The Speaking Vignette: Tintin's rocket

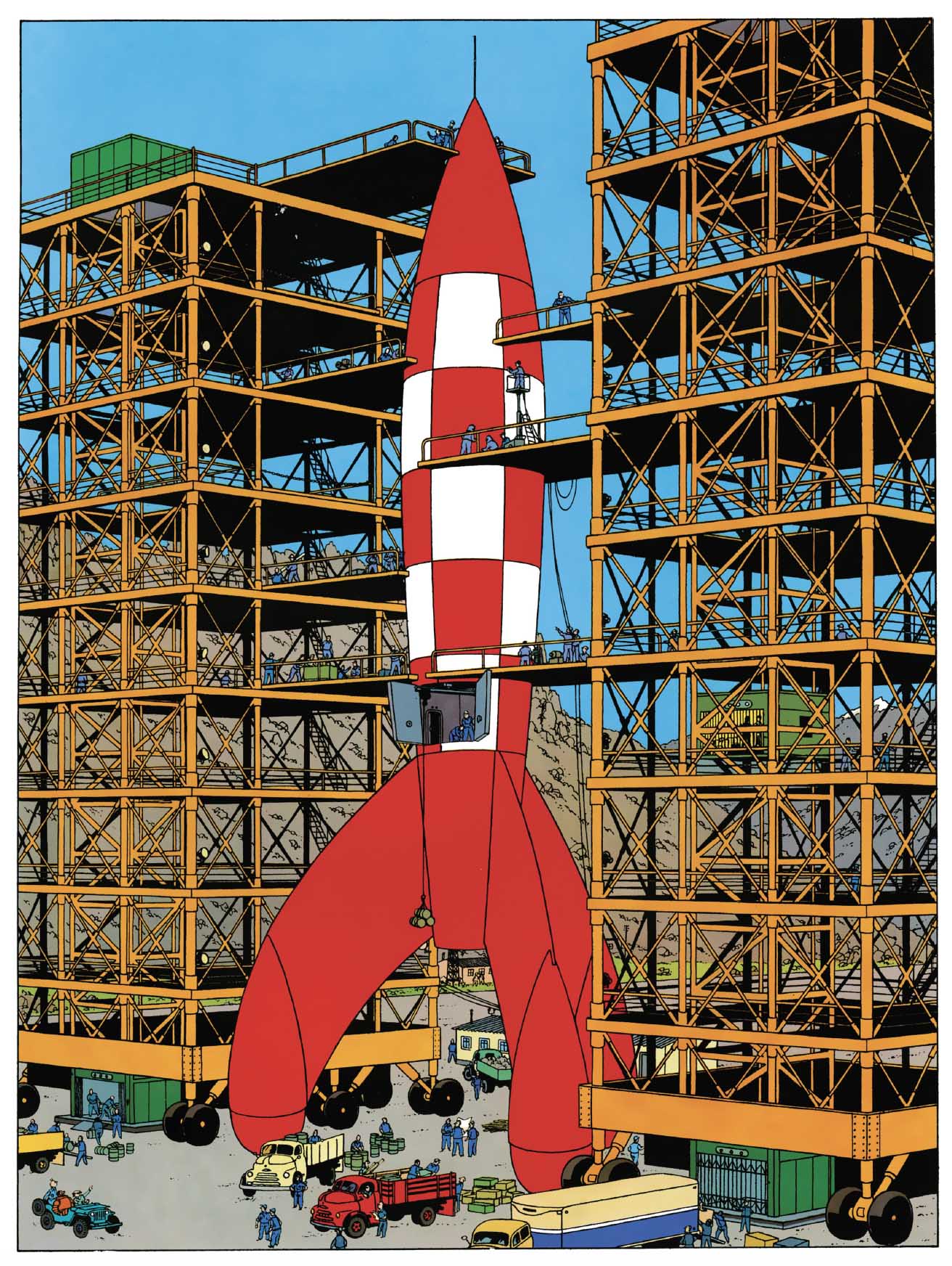

In this now-iconic vertical vignette, the star of the Syldavian lunar program prepares to pierce an inky sky, trailing a dense exhaust plume. Every reader recognizes it instantly - because it has become THE definitive symbol of Francophone science fiction.

