"The Castafiore Emerald": Hergé’s Take on Vaudeville

Kappock, Koddack, Kosack… Bianca Castafiore never misses a chance to mangle poor Captain Haddock’s name with outlandish nicknames, all while assaulting his ears with her formidable vocal performances. And yet, his troubles have only just begun in this whirlwind of high-society disasters… The Castafiore Emerald is one of the most unconventional albums in the Tintin universe. Published in 1963, it stands out thanks to a remarkable narrative paradox: there is no grand investigation, no conspiracy with hooded figures — and yet everything is constantly in motion. But without a globe-trotting adventure or thrilling chase, can it still be considered a classic Tintin story? No matter — it remains one of the most dynamic and dialogue-rich albums in the entire series.

Hergé conceived this escapade as a almost intimate experiment. Amid a period of personal and creative doubt, he chose to step away from exotic adventures and immerse Tintin in a domestic fiction rooted in routine. The choice to set the entire story at Marlinspike Hall was a deliberate and crucial one. It creates a comic sense of saturation, where the slightest mishap escalates into absurd proportions.

This article proposes to read the album as a theatrical vaudeville piece transposed into the medium of comics. Through a play of misunderstandings, entrances and exits, and constant background noise, Hergé constructs a modern comedy of manners — centered on social dynamics and deceptive appearances.

A Burlesque Chamber Drama

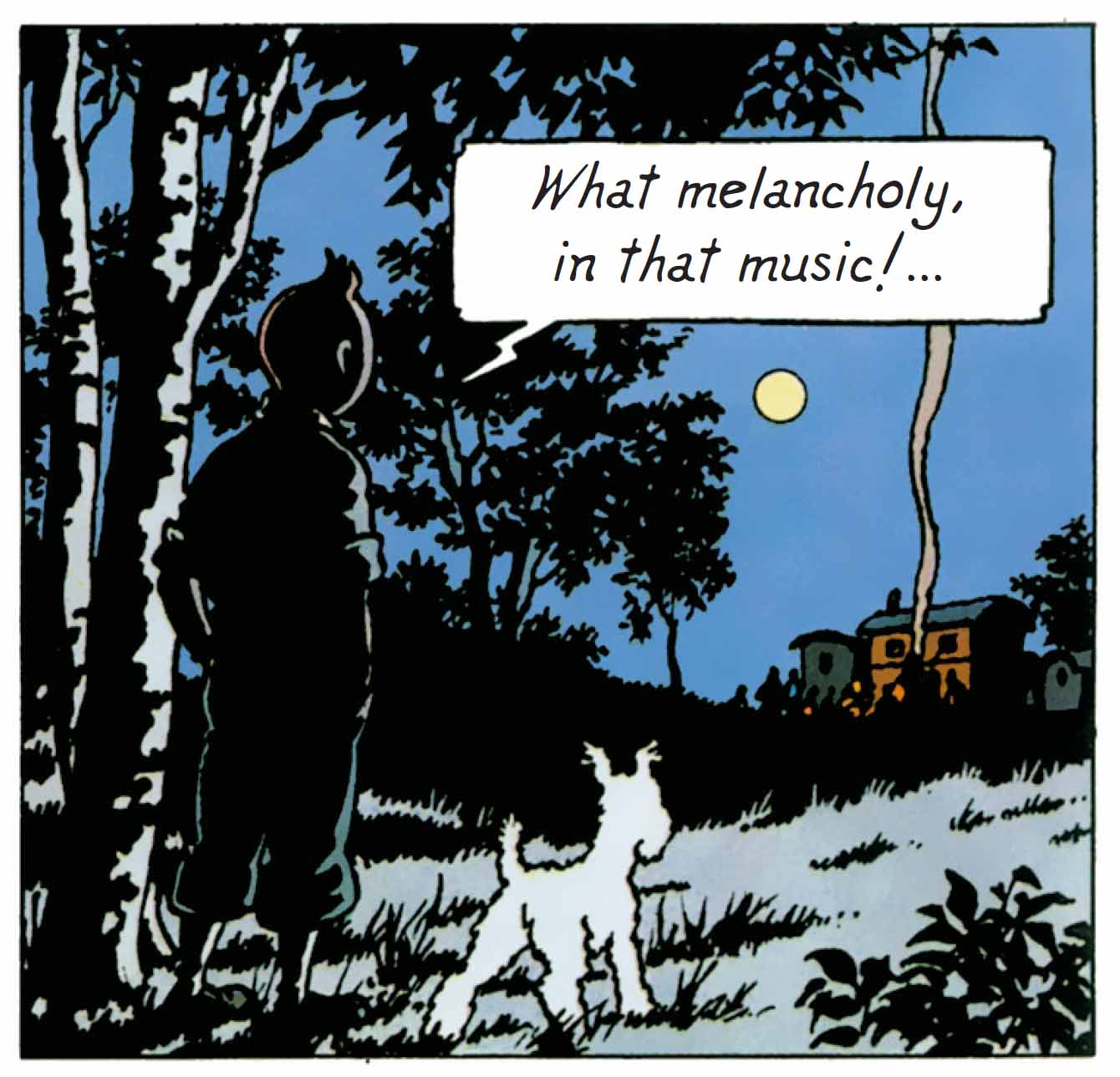

The entire album unfolds almost exclusively at Marlinspike Hall, the quintessential closed setting. In true boulevard theatre fashion, the action unfolds within a confined space where characters come and go, cross paths, dodge one another, or spy from the shadows.

