A Lunar Project: Tintin's rocket

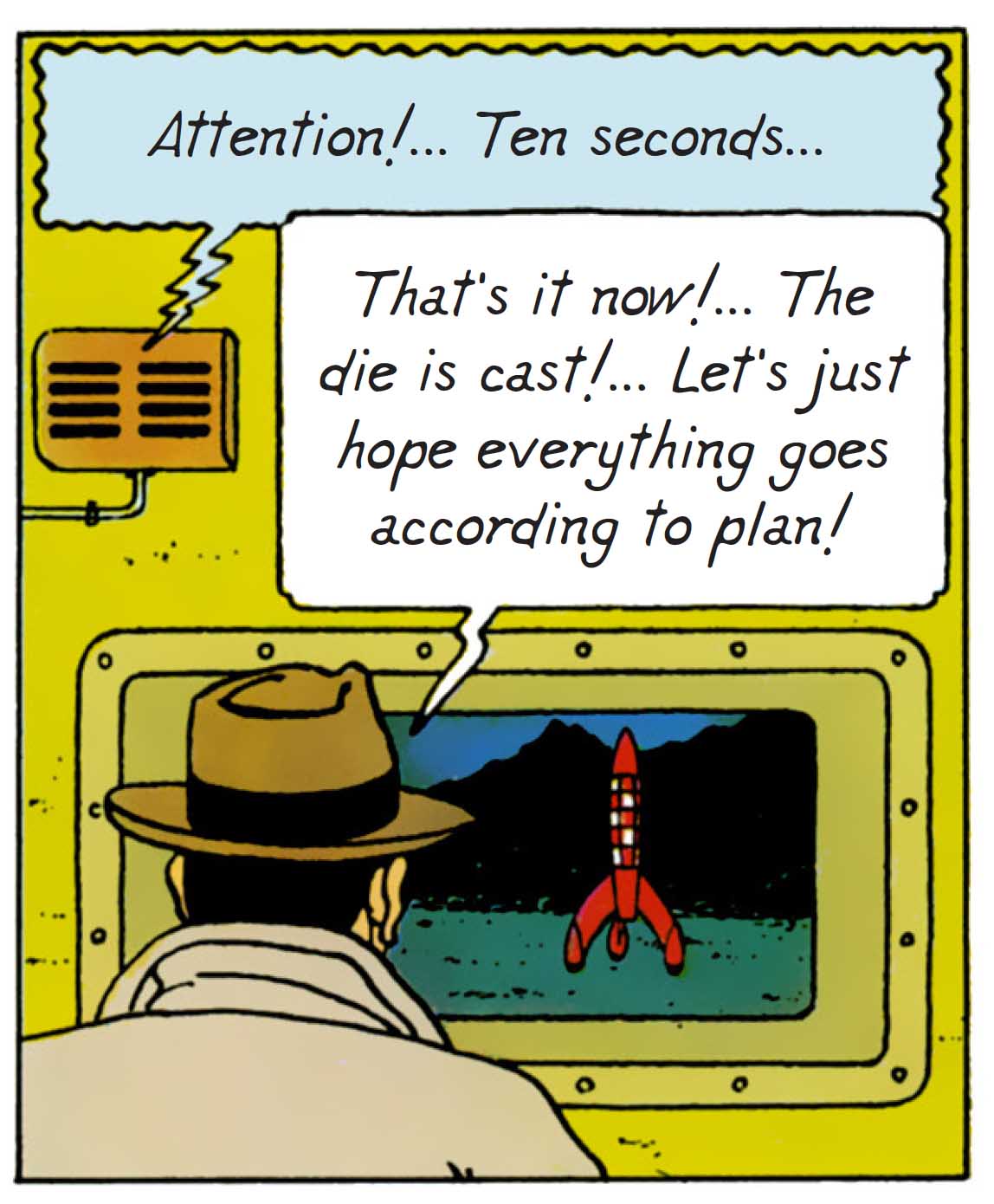

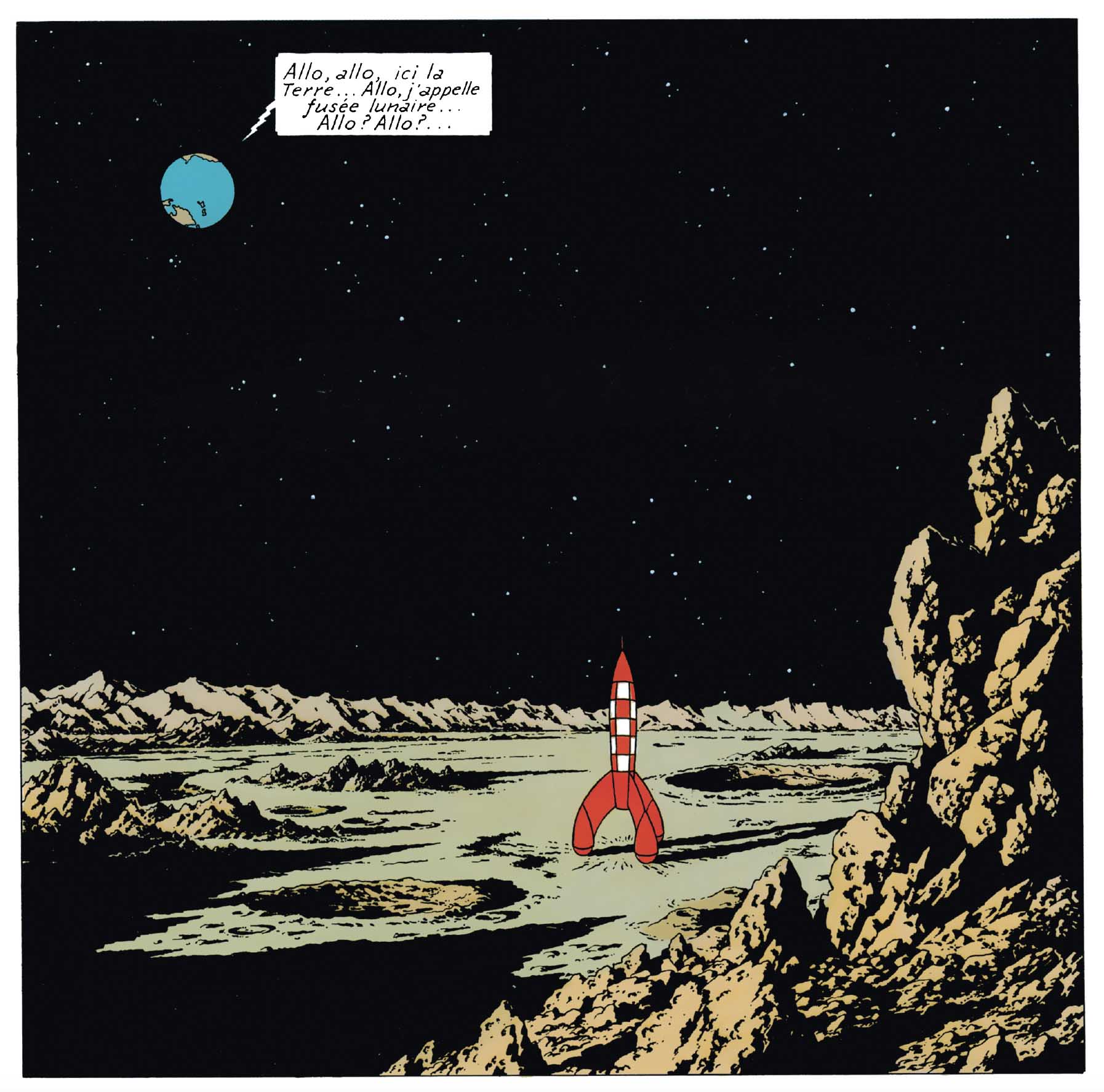

As famous as Tintin himself, the red-and-white rocket has become an unforgettable visual symbol — a lifelike icon etched into the collective imagination.

