Full Speed Ahead! Tintin Behind the Wheel

It growls, it smokes, it bursts into view, crashes spectacularly—and often saves our quiff hairstyle hero from disaster. In Hergé’s world, the automobile is no mere object: it is a four-wheeled creature, never truly at rest. It carries Tintin across continents, sends him hurtling into ravines, delivers him from enemies, or propels him into the arms of fate. And paradoxically, it is almost never his own.

In 1938, at the age of 31, Hergé bought his first car: an Opel Olympia Cabriolet Coach. What seems trivial today was, at the time, a minor milestone. Back then, owning a car was still a privilege reserved for the few. This gap between aspiration and reality echoes in Hergé’s work: as a young reporter, Tintin was unlikely to own a car himself. And yet, automobiles are omnipresent in his adventures.

They streak through Hergé’s stories as a dynamic constant—at once a narrative device, a social marker, and at times a vehicle for satire. They spark chase scenes, trigger turning points, and reveal just as much about a character’s role as they do about their status.

So buckle up, fellow car enthusiasts—we’re shifting into first gear and heading full throttle into Tintin’s mechanical universe!

Tintin: A Hero Without a Steering Wheel

In the earliest albums, Tintin almost never owns a car. This absence isn’t a flaw, but rather a revealing choice. It likely mirrors the personal situation of Hergé at the time he created the character: at 22 years old, Georges Remi—Hergé—had no car, was working at the Belgian daily Le Vingtième Siècle in Brussels, and had limited financial means. Owning a car was still a dream. No matter! With pencil in hand, he began drawing a daredevil in 1929—little more than a sketch—by the name of Tintin, already embarking on brawls and improbable chases in mechanical contraptions. How does he manage to handle them? Realism hasn’t kicked in yet: Tintin commandeers vehicles or assembles them with little effort.

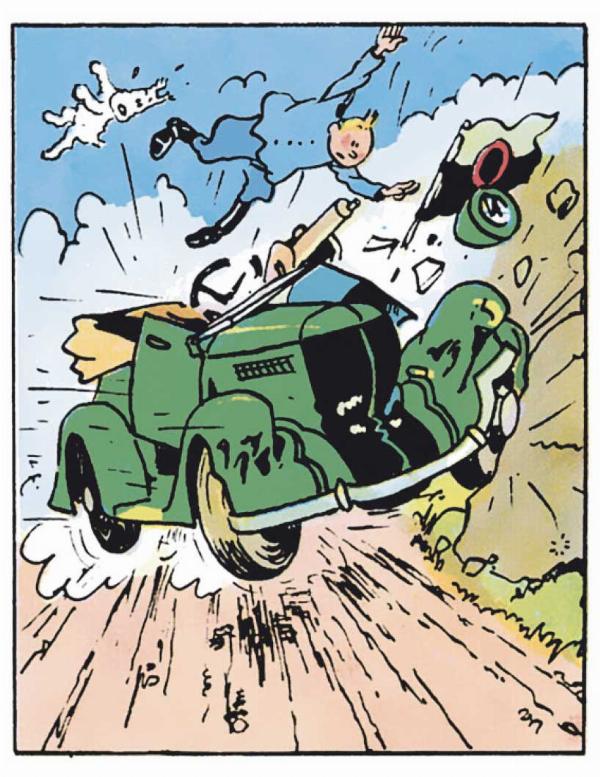

Early on, in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, he even buys a car—an Amilcar. The story doesn’t shy away from the outrageous: there are no fewer than four crashes or off-road incidents. The tone is set—car-related mishaps will become a recurring theme in Hergé’s work.