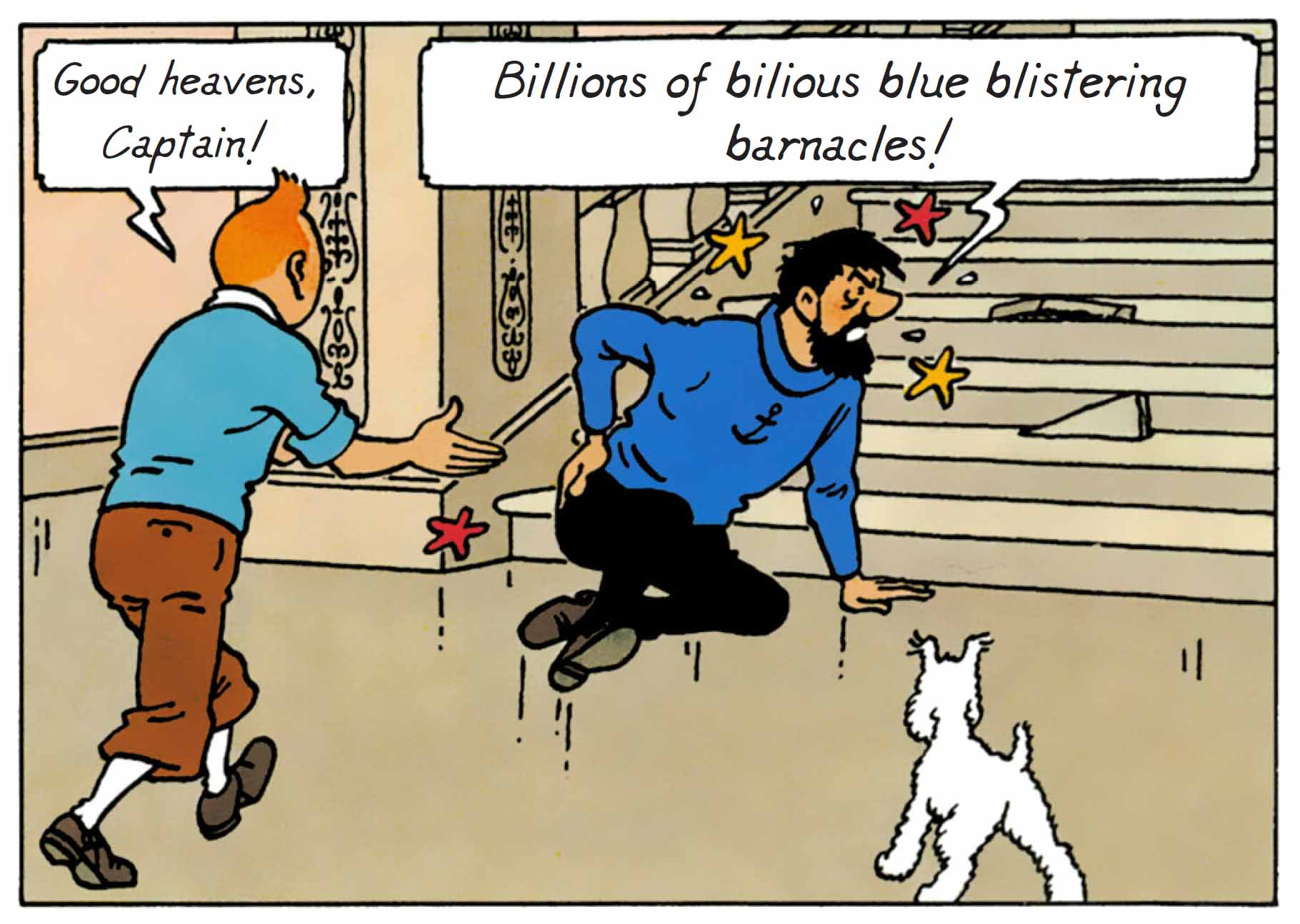

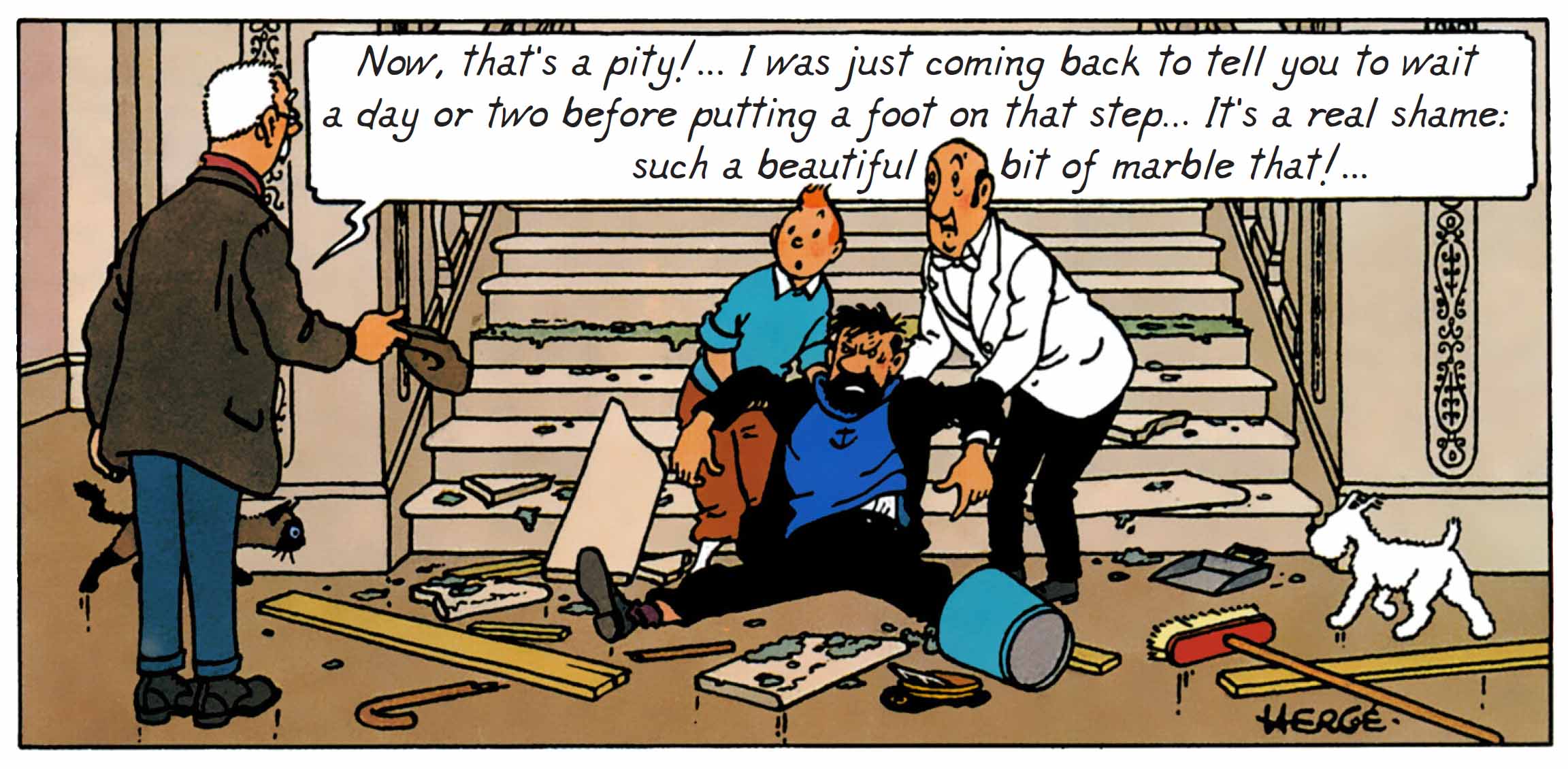

The château turns into a proscenium stage, with the front doorbell as a recurring nuisance, the entrance staircase as a sworn enemy, and a series of misunderstandings unfolding with the relentless precision of clockwork.

The choice of a closed setting is all the more striking as it runs counter to the usual logic of Tintin’s adventures, which are typically driven by movement, travel, and exotic locales. Here, there’s no sense of displacement: Hergé sets his entire plot within a familiar, motionless frame. This retreat to Marlinspike is a bold, almost experimental gesture. It transforms the château into a character in its own right — a theatre of tension, miscommunication, and organized chaos. Each corridor is a stage for showboating ; every door opens onto a new misunderstanding.

This apparent stillness — a stable, recurring set — heightens the comedy of repetition. Each room in the château plays a distinct role:

This confined setting also allows for the rhythm of a chamber play, intensified by a cascade of unexpected visitors — journalists, television crews, gypsies, technicians — each more absurd than the last. The commotion originates from outside but crashes against the château’s walls like a constant back-and-forth, never truly altering the setting or its overall pace.

The contrast between the stillness of the place and the chaos within creates a constant comic tension — a theatrical staging of disrupted boredom, where everything feels simultaneously too quiet and perpetually on the verge of exploding.

The Comedy of Repetition

The most visible and deliberate device in the album, the gags return like a boomerang. “Where is that blasted stonemason?!” exclaims the exasperated Captain. Whereas in other Tintin adventures, actions are singular and geared toward advancing the plot, The Castafiore Emerald is built on cyclical situations that repeat in loops. This repetition is no accident: it is carefully crafted by Hergé, who orchestrates each gag like a musical variation on a common theme.

