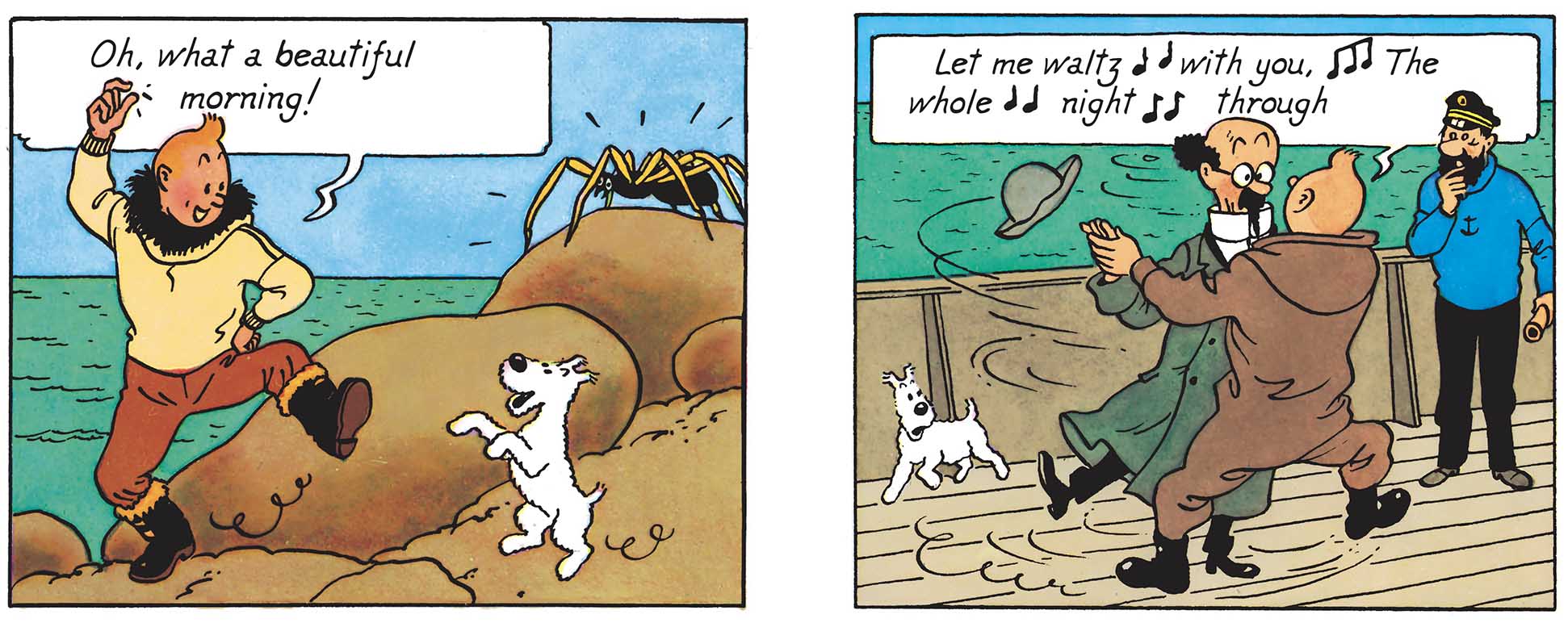

Used in the course of a story, after a moment of doubt or tension, songs also serve as an outlet. Singing is an excellent way for characters to release pressure. Especially if the outcome of the action is in their favour. In that case, they're pure expressions of jubilation. A vivid, authentic and spontaneous expression of their most intense emotions.

In addition to being odes to joy, these happy passages give a singular relief to their discoveries. For them, every advance counts. It's good news worth celebrating. It's proof that they're well on their way to solving their case. Tintin, in particular, seems to appreciate these moments of grace, since in The Shooting Star and Red Rackham’s Treasure, he himself is the initiator. For the occasion, he performs “Oh what a beautiful morning” and “Let me waltz with you”. It's worth noting that these scenes of jubilation are usually performed as a duo or trio, preferably on one foot.

It's impossible to talk about joy without mentioning “The Jolly Follies” song. This original creation - the pure fruit of Hergé's imagination - is, indeed, an invitation to party. An invitation no one can resist. Not even General Tapioca, for that matter. The dictator featured in Tintin and the Picaros quickly succumbs - very quickly, in fact - to its frenzied rhythms, right from when the very first stanzas are sung. Music really does soften the blow - and hearts, too.