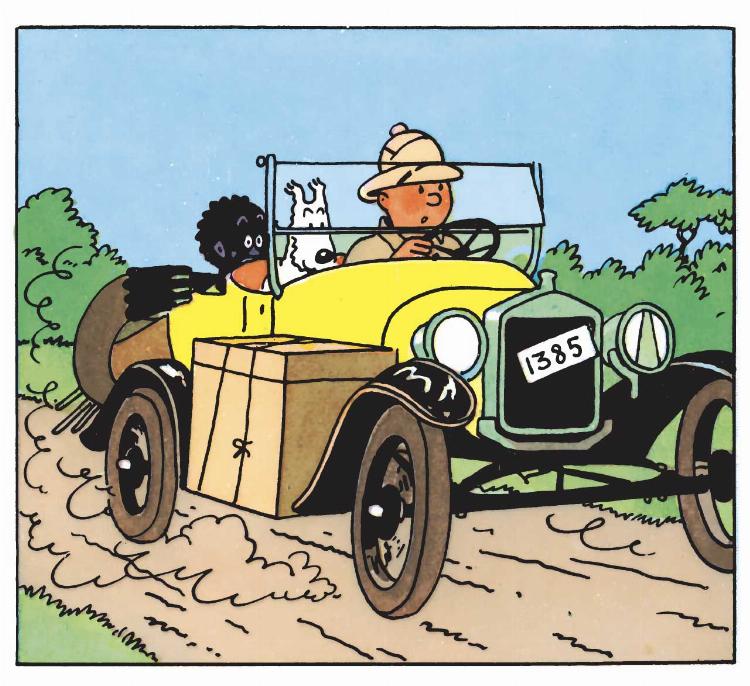

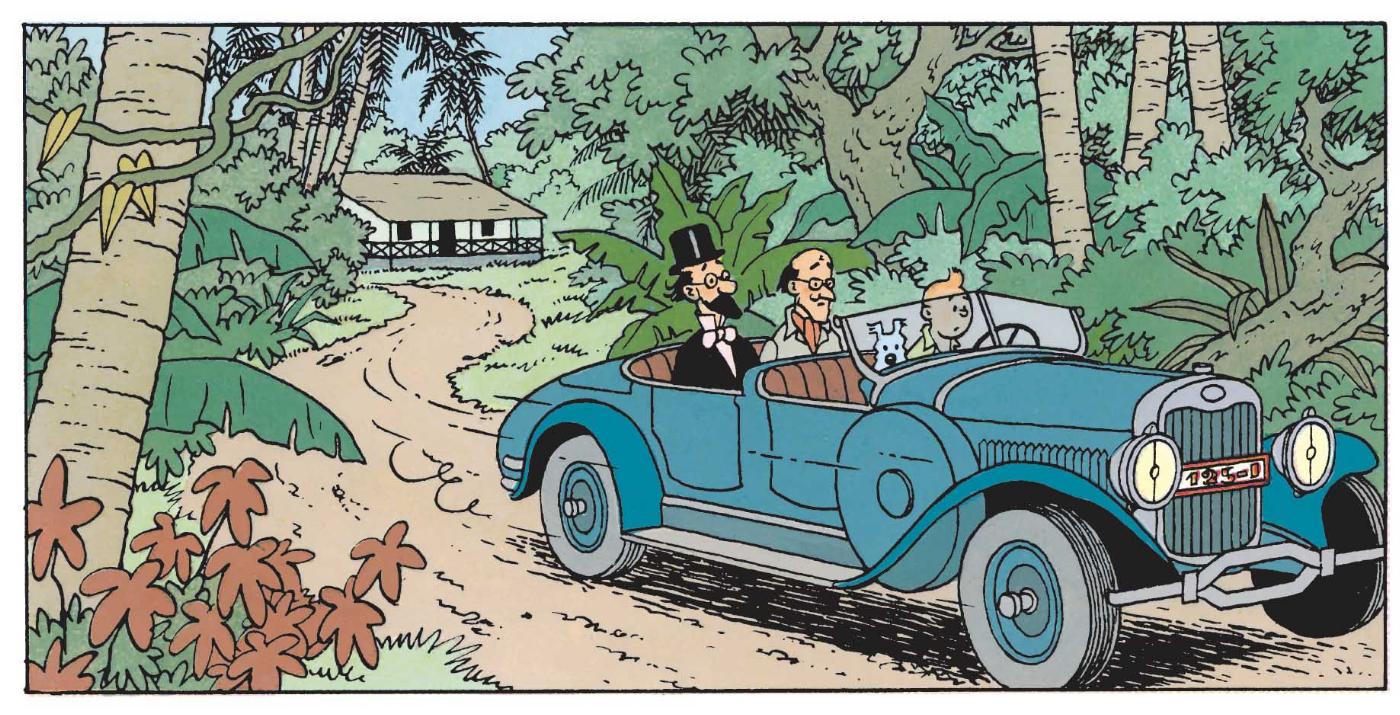

In Tintin in the Congo, he acquires a Ford T. These two vehicles are essentially the only ones Tintin ever purchases in the series, and only within specific narrative contexts, for defined journeys. From that point onward, Tintin is never again a car owner. Vehicles are either borrowed, temporarily offered, or seized in the heat of the moment.