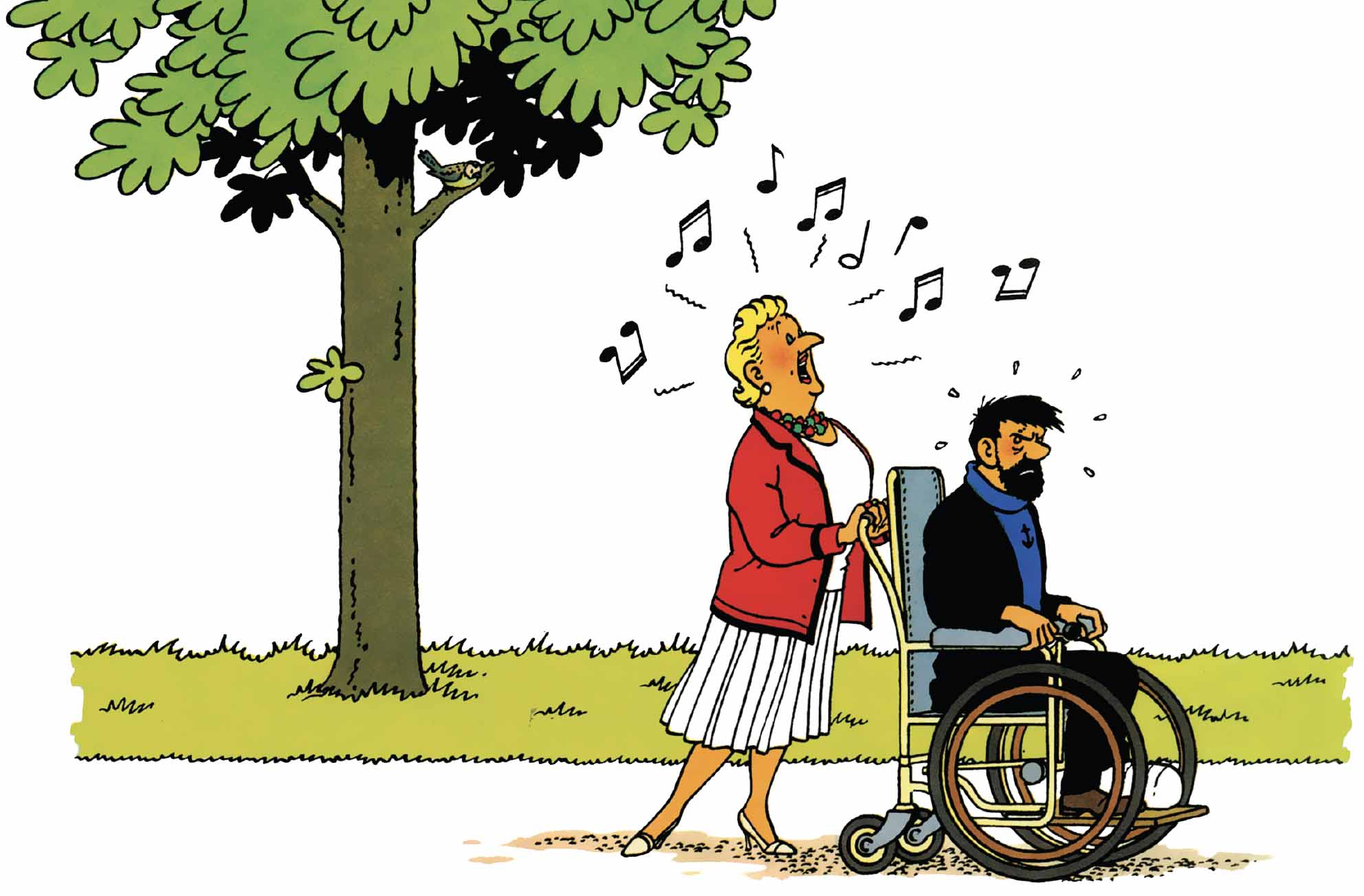

Captain Haddock is at the heart of this comic mechanism : he tumbles down the stairs, struggles to reach the stonemason, and never manages to find peace. These gags are never one-offs: they reappear — sometimes identically, sometimes with slight variations — always with the same visual impact. Haddock’s physical comedy reflects his loss of control in the face of his domestic space being invaded by uncontrollable outside forces (Castafiore, journalists, technicians, gypsies...).

Sound effects play a key role in this dynamic. Typical onomatopoeia fill the panels like the sound cues of boulevard theatre. The château becomes a resonating chamber — a living set that creaks, slams, crashes, and groans, making the vaudeville feel tangible. The absence of a linear plot is compensated for by a comedic choreography in which every noise becomes a narrative trigger.

To this are added recurring visual motifs:

This repetitive structure reinforces the theme of entrapment. Since nothing really progresses, the characters quite literally go in circles. It’s a comedy of the absurd, where the same actions trigger the same disasters, and no lessons are ever learned.

Finally, Hergé uses this repetition as a form of parody — gently poking fun at his own narrative conventions while pushing them to the extreme. The result is an album with a unique flavor: funny, claustrophobic, and remarkably well orchestrated.