Before liftoff, doubts had to be faced, failed scripts abandoned, and deep skepticism overcome. Nothing was set in stone: the project wavered, stumbled, lacked confidence. And yet...

In 1947, Hergé received a first script titled Tintin on the Moon, co-written by Jacques Van Melkebeke and Bernard Heuvelmans. The story, inspired by the American vision of space exploration (with rocket designs borrowed from bases like White Sands), failed to convince him. Hergé quickly shelved the idea, unsure of his ability to depict such a scientific world — and, more importantly, uneasy with the tone of the story. The project stalled before it even started.

Encouraged by Raymond Leblanc to continue with the lunar theme, Hergé chose an entirely new approach: he imagined a Syldavian space mission — neutral, fictional, and free from real-world geopolitical tensions. From the original script, he retained only a few visual and comic ideas. The story became a completely new creation.

The pieces finally fell into place, concrete ideas began to take shape, and the research took a whole new direction!

Hergé Before Sputnik

When Hergé began Destination Moon in March 1950, the sky still belonged to the realm of human imagination — fanciful, but fertile. The ambitious idea of flying into the heavens dates back concretely to Antiquity, embodied in the now-famous myth of Icarus. But this time, there would be no burning wings. Humanity had yet to launch a single object beyond Earth’s atmosphere. Only one German rocket, the A4-V2, had grazed the edge of space in 1942, reaching an altitude of 85 kilometers from the Peenemünde site.

Yet in the hushed calm of his Brussels studio, Hergé was already imagining a manned mission to the Moon: a colossal rocket, nearly 75 meters tall, monobloc, capable of launching in a single burst, maneuvering in orbit, landing gently on the lunar surface, and returning intact to Earth. This vision came nine years before Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin's first manned spaceflight, and fifteen years before the Apollo 11 mission. A bold anticipation — one that commands respect. Hergé didn’t just get ahead of his time; he sketched it out in clear ink, with a precision that almost makes one forget it all began as “just” a comic book.

A Close Collaboration

The turning point in this project is built upon a book published in March 1950: L’Astronautique by Alexandre Ananoff. This work became the scientific foundation of the story. In it, Hergé found data on rockets, the effects of gravity, propulsion systems, temperature, space suits, and even the risks posed by meteorites.

To push his research even further, Hergé visited the ACEC, Belgium’s nuclear research center, thanks to Max Hoyaux — a scientist who informed him of the possible presence of an ice layer on the Moon’s surface. That detail didn’t fall on deaf ears: Tintin later shouts “Yikes!... Ice!” at the bottom of a lunar crevasse while searching for Snowy.

He also relied on the expert advice of Bernard Heuvelmans to accurately depict the inner workings of an atomic research center. However, Hergé’s sources of inspiration weren’t limited to academic or scientific ones. Visual references came as well from films like Destination Moon (1950), and from illustrated magazines such as Strange Adventures. The references are many — and so are the gags!