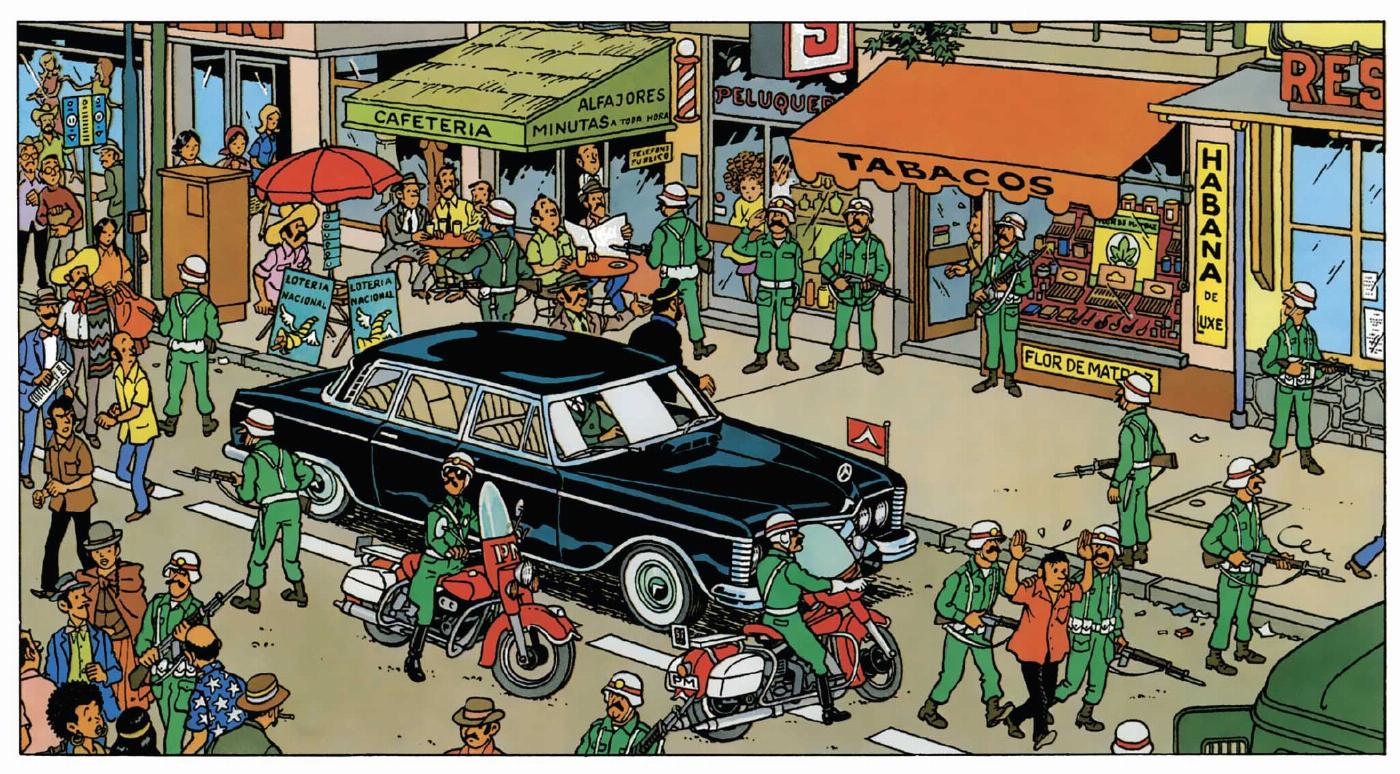

A car is more than a means of transportation: in Hergé’s world, it’s a social passport, a uniform, a clue. One trait shared by many of Tintin’s persistent enemies is their fondness for the iconic Mercedes. This starts early on with the SK model used by German police in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, continues with the 220 model driven by Bordurian agents about to abduct Professor Calculus, and leads to the 300 model operating under diplomatic cover in Geneva. And the cherry on top? In Tintin and the Picaros, the dictator Tapioca parades around in a limousine bearing—of course—a Mercedes badge. But not just any Mercedes. We’ll come back to that...