The Misunderstanding as a Dramatic Engine

In the tradition of vaudeville, misunderstanding is the spark that sets everything ablaze. Hergé builds his entire narrative around a series of misinterpretations, baseless suspicions, and hasty conclusions. It all begins with a trivial event: the apparent disappearance of the opera singer’s jewels. This disappearance — in reality, a simple misplacement — becomes the trigger for full-blown collective paranoia.

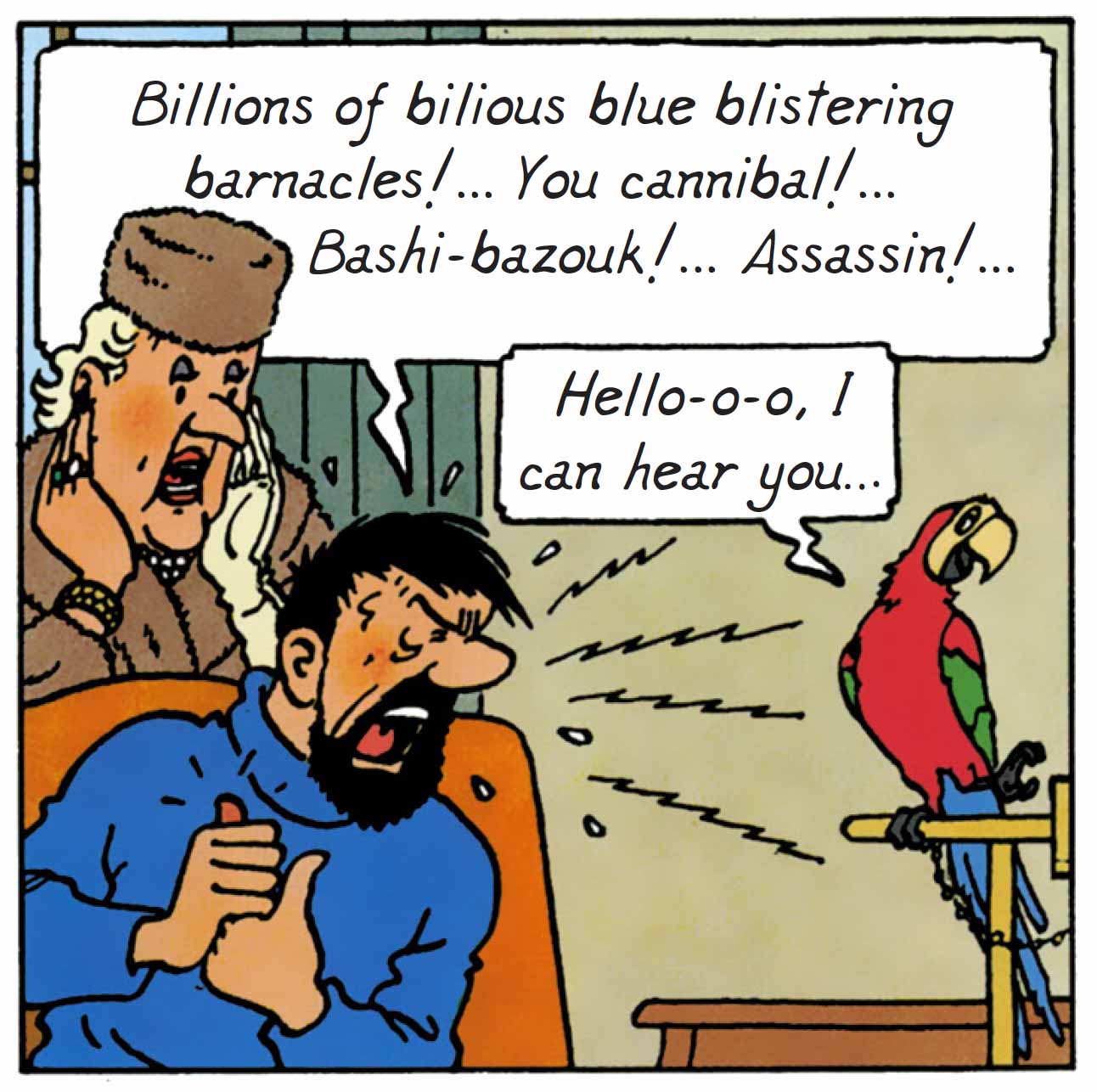

From the moment the alleged theft is discovered, every character begins constructing their own theory, without ever stepping back to consider the bigger picture. Castafiore swiftly — and without evidence — accuses her maid Irma. Thomson and Thompson, called in for reinforcement, turn their attention to the gypsies camped in the nearby field, based solely on prejudice. Even the parrot, with its repeated cries of “Thieves!”, becomes a suspect in some eyes, or at least a witness worth interrogating. Captain Haddock, for his part, takes refuge in constant exasperation, though even he occasionally lends an ear to the swirling rumors.