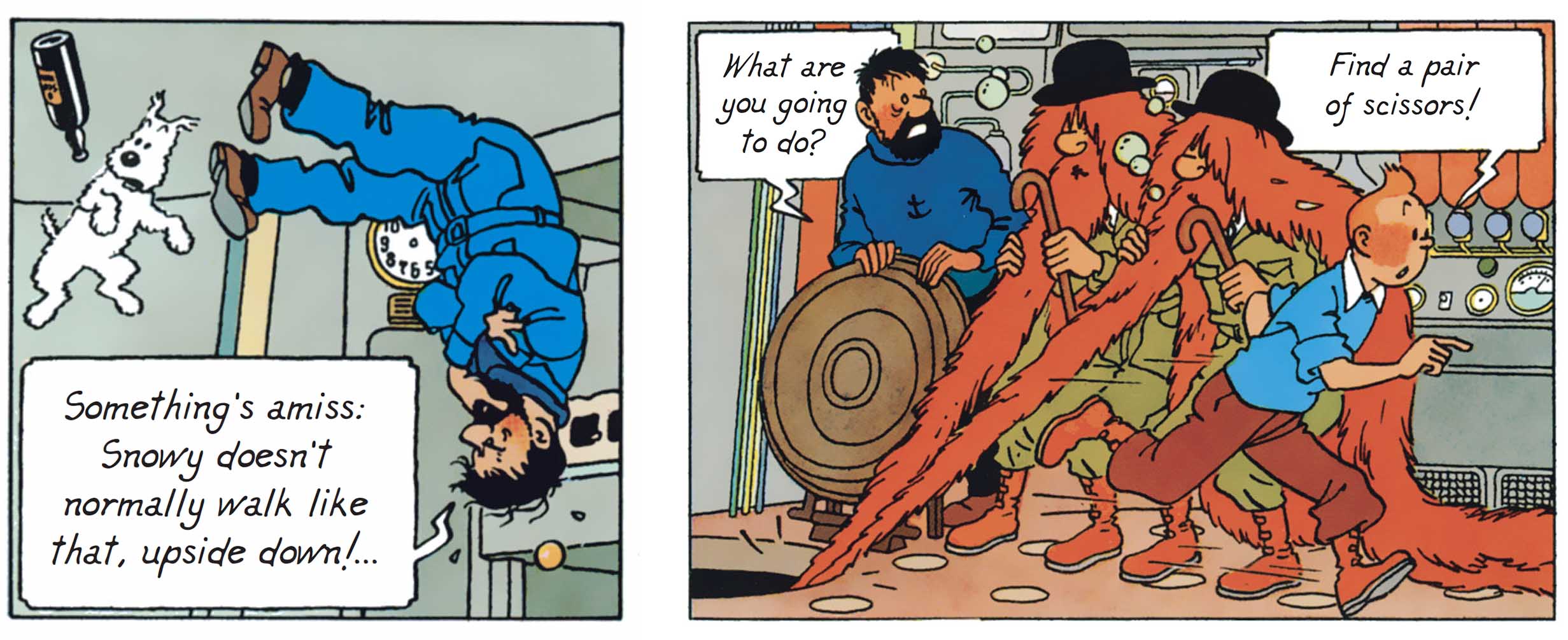

Adventure with no Gravity

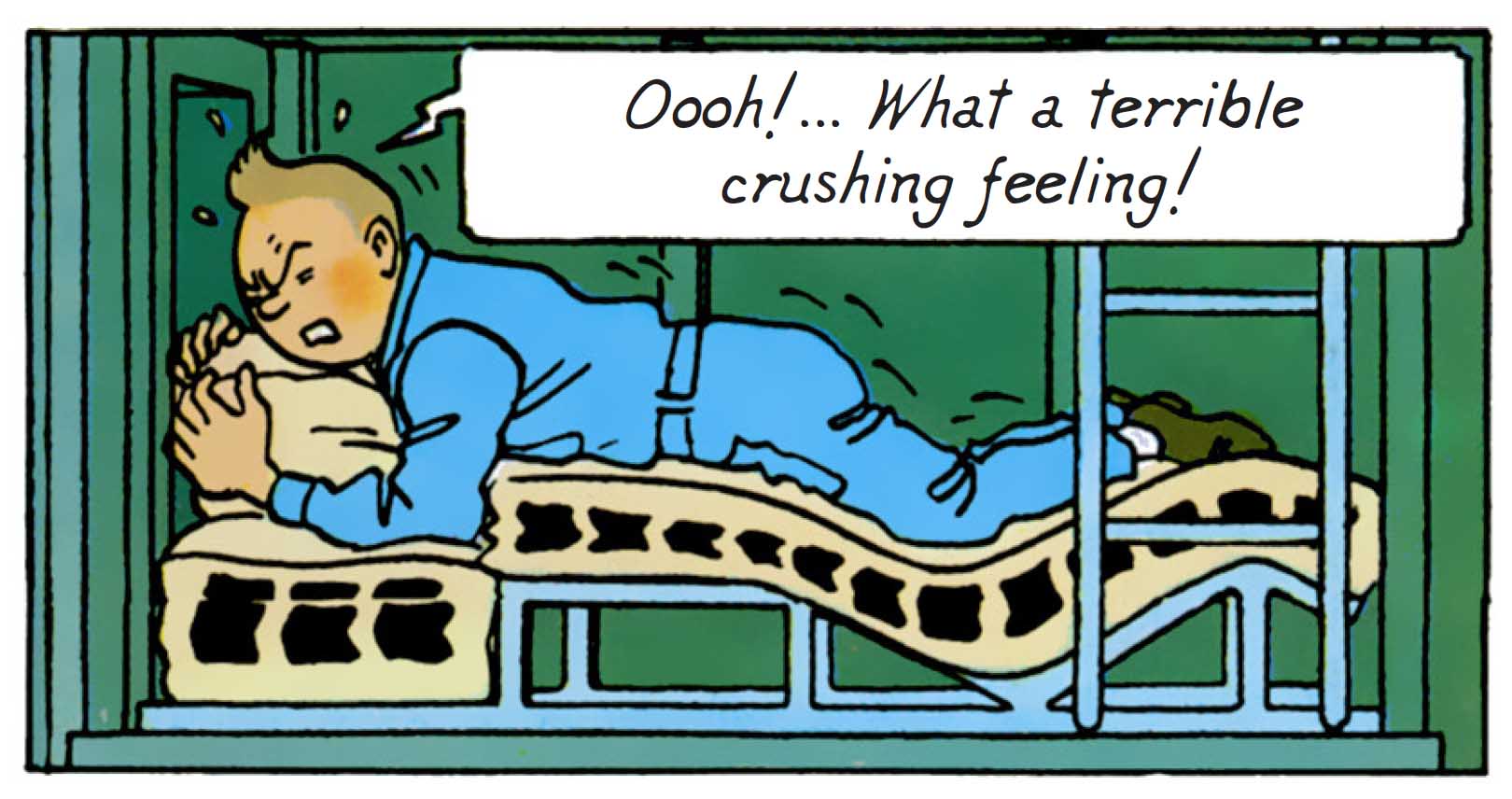

The journey is scientific, but also profoundly human in its mishaps: Haddock loses his temper, the Thom(p)sons turn all the colors of the rainbow (see Land of Black Gold), and Professor Calculus hears little to nothing — a recurring trait perfect for raising tempers. Even the pressurized "chamber," equipped with reclined seats to withstand acceleration (a configuration borrowed from fighter pilots and suggested by Ananoff), becomes a scene of physical comedy.

But let these cascading blunders not obscure the forest of originality and inventiveness in the story. Some of Hergé’s insights would later be confirmed — like untethered spacewalks (Haddock precedes Bruce McCandless by thirty-four years) or the importance of the center of gravity during lunar landing. Others remain unattainable, such as the descent beneath a cloud of dust in the Moon’s vacuum.

But no matter. What Hergé depicts, anticipates, and scripts in his fiction is not the conquest of the Moon as a military or scientific victory, but the invention of a new kind of space - narrative, moral, almost philosophical — where technology becomes set design, discipline becomes language, and the red-and-white rocket stands as a totem of restrained humanity. The modern Icarus has donned his finest attire to avoid an untimely roasting. In just two albums, Hergé works wonders, distilling a mass of technical jargon into something the common reader can follow — and enjoy.

A Unique Rocket

If its shape is easy on the eyes, its core overflows with knowledge and ideas — like a brilliant mechanism concealed beneath a veneer of simplicity. Tournesol’s rocket, born of painstaking research, is a feat of imagination. Monobloc and fully reusable, it operates on the principle of continuous acceleration via a nuclear engine.