The Narrative Role of Borrowed Cars

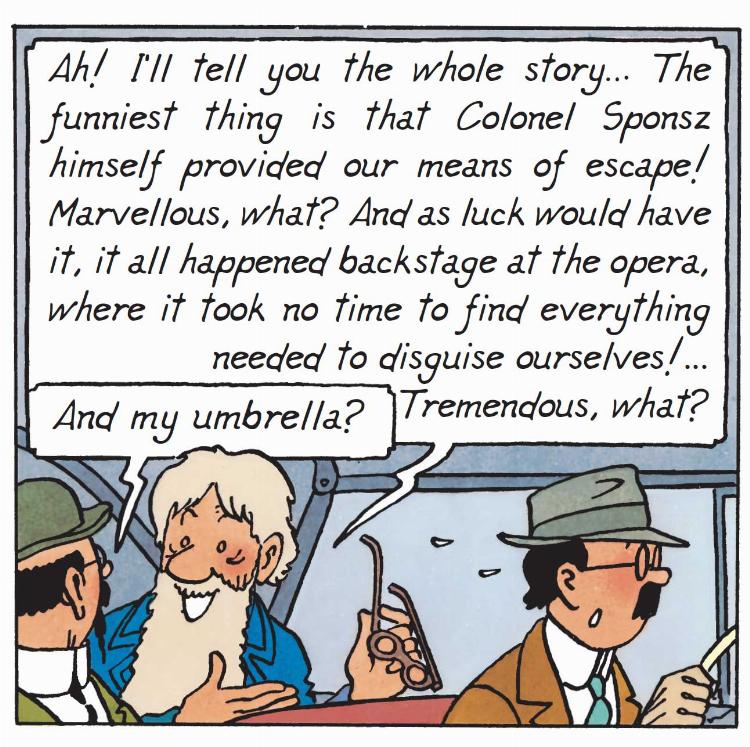

Like any respectable adventurer, Tintin makes regular and varied use of automobiles—as a passenger, a driver, and at times even an accidental thief. He borrows vehicles from allies (the Rosengart lent by Pablo in The Broken Ear, or the Lancia Aprilia provided by the Emir in Land of Black Gold), commandeers others in emergencies, or resorts to taxis as a last option. In The Crab with the Golden Claws, he tries to take an Amilcar model being towed away by a breakdown truck. In King Ottokar’s Sceptre, he hot-wires a car to chase after an Opel Olympia used by terrorists—yes, the very same model as the first car ever owned by Hergé himself.

In The Broken Ear, he fakes an accident by sending a car hurtling into a ravine. In The Calculus Affair, he commandeers—with remarkable flair—a Lancia driven by Signor Cartoffoli of Milan for a breathtaking high-speed chase. In many such instances, the vehicle is taken without explicit permission, but always for a good cause—revealing a hero unafraid to bend the rules when necessary.

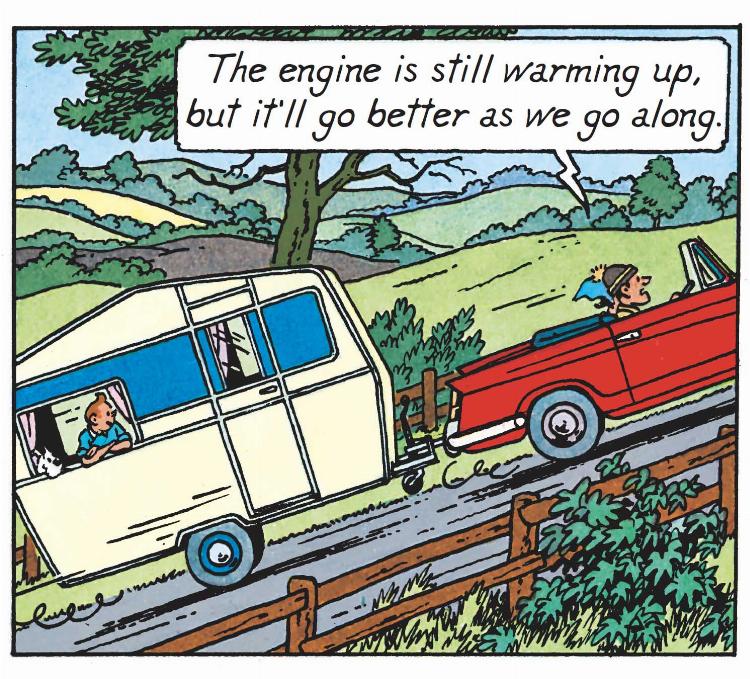

Unfortunately, cars don’t always fall from the sky. When no vehicle or driver is available, Tintin resorts to hitchhiking. In The Black Island, he travels in a caravan towed by a Triumph Herald—until the tow bar breaks and the trailer ends up in a pond. Sometimes, the ride must be refused: in The Calculus Affair, Haddock prefers to leap into a muddy ditch rather than get into a suspicious-looking Citroën. And in Tintin in Tibet, a comical scene shows Haddock riding down a slope on a cow, trying to flag down a taxi; the animal suddenly stops, and the captain is launched straight into the trunk of the car, much to the driver’s dismay.