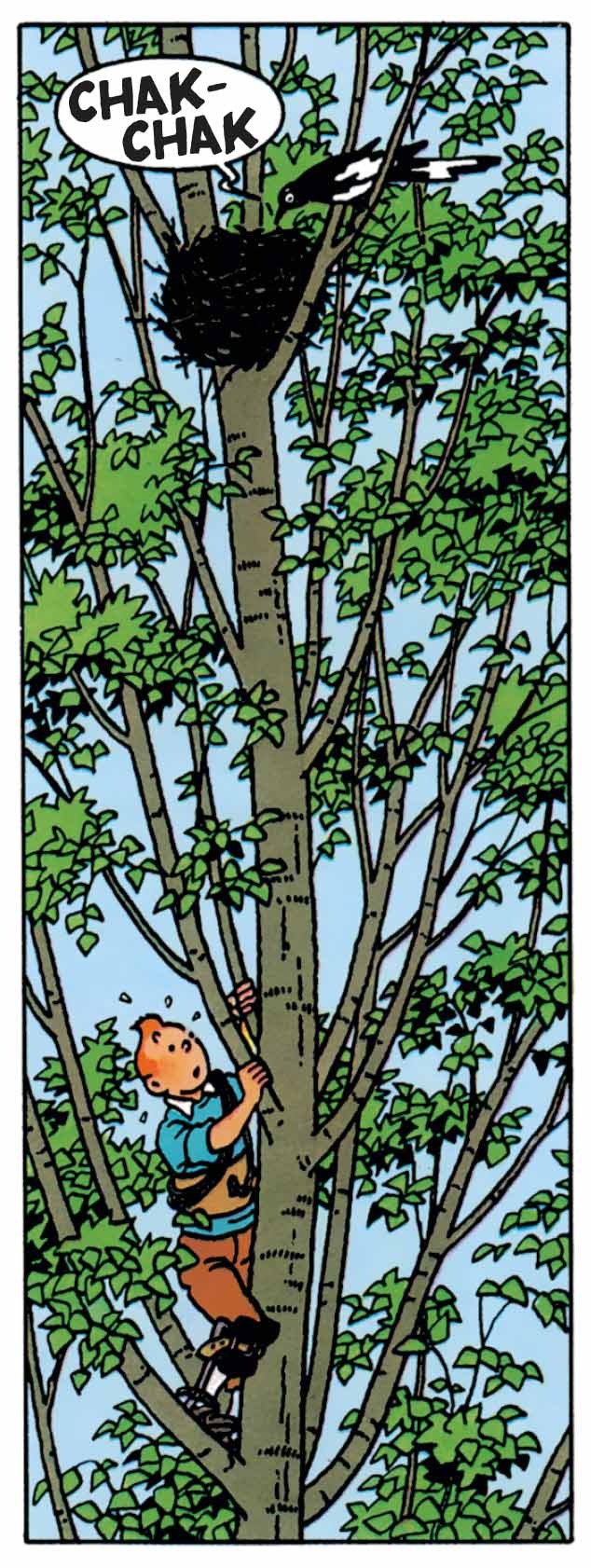

Tintin, ever the sharp observer, keeps his distance from the chaos. He is the only one who resists the spiral of generalized suspicion. It is, in fact, Tintin who eventually uncovers the truth: the jewels were never stolen — they were simply taken by a magpie. This deliberately anti-climactic, even absurd resolution, caps off a series of biased clues, misread signs, and overblown reactions.

This entire dynamic hinges on a carefully orchestrated series of misunderstandings. The parrot becomes a comedic conduit for suspicion by repeating phrases out of context. The presence of the gypsies, initially accepted by Haddock, gradually becomes a source of mistrust based solely on gossip. Irma’s naturally discreet demeanor is consistently misread as suspicious.

The château becomes a kind of paranoid microcosm, where everyone projects their fears onto everyone else. It is here that the album sets itself apart from classic adventure tales: there is no villain, no conspiracy, no crime — only a series of mistaken interpretations.

This narrative choice turns the album into a true study of suspicion, where misunderstanding reigns supreme. Hergé, while playfully borrowing the tropes of detective fiction, subverts its rules. The implicit moral is clear: the real drama isn’t the theft — it’s the climate of suspicion it unleashes, and which everyone unknowingly helps to fuel.

Parody of Fame and Gentle Satire

The Castafiore Emerald is not merely a domestic vaudeville — it is also a subtle satire of the media, celebrity, and the way public image is shaped — and sometimes distorted — by those who observe it, produce it, or endure it. Through the character of Castafiore, Hergé offers a bittersweet critique of the star system and its inherent absurdity.