To contain the heat from this reactor, Tournesol invents a fictional alloy: Calculite. Don’t bother checking the dictionary — this neologism neatly sidesteps many of the technical constraints of Hergé’s time.

Liquid hydrogen, heated to over 2400°C, serves as the propellant. This main engine is backed by an auxiliary chemical engine, used during launch and landing to avoid contaminating Earth’s atmosphere. The structure is meticulously conceived, down to the smallest detail: stabilizing fins, a telescopic landing gear, and a lowered center of gravity.

The interior includes a cockpit inspired by technical drawings annotated by Ananoff, reclining seats to endure critical phases of acceleration, and a pressurized “chamber” equipped for the crew. Hergé faithfully transposes real-world physical constraints into his drawn universe. According to the schematics seen in the albums, the rocket would stand nearly 75 meters tall — far more than the 50 meters claimed.

If the albums avoid triumphalist rhetoric, it’s not due to naïveté, but a deliberate choice. Tournesol’s rocket belongs to no nation, but to Syldavia — a fictional, deliberately neutral country. Where Armstrong would plant a flag, Tintin plants none. He leaves a message in the name of science and exploration. The care devoted to the craft reflects this pacified ambition.

Though inspired in form by the German V2 rockets, the X-FLR 6 and its larger lunar successor soon diverge from that model. V2s were built to strike; Hergé’s rockets are built to return. The chemical propellants mentioned (nitric acid, aniline, liquid hydrogen) were plausible for the time — as was the concept of a nuclear engine powered by heated hydrogen. These ideas, credible in 1950, would later be abandoned for reasons of cost and safety.

Hergé doesn’t invent so much as curate — assembling and streamlining real-world concepts to integrate them more effectively into his narrative. And everything goes according to plan — even if one or two spies try to slow the heroes down.