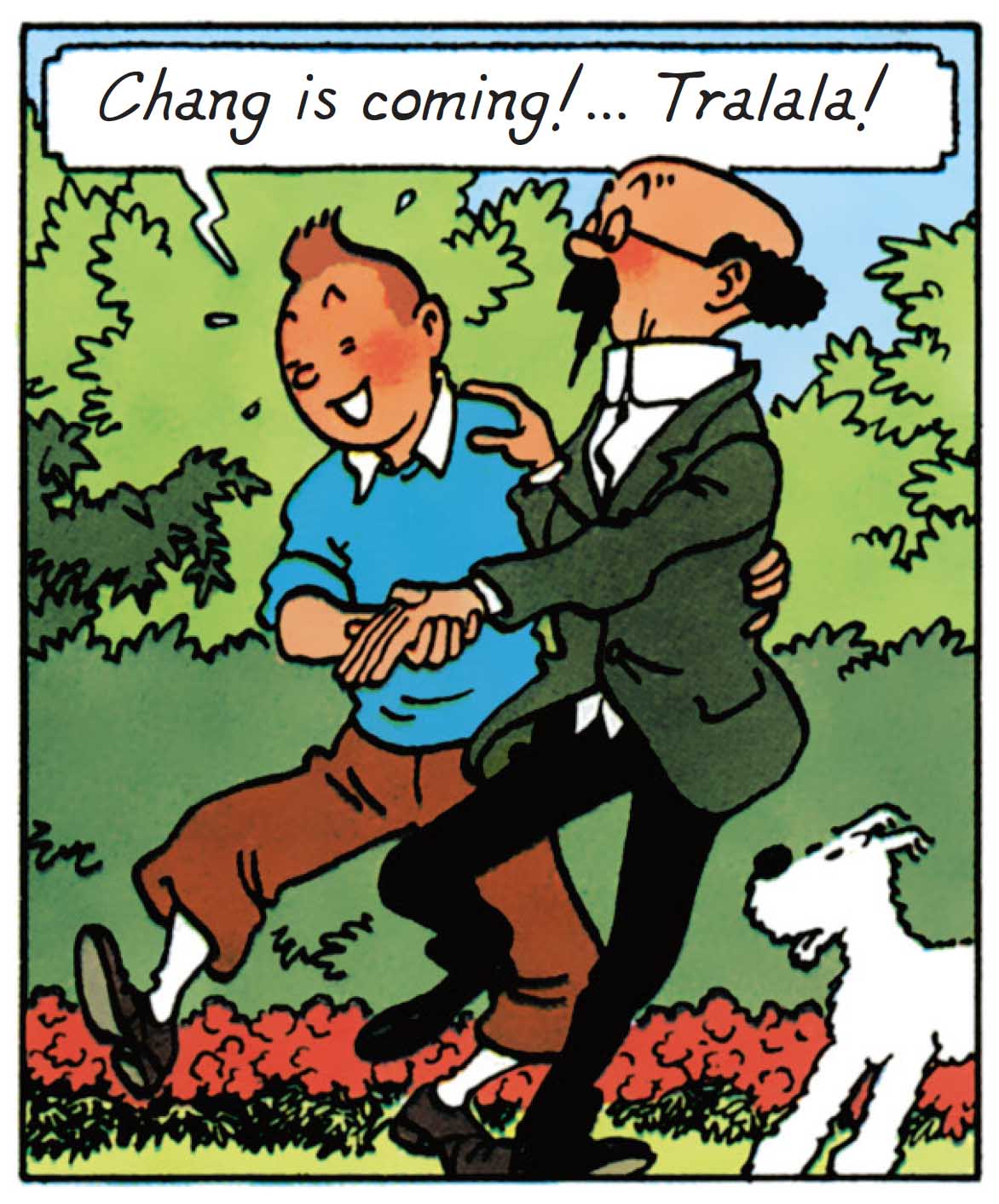

More neutral but just as effective - especially if accompanied by a jump or a dance step - the interjection “tralala” is also used on several occasions by Hergé's heroes, to express fleeting, rather bubbly and cheerful happiness. This is the case, for example, in Tintin in Tibet, when the young reporter rejoices at the imminent arrival of his friend Chang.

Of course, drunken merriment is also an excellent reason for music. But in this case, rather than drawing from the repertoire of drinking songs, Hergé prefers to accompany his heroes' drunkenness with songs that reflect their personalities. That's why, when he's inebriated, Haddock often sets sail from reality, singing intoxicating sea tunes such as “Drunken Sailor” or “A-Rovin”.