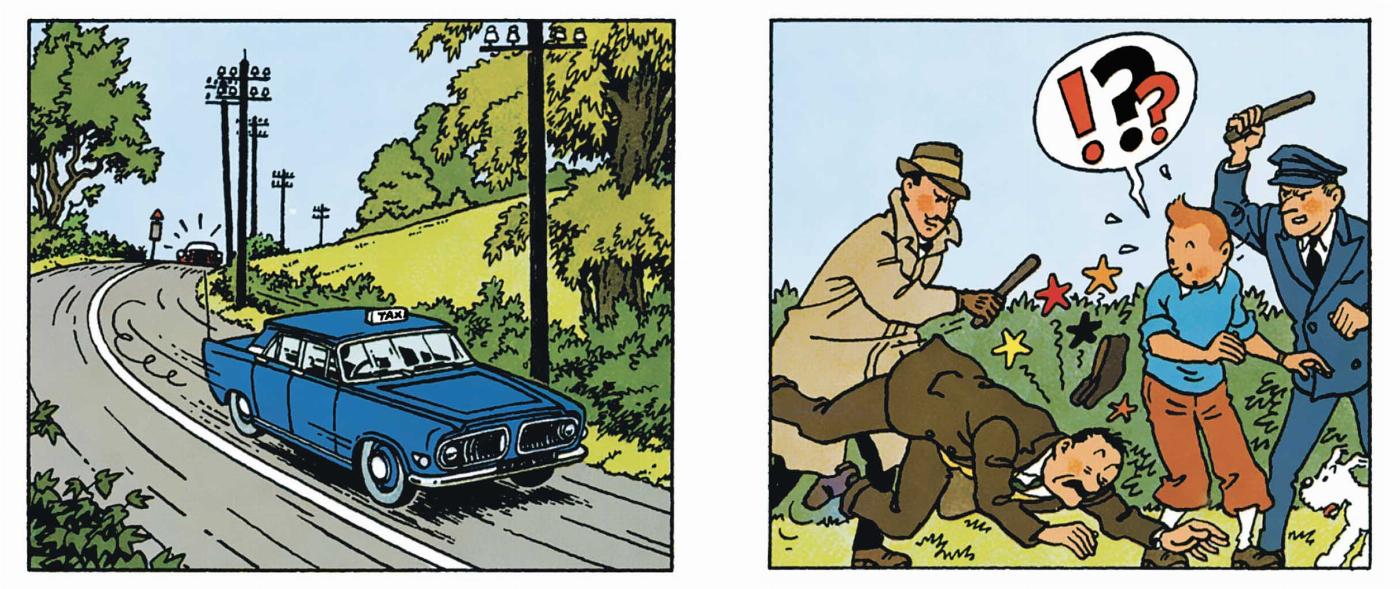

As mentioned, taxis are another frequent fallback. In The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Black Island, and The Calculus Affair, Tintin hails or hops into taxis—often with mixed results. Some drivers flee, others lose control of the car. On occasion, a taxi is even taken over by force—as in The Black Island, where the driver is simply knocked out cold. What can you say? Some days, it just isn’t safe to be behind the wheel.

Crashes, Chaos, and Mechanical Comedy

In Tintin, cars are rarely synonymous with comfort or stability. Instead, they give rise to perilous, outrageous, or downright absurd situations. In The Red Sea Sharks, Tintin and Haddock pursue Dawson, a notorious arms dealer, in his black Jaguar. Unusually for the series, the chase unfolds without incident—standing in stark contrast to the frequent car-related mishaps elsewhere.

By contrast, in The Calculus Affair, it’s not a Jaguar but a Chrysler that is pursued by Tintin, riding in Signor Cartoffoli’s Lancia Aurelia, in a scene brimming with speed and tension. In moments like these, vehicles become high-strung narrative tools, revealing the chaotic world the heroes are forced to navigate.