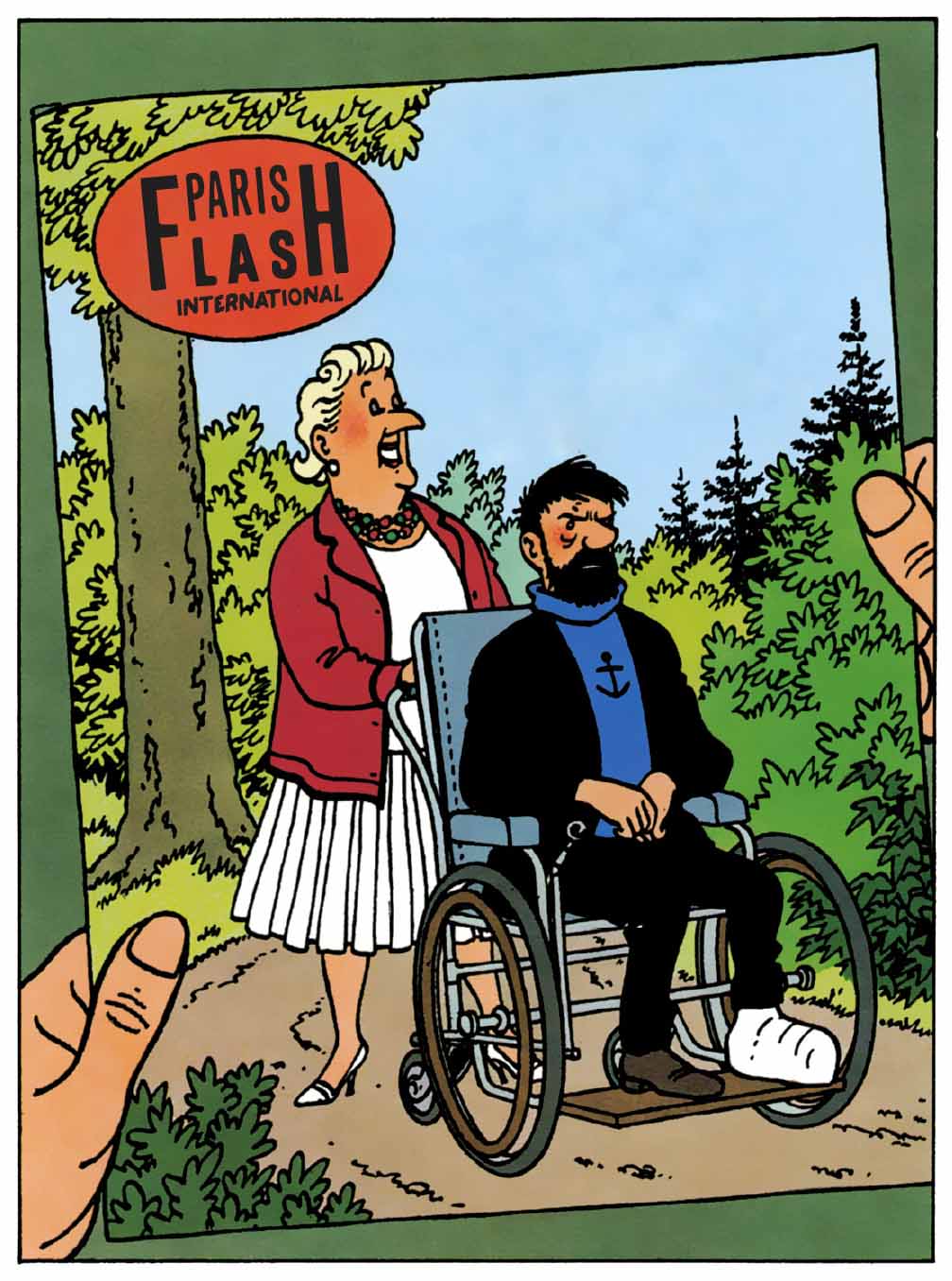

From the moment the journalists from Paris-Flash International, one of the narrative threads of the story is established: the gap between reality and representation. Castafiore has not actually invited the press — she discovers the newspaper’s presence through an article published without her consent, announcing supposed engagement plans with Captain Haddock. The humor immediately springs from this fabricated news, which deeply embarrasses the Captain and only faintly flatters the diva. This episode highlights the media’s distorting role: a simple visit is spun into a romantic affair, and the misunderstanding becomes public and uncontrollable.

This intrusive media treatment continues with the arrival of a television crew sent to film Castafiore. The technicians take over Marlinspike Hall’s drawing room with grotesque nonchalance: cables strewn across the floor, blinding lights, and an invasive camera. Hergé draws the scene with clear irony, emphasizing the carelessness or technical indifference of the journalists, more concerned with creating spectacle than with accuracy.