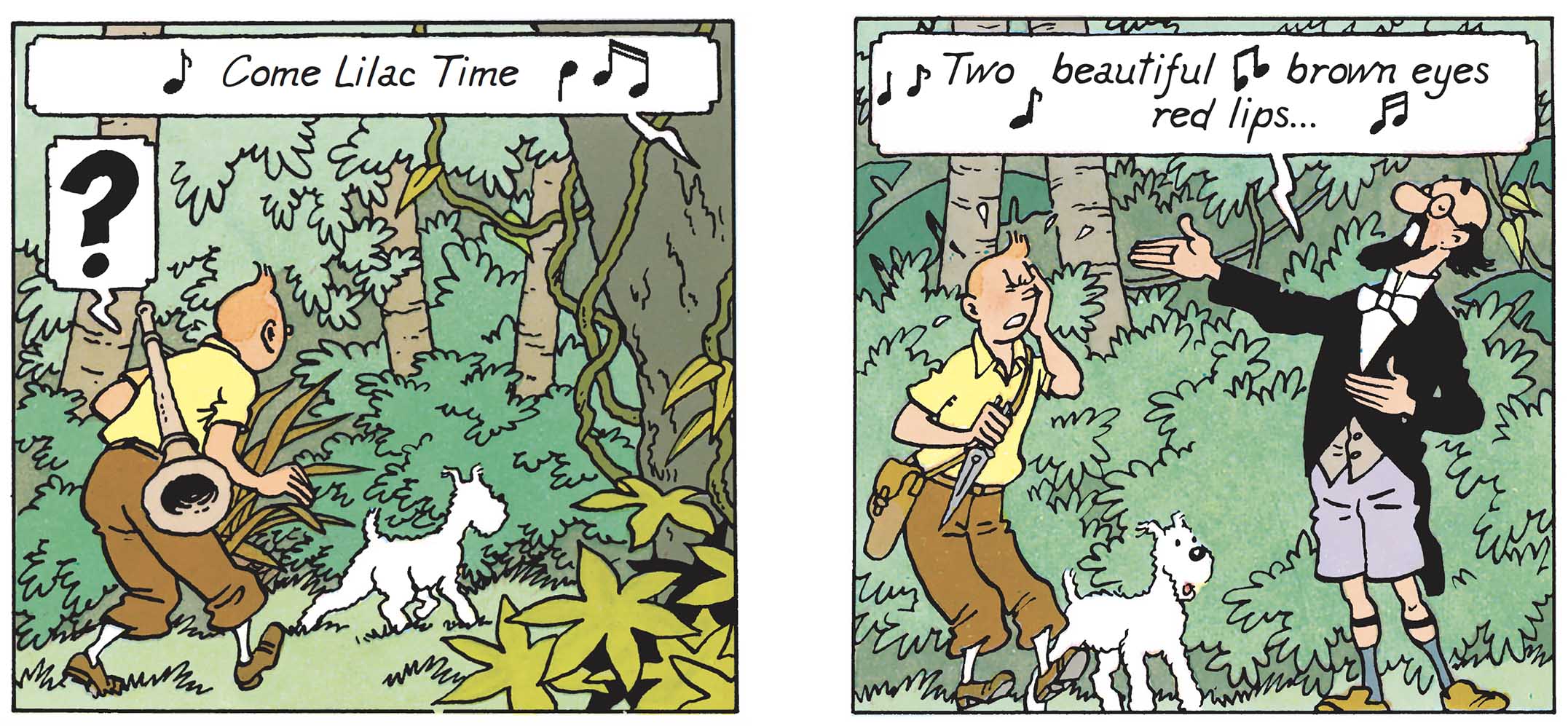

Finally, mild insanity also has its own register in which to express itself. Doctor Sarcophagus’ performance in Cigars of the Pharaoh is remarkable in this respect. After losing him in the tomb of Kih-Oskh, Tintin finds him, in India, in the forest, singing “The Sheik of Araby”. A few vignettes later, the unfortunate man's second attempt, is “Two lovely black eyes”. But this time, although the words seem delirious at this precise moment in the story, they are perfectly in tune with the situation. Tintin, like the reader, will confirm this in the following panels.

Songs of deed

When they don't directly support the storyline, the songs can also serve as a complement to the object or rather a direct, or even indirect, image. Indeed, Hergé uses them to give his readers additional clues, so that they can fully appreciate all the subtleties - including the impalpable ones - of the comic strip action.