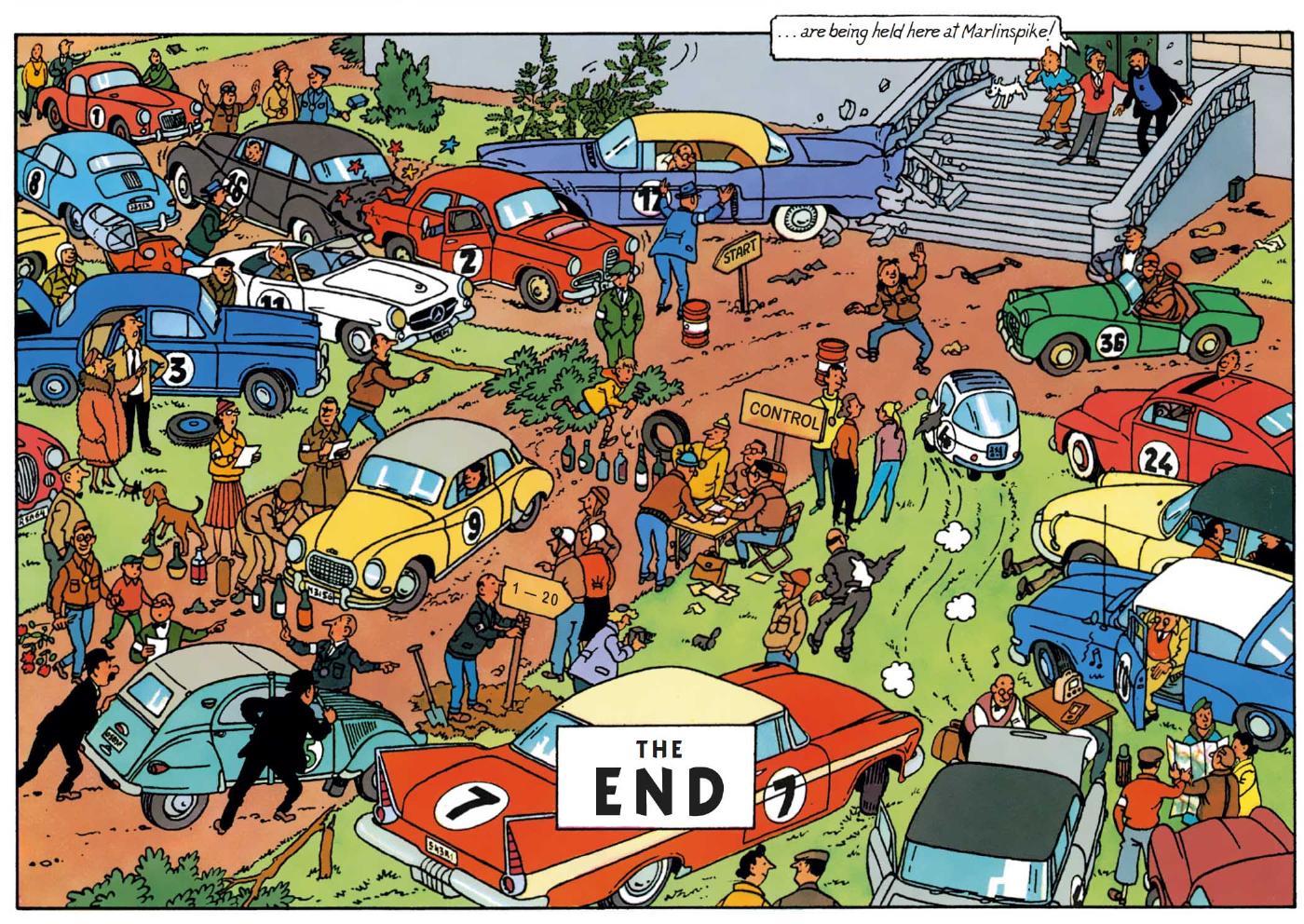

Even before the rise of typically Hollywood-style exaggeration, cars in Tintin could already explode (Cigars of the Pharaoh), swerve wildly off-road (Prisoners of the Sun), or crash into trees (The Calculus Affair). The record is arguably set in The Calculus Affair, when a parade of vehicles invades Marlinspike Hall: Cadillac, Plymouth, Alfa Romeo, Mercedes, BMW…

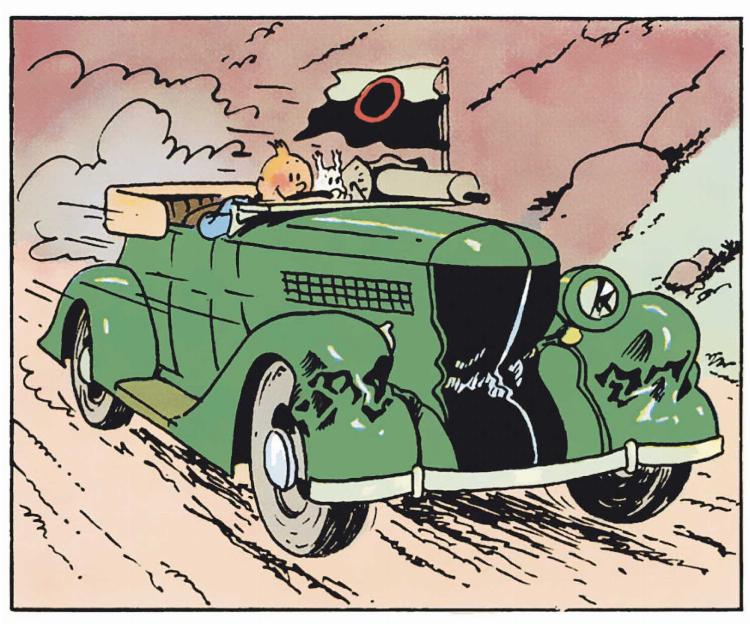

Desperate times call for desperate measures: Tintin occasionally resorts to military vehicles. In The Blue Lotus, he uses a Japanese armored car to escape from Shanghai. In The Broken Ear, he drives a 1936 Ford V8 convertible (Series 68 Deluxe), converted into a combat vehicle and equipped with a machine gun. Hergé was inspired by an advertisement published in La Revue Ford.

The tank used in The Calculus Affair is perhaps the most extreme example of this narrative logic—it becomes a tool of distraction, laced with a touch of, dare we say, absurdist humor.

Real, Modeled, or Invented Vehicles

One of the most fascinating aspects of Hergé’s approach to automobiles lies in the meticulous way he documented and depicted them. A striking example is the Ford V8, whose drawing he based directly on a manufacturer’s catalog from the years 1937–1939. This type of reference material, widely used by Hergé, allowed him to observe vehicle interiors in great detail. In one iconic scene where Tintin finds himself in the back of a taxi, Hergé drew inspiration from a photo of a Ford’s rear seating, giving the image remarkable authenticity.

But the Ford V8 is notable for more than just its looks—it also represents a significant technological leap. In 1932, Ford began equipping its standard models with the first mass-produced V8 engine: a compact eight-cylinder engine arranged in a V shape. Previously reserved for luxury cars, the V8 became a symbol of power, reliability, and efficiency. These technical strengths help explain the model’s popularity in Tintin’s action scenes, where speed and durability are essential.