Realism and Incongruities

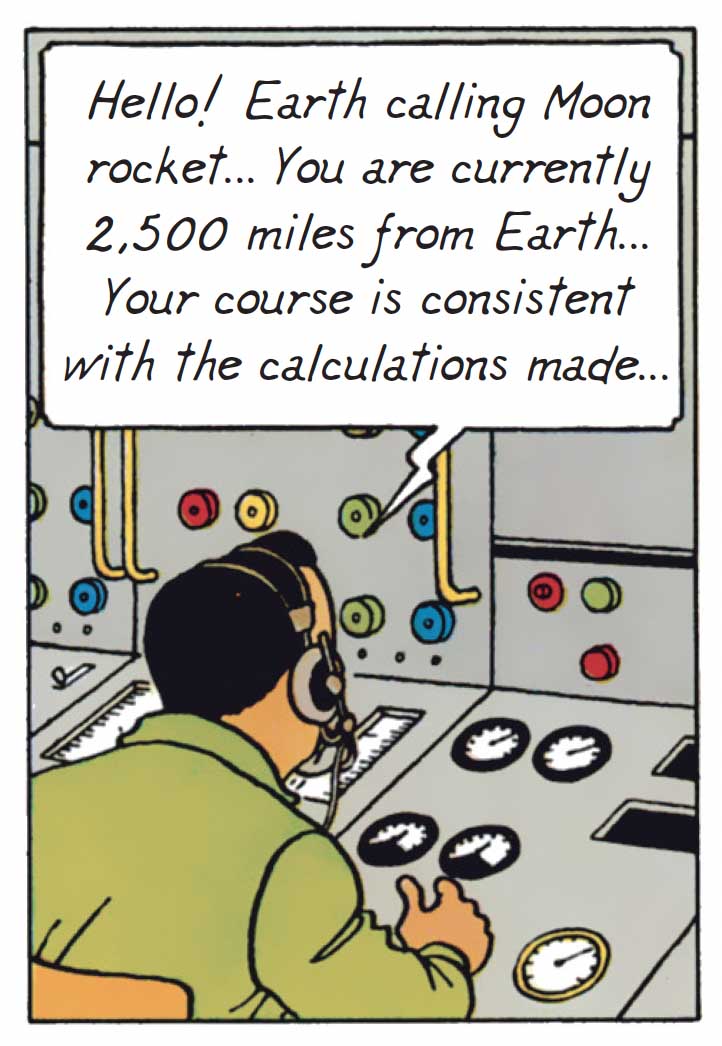

Some choices stem from technical precision, others from narrative freedom. Hergé imagines a journey from Earth to the Moon completed in four hours at 45 km/s — far faster than the Apollo missions. This isn’t a mistake, but a deliberate choice for storytelling efficiency. Similarly, the rocket’s descent beneath a cloud of lunar dust — physically impossible in the Moon’s vacuum — offers a strong, dramatic image.

The album also presents unexpected scenarios, such as the difficulty of managing oxygen — a central issue in the second volume. Wolff’s sacrifice marks the emotional high point of this subplot. Hergé does not aim to deliver a science lesson, but to render a human adventure believable within a scientific framework. Inaccuracies become narrative choices. What matters isn’t technical accuracy, but internal coherence — the balance between tension, comedy, and anticipation. And it’s precisely this balance that gives the whole work its timeless quality. After all, lunar gravity is no laughing matter — especially when it makes you lose a bottle of whisky!

Still, all this orbital chaos unfolds under the guidance of an astonishing array of verifications, maintaining plausibility and preserving that crucial suspension of disbelief. Because everything in this adventure is governed by one overriding principle: control.

To Infinity... and Beyond Comics!

Ultimately, this red-and-white rocket becomes a character in its own right. No real-world vehicle resembles it, and yet it is instantly recognizable. Its sleek silhouette, geometric checkerboard pattern, and curved fins make it a perfect graphic object — a totem of mastered science. It transcends the boundaries of the comic book to become a universal emblem, reproduced on posters, turned into toys, adapted into countless forms — and even admired as far away as Japan. You’ll find it in shop windows and museums, in designer interiors and children’s bedrooms alike.

Even Hergé himself was surprised — he had conceived it with documentary rigor, drawing from the work of Ananoff and the technical models of his time. What was meant to be just a paper craft in service of a story took on a visual autonomy and a life of its own. It became more than a narrative vehicle: a cultural icon, a fragment of technical utopia, a synthesis of childhood, precision, and imagination. The rocket didn’t just take Tintin to the Moon — it launched an entire branch of comic art into a modern, adult, and inexhaustible imaginary world.

And now it's your turn to play...

Test your knowledge with this rocket quiz.

Good luck!

« Tintin's rocket »

9 questions

9 questions

« Tintin's rocket »

What is the name of the professor who designs the lunar rocket?

Baxster

Calculus

Wolff

« Tintin's rocket »

What does Captain Haddock do that nearly causes an accident aboard the rocket?

He plays with the navigation controls

He tries to smoke his pipe

He activates the main engine

« Tintin's rocket »

What gas is used to power the rocket?

Methane

Pure oxygen

Liquid hydrogen

« Tintin's rocket »

What altitude did the German V2 rocket reach, as mentioned in the album?

50 km

70 km

85 km

« Tintin's rocket »

What causes a series of comical mishaps in zero gravity aboard the rocket?

Captain Haddock trying to drink whisky

A malfunction in the engine

Snowy floating with a bone

« Tintin's rocket »

What is the approximate height of the rocket according to the plans?

50 meters

65 meters

75 meters

« Tintin's rocket »

What fictional material is invented to withstand the rocket's heat?

Syldavite

Calculite

Hergeium

« Tintin's rocket »

What maneuver does the rocket perform before landing on the Moon?

It rotates 180°

It deploys a parachute

It separates a landing module

« Tintin's rocket »

How long does the rocket take to reach the Moon in the album?

Three days

Forty-eight hours

Four hours

« Tintin's rocket »

Your score:

Texts and pcitures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books