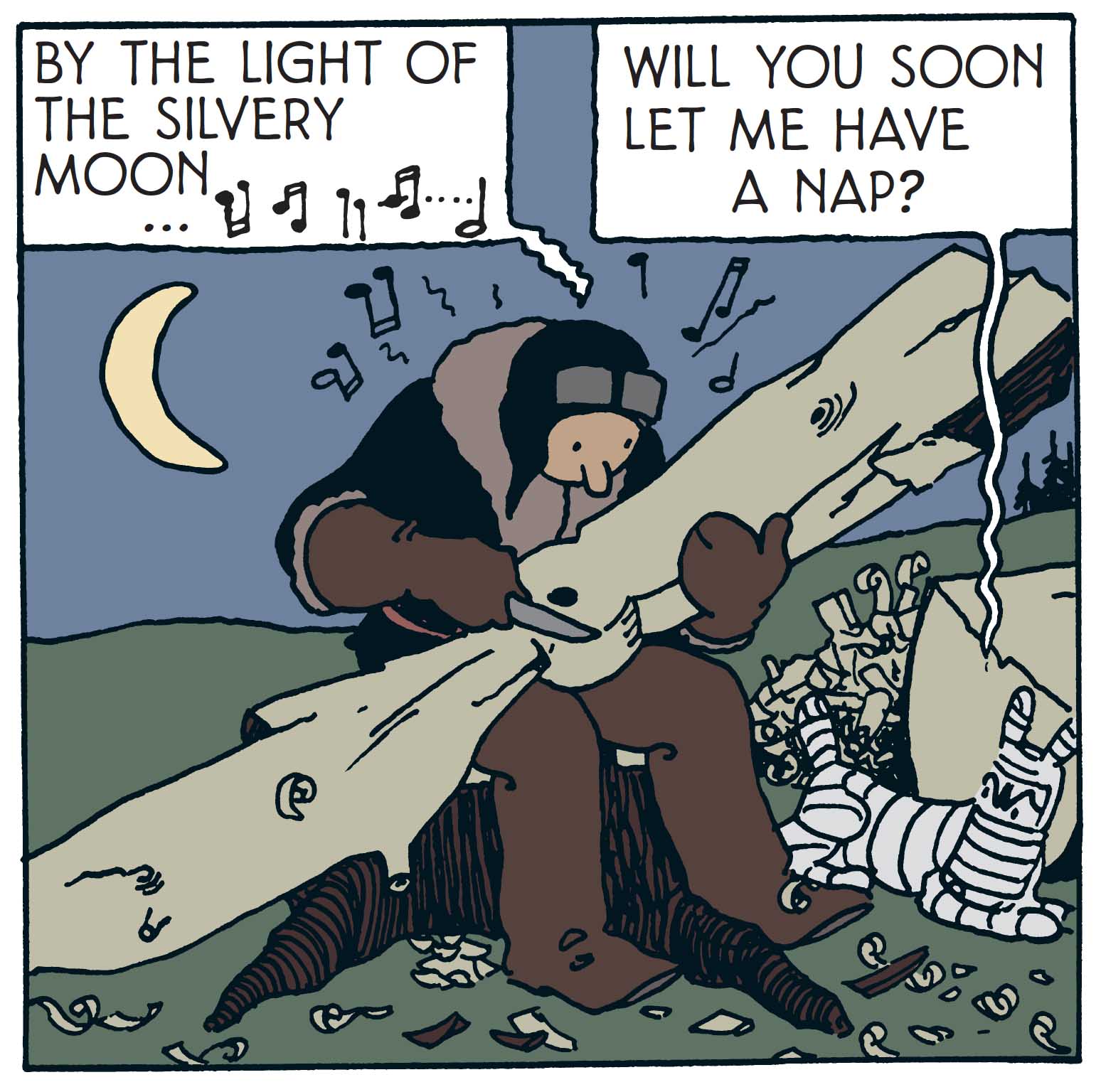

In Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the mythical “Moonlight” has several effects. Firstly, it evokes the passing of time. Secondly, if Hergé makes his hero sing, it's to underline the magnitude of the task he has to accomplish. In order to continue his adventures, he has set himself a challenge that is as unlikely as it is arduous. Namely, to carve an aeroplane propeller - out of a tree trunk - with a penknife, no less! But since nothing is impossible for Tintin, the young man logically succeeds in his goals. And, of course, in the end, Hergé couldn't help laughing at the situation as his young protege performs this prodigy, in the lighting conditions as described in the song.