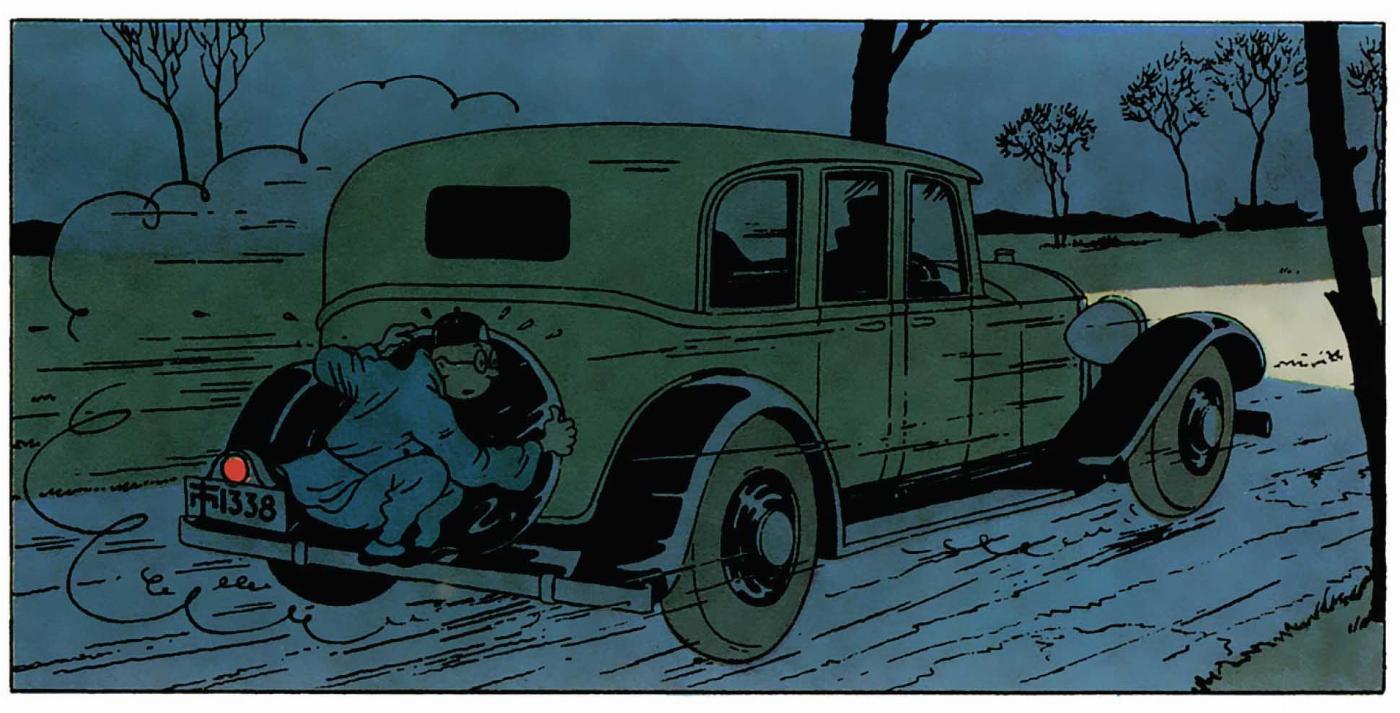

Another notable case is Mitsuhirato’s sedan in The Blue Lotus. Unlike other easily identifiable vehicles, this one belongs to the archetype of the 1930s American car. It can’t be pinned down to a specific make, but shares features common to Chevrolet, Nash, Ford, and Dodge models of the time. Its rounded lines, elongated trunk, high-mounted fenders, and spoked wheels are all visual elements that pay tribute to the era, without tying the drawing to a single real-world vehicle.

This “mystery car” also carries narrative weight: it appears in a tense moment when Tintin’s life is on the line. As a passenger alongside Mitsuhirato, he finds himself in a dangerous, confined situation. The car becomes a space of entrapment and suspense—further emphasized by its lack of clear identification, which amplifies the anonymity of the threat.

In his quest for narrative credibility, Hergé often turned to real-life models: Opel Olympia, Triumph Herald, Packard, Lincoln Zephyr, Cadillac Fleetwood (1937), Bugatti Types 35 and 52, Land Rover Series III, Checker Taxi, Messerschmitt, DKW, Isetta, Facel Vega HK500, the Soviet ZIL, Mercedes 600, Alfa Romeo Giulietta. Each of these models was carefully selected to reflect a character’s identity or a particular social or historical context.