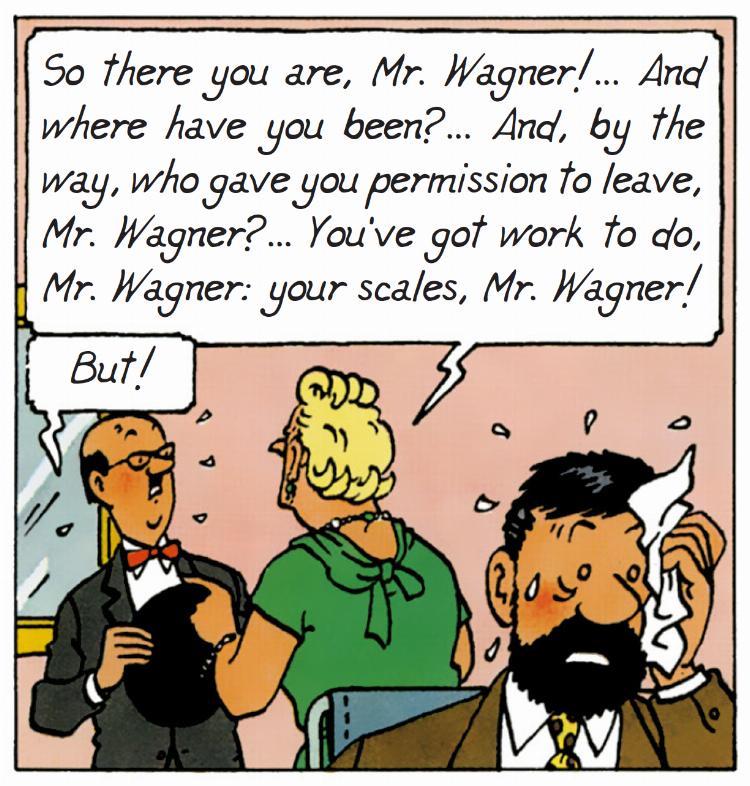

Castafiore herself is a parodic figure: an exuberant, often caricatured diva, she is coquettish and theatrical. She is not simply a victim of the media system — she plays into it as much as she suffers from it. She controls her entrances, stages her jewelry, and adorns herself with her operatic airs — notably the “Jewel Song” from Faust, which she performs repeatedly like a comic refrain.

This repetitive and deliberately overbearing aspect of celebrity becomes a comic device in its own right. Castafiore embodies the self-contained stardom that spins in circles. She seeks admiration, yet meets only Haddock’s irritation, Tintin’s skepticism, and the bumbling of Thomson and Thompson.

Hergé also uses this context to caricature media figures:

The Castafiore Emerald is not merely a domestic vaudeville — it is also a subtle satire of the media, celebrity, and the way public image is shaped — and sometimes distorted — by those who observe it, produce it, or endure it. Through the character of Castafiore, Hergé offers a bittersweet critique of the star system and its inherent absurdity.

Finally, this gentle satire plays out in a hall of mirrors: the château of Marlinspike Hall, supposedly a haven of peace, becomes a stage for public display — a set for cameras and flashbulbs. The private is invaded, the everyday becomes spectacle, and the characters struggle to reclaim control over their own image. This is where Hergé’s critique lies: in a world saturated with external gazes, no one seems to know anymore what is real, performed, or projected.

The Absence of a Complex Plot

In The Castafiore Emerald, Hergé makes a radical narrative choice: he abolishes the traditional plot. There is no real crime, no faraway adventure, no mystery to solve — at least not in the conventional sense. The storyline, if it can be called that, fits into a single line: a precious object (the jewels) disappears… and then reappears. And yet, the album manages to captivate the reader from beginning to end.

This apparent emptiness is offset by a tightly constructed comic structure, based on repetition, interpersonal tensions, and internal movement within the château. Hergé borrows the codes of boulevard theatre: entrances and exits, misunderstandings, hushed domestic squabbles, and revelations without consequences. He shifts the usual narrative stakes to better explore situational comedy.

The story becomes a kind of variation on inaction — or rather, on the illusion of action. Everything seems to move, speak, fall, suspect — but nothing truly progresses. This phenomenon creates a kind of comic hypnosis, in which the reader laughs less at a single gag than at the fact that the gag repeats itself, or that a situation escalates for no real reason.

The strength of the album lies in its ability to create dramatic tension without drama.This boldness partly explains why The Castafiore Emerald puzzled some readers when it was first released — but also why it is now considered one of the most refined and unique albums in the entire series. It perfectly illustrates the power of comic structure, especially when that structure revolves around a non-event.

Conclusion

The Castafiore Emerald stands as a truly singular entry in the Tintin universe. Where readers expected an adventure, Hergé offers an anti-adventure. Where one might anticipate a mystery, he presents a false enigma. This deliberate subversion of expectations transforms the album into a stylistic exercise that is at once comic, satirical, and masterful.

By choosing Marlinspike Hall as the sole setting for the action, Hergé tackles the narrative challenge of the closed-room drama, but with visual tools borrowed from theatre and comedic cinema: pratfalls, sound effects, repetitions, misunderstandings, situational comedy, and above all, the precisely timed choreography of entrances and exits. Each page unfolds like a boulevard play: the characters bustle about, misinterpret one another, make accusations — yet never truly advance.

This is where the album’s modernity lies. Hergé isn’t telling a story about an event — he is staging human behaviors: suspicion, bad faith, the hunt for a culprit, fear of media scrutiny, the thrill of gossip. He observes his characters within a confined space, where tensions are heightened by the absence of escape. The result is a comedy of observation — sometimes gentle, sometimes biting, but always tightly controlled.

Often underrated and occasionally misunderstood, The Castafiore Emerald reveals its richness upon rereading. Beneath the apparent lightness of its dialogue and gags lies a jeweler’s mechanism, where structure replaces plot, and humor springs from the smallest events of daily life.

In doing so, Hergé perhaps revealed more about his characters — and their humanity — than in any globe-trotting adventure… and more about us as readers, ever eager to uncover a mystery, even one hidden in a simple nest.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)