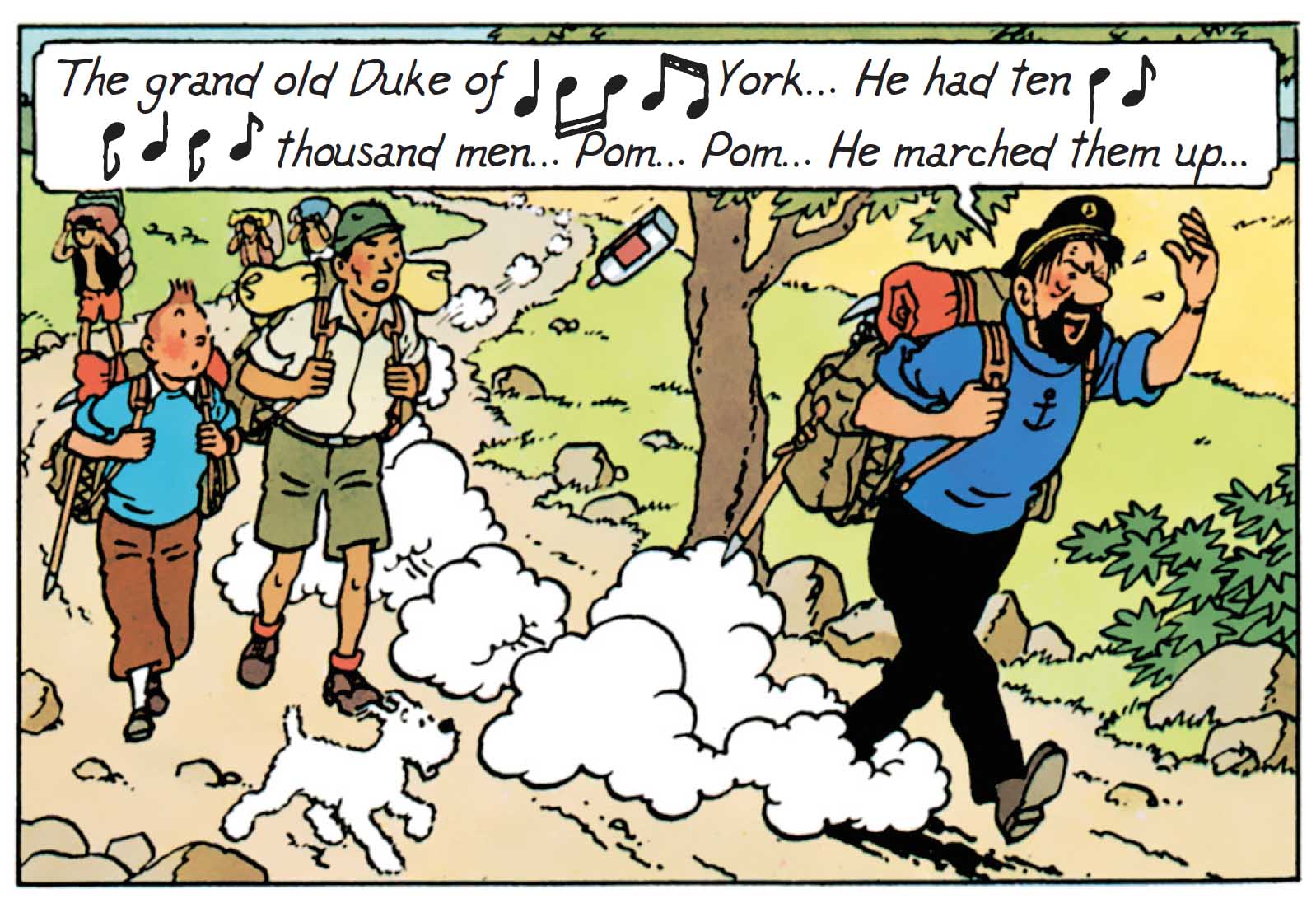

In Tintin in Tibet, after three long superimposed panels - which recount the facts in a few words and images - Hergé leaves it to Captain Haddock to link up with the next vignette. But the man is tired. So he needs a drop of his favourite magic potion. No sooner said than done, and he's rejuvenated... and enchanted. And so, at full speed, and singing a military march entitled “The Grand old Duke of York”, he tries to motivate the troops to step up the pace.

And what could be more picturesque than to use folk and traditional songs to bring a touch of the exotic to The Adventures of Tintin? In stories that send his characters off to meet distant peoples and civilisations, Hergé relies on such compositions to give his frescoes a touch of otherworldly realism.