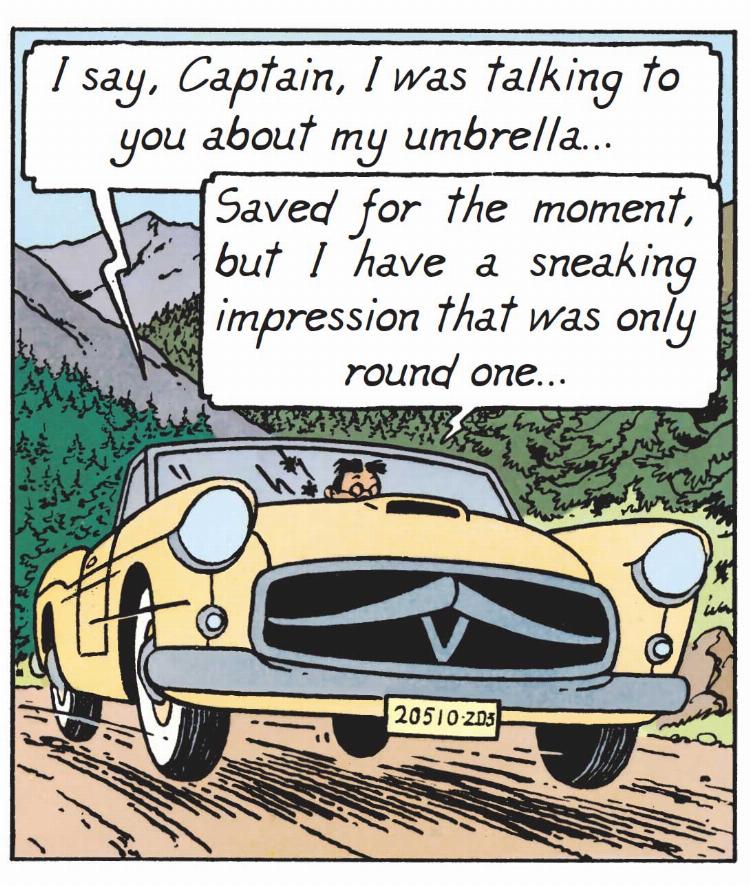

Some cars are iconic: Captain Haddock’s Lincoln Zephyr, for example, symbolizes his shift toward a more comfortable, bourgeois lifestyle (see article "The Speaking Vignette"). Other vehicles were entirely invented. The convertible associated with Plekszy-Gladz—with its moustache-shaped grille—was inspired by the Mercedes 220 SE and various French models. And remember Tapioca’s imposing black limousine? It’s a hybrid of the 1960s Mercedes 600 and the Soviet ZIL—an unmistakable caricature of dictatorial power.

In Cigars of the Pharaoh, the Lincoln Torpedo—a majestic blue convertible driven by Tintin—seems lifted straight from a 1930s advertisement. It was inspired by a model custom-built by Jacques Saoutchik. Inspired, yes—but not copied exactly.

Utility Vehicles, Trucks, and Caravans

Hergé’s albums are filled with deliberate inspirations drawn from real-world automotive design. One example is the red truck that rescues Tintin in The Blue Lotus, which may have been inspired by a Belgian Miesse truck from 1933—built by a manufacturer that also transported Auguste Piccard on scientific expeditions. The Eccles caravan in The Black Island, towed by a Triumph Herald, was drawn with remarkable precision by Bob de Moor, based on reference materials provided by Hergé.

A meticulous and loyal collaborator, Bob de Moor played a central role in modernizing several albums, particularly during the 1965 overhaul of The Black Island. Acting on Hergé’s instructions, he traveled to the United Kingdom with notebook in hand, carefully recording the car models visible in the landscape. Thanks to his efforts, Hergé was able to replace outdated or vague vehicles with realistic, contemporary ones based on catalogues and photographic references. Bob de Moor’s attention to detail helped reinforce the mechanical realism of Tintin’s world, while preserving the visual clarity of the ligne claire style.

Paradoxically, and despite their widespread popularity in real life, some cars make only fleeting appearances in Hergé’s universe. The 2CV, the Citroën DS, and the Volkswagen Beetle are seen merely in passing or in background crowds. On the other hand, vehicles like Citroën’s Ami 6, the Dupondts’ Peugeot 403, and the Jaguar Mark X do appear with a more defined presence.

Conclusion

The narrative cycle that begins with The Calculus Affair and ends with Tintin and the Picaros marks a clear shift: fewer conquests, more introspection. Tintin and Haddock become passengers in a world that increasingly escapes their control. Automobiles, in this context, become symbols—of absurdity, authoritarian power, or societal obstacles.

Hergé also uses cars as a vehicle for irony: in The Calculus Affair, a tree is flattened, a Mercedes convertible crashes through a wall, and an Alfa Romeo or BMW tears across a manicured lawn. This mechanical mayhem serves as a critical and comic climax in several albums.

The automobile in Hergé’s work is never incidental. It is at once a driver of action, a social mirror, and a tool of satirical commentary. Every model featured in the albums—whether real, imagined, or entirely invented—reflects the care and precision of an author deeply engaged with his time. Each vehicle, from the most luxurious to the humblest, becomes a silent yet eloquent witness to the adventures of the reporter with the iconic quiff.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books