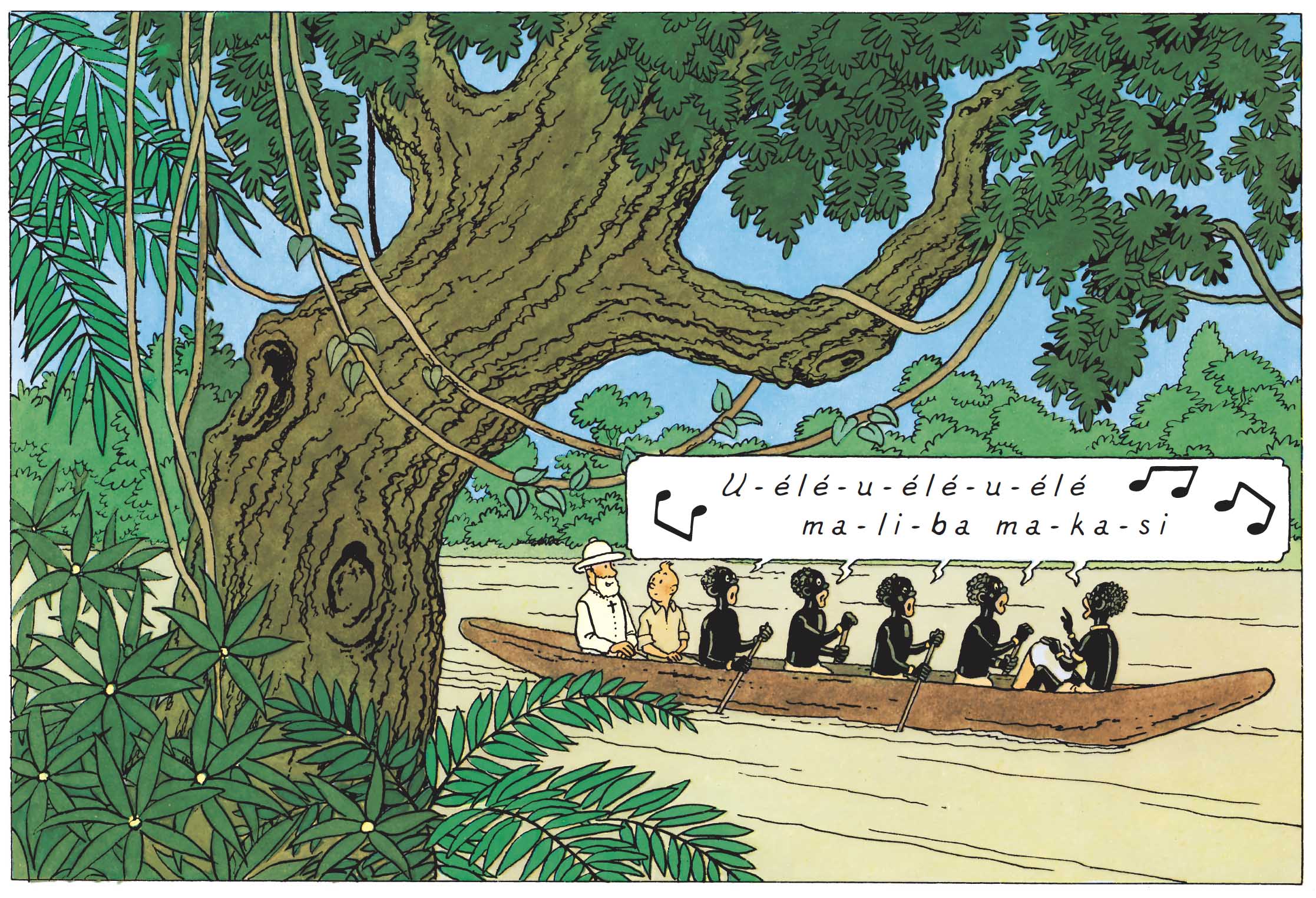

For example, halfway through Tintin in the Congo, young natives in a pirogue row together to “Uélé maliba makasi”. For the occasion, Hergé even transformed this African lullaby into a work song, separating each syllable with dashes, to support their efforts and enable readers to keep up.

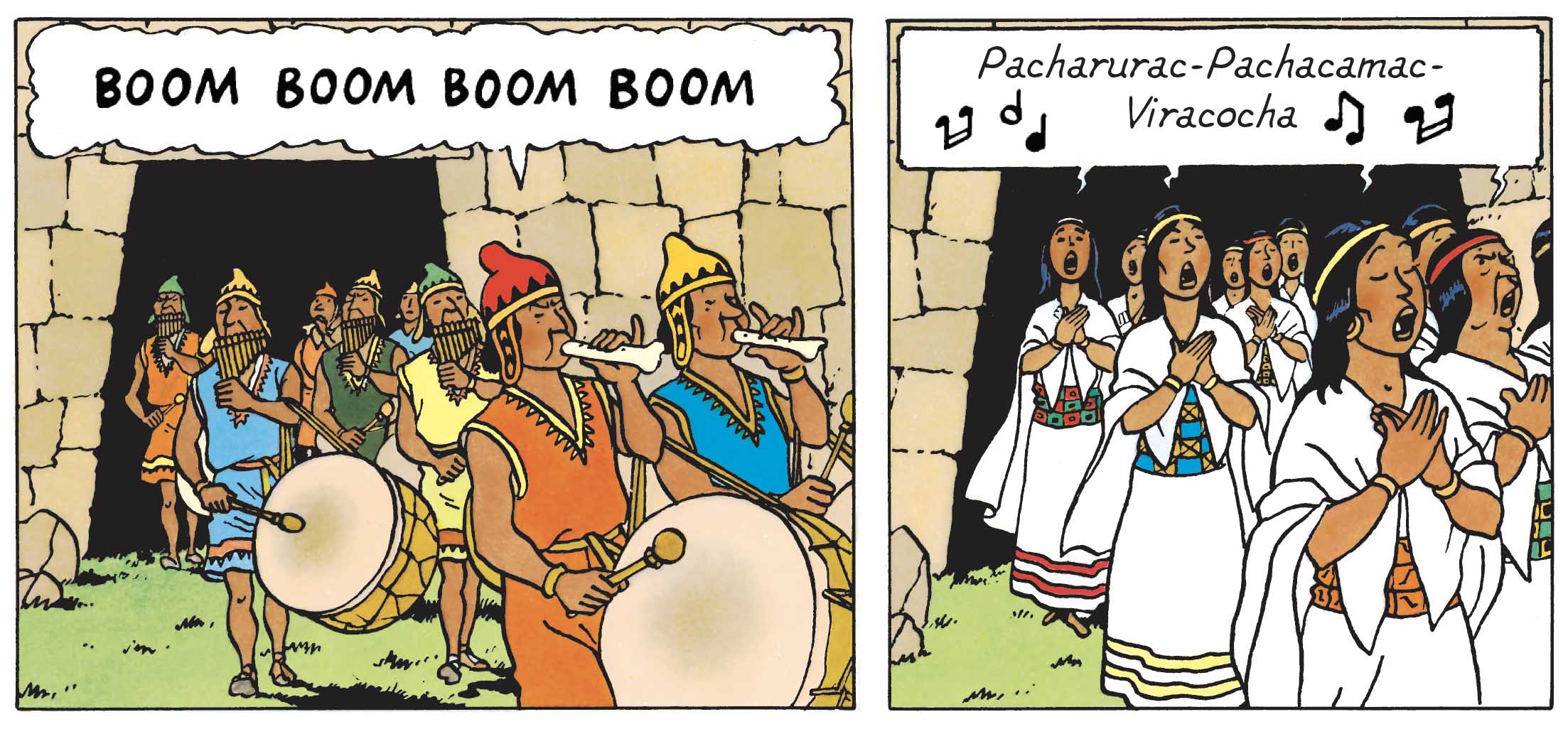

The same trick is used in Prisoners of the Sun. Although this time, it's the names of deities that are spelled out in dashes: “Pacharurac - Pachacamac - Viracocha”. Logical, given that the aim here is to invoke them - indeed, to summon them - as part of a ritual sacrifice. What's more, thanks to a women’s choir beating to the rhythm of the drums, Hergé offers his readers a disorienting cultural immersion and a surprising ethnographic dimension to his story.

Deja vu all over again

“The Jewel Song” is, of course, THE hit of The Adventures of Tintin. This lyrical gem - written by Charles Gounod for the opera Faust in 1859 - has a total of sixteen hits. Needless to say, it's played over and over again throughout the saga, and even several times in some adventures.

This is what industry professionals call “hype”. In other words, the over-broadcasting of a song so that it enters all - or almost everyone’s - heads and ears. This principle was invented in the 1950’s by Lucien Morisse (then Programme Director of radio station Europe n°1), to gain maximum exposure for one of his young proteges and make her song a hit. This is how Dalida, the singer of “Bambino”, was propelled - in just a few days - to the forefront of the French music scene.

For Hergé, the aim was not to promote an artist, but rather to comically reduce her to her biggest hit. Castafiore performed it seven times “live” and five times it was “recorded”.

.jpg)

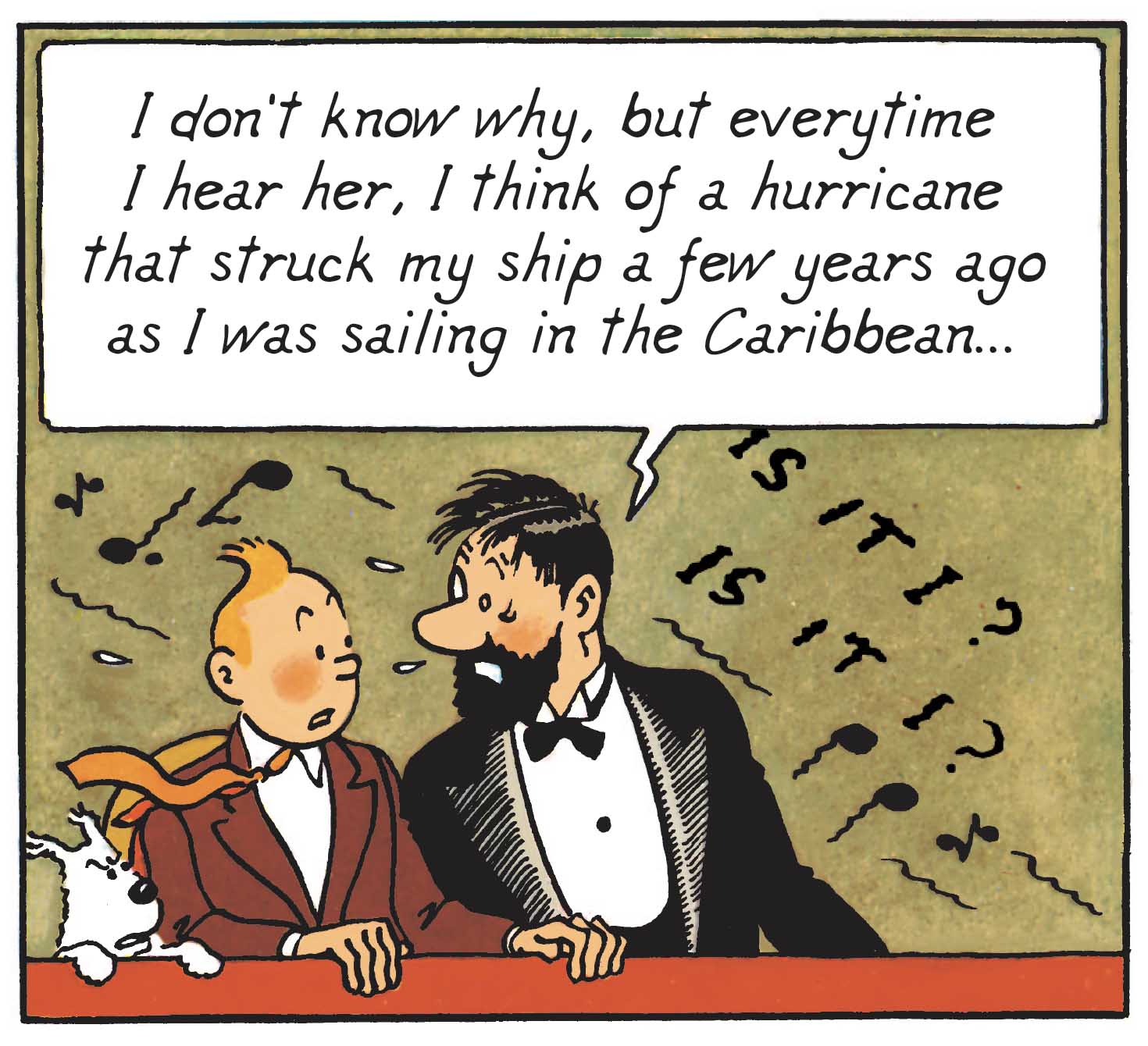

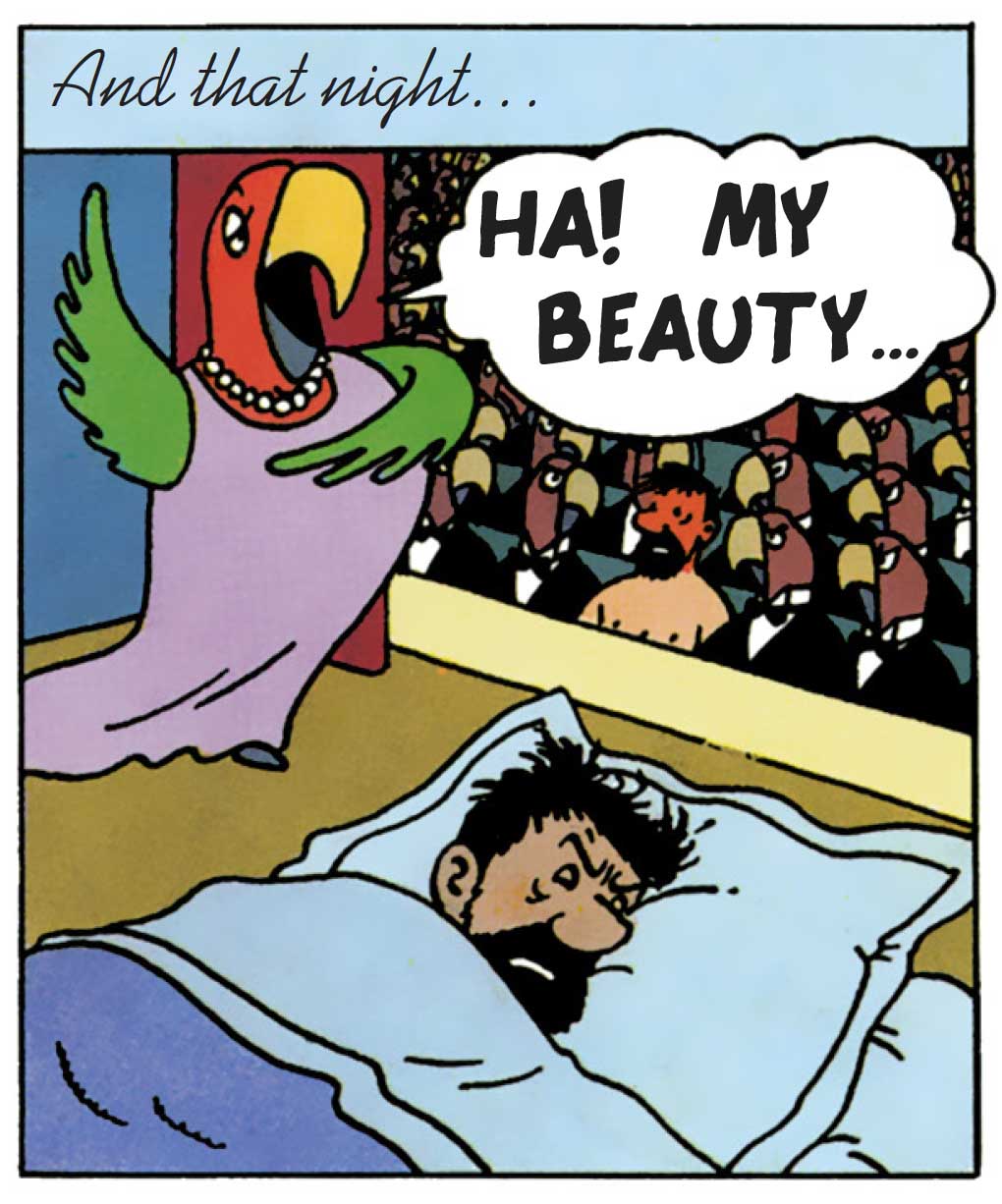

Readers will also see that, by dint of persuasion - and repetition, above all - she has even managed to create emulators. And among admirers and detractors alike. In The Calculus Affair, for example, Colonel Sponsz mechanically intones the first notes of this bravura piece to demonstrate his current good mood. As for Captain Haddock, he dares to do it in Destination Moon and The Castafiore Emerald, to mock the deafening diva a little more. In fact, in this adventure, he seems to have the greatest difficulty in ridding himself of this air. It possesses him even in his sleep, to the point of nightmares. And, for the occasion, it's not him, but Iago who is mocking the refrain.

We've come to the end of this fabulous singing tour. So, as a reminder, here is the complet setlist of songs featured in The Adventure of Tintin. To download it, click here.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2024

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books