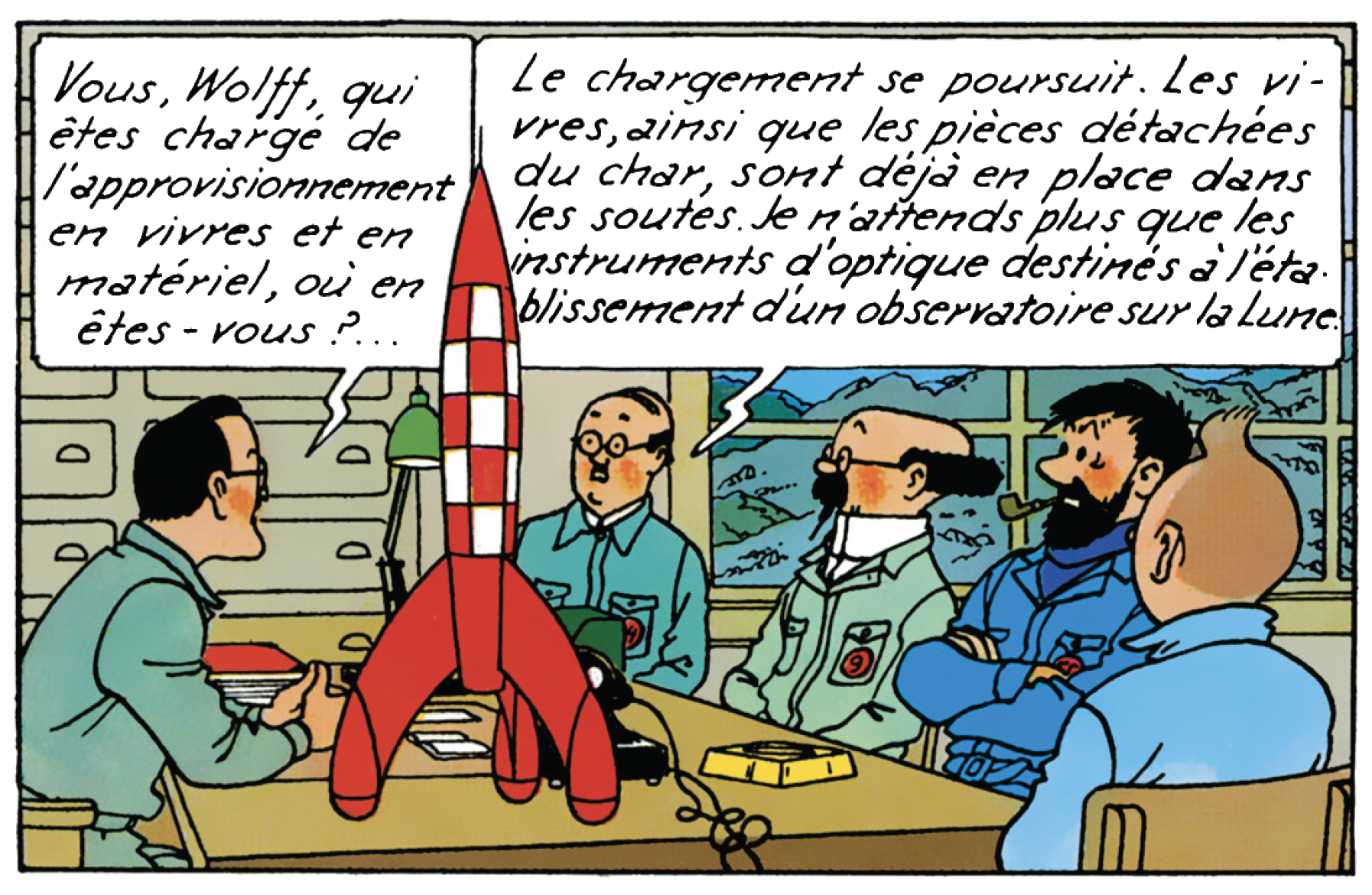

Amid a humming hive of activity, where technicians scurry and engineers prepare, it stands upright, silent and sovereign. Perched on its launch pad, the rocket is no mere invention - it is the culmination of a painstakingly constructed, documentary-based approach.

Hergé did not improvise this rocket.

From 1947 to 1950, he gathered sources, read voraciously, exchanged letters, and sought out visual references. Even before the launch of Sputnik, he was deeply interested in the nascent world of astronautics. One key resource was L’Astronautique by Alexandre Ananoff, a scientific popularization manual, but he also drew heavily on visual sources from international technical magazines.

The rocket’s tapered profile, with its elongated nose cone, clearly echoes the model built for Fritz Lang’s 1929 film Woman in the Moon. The influence of German science fiction cinema, intertwined with the imagery of early ballistic research, helped establish an aesthetic that was both futuristic and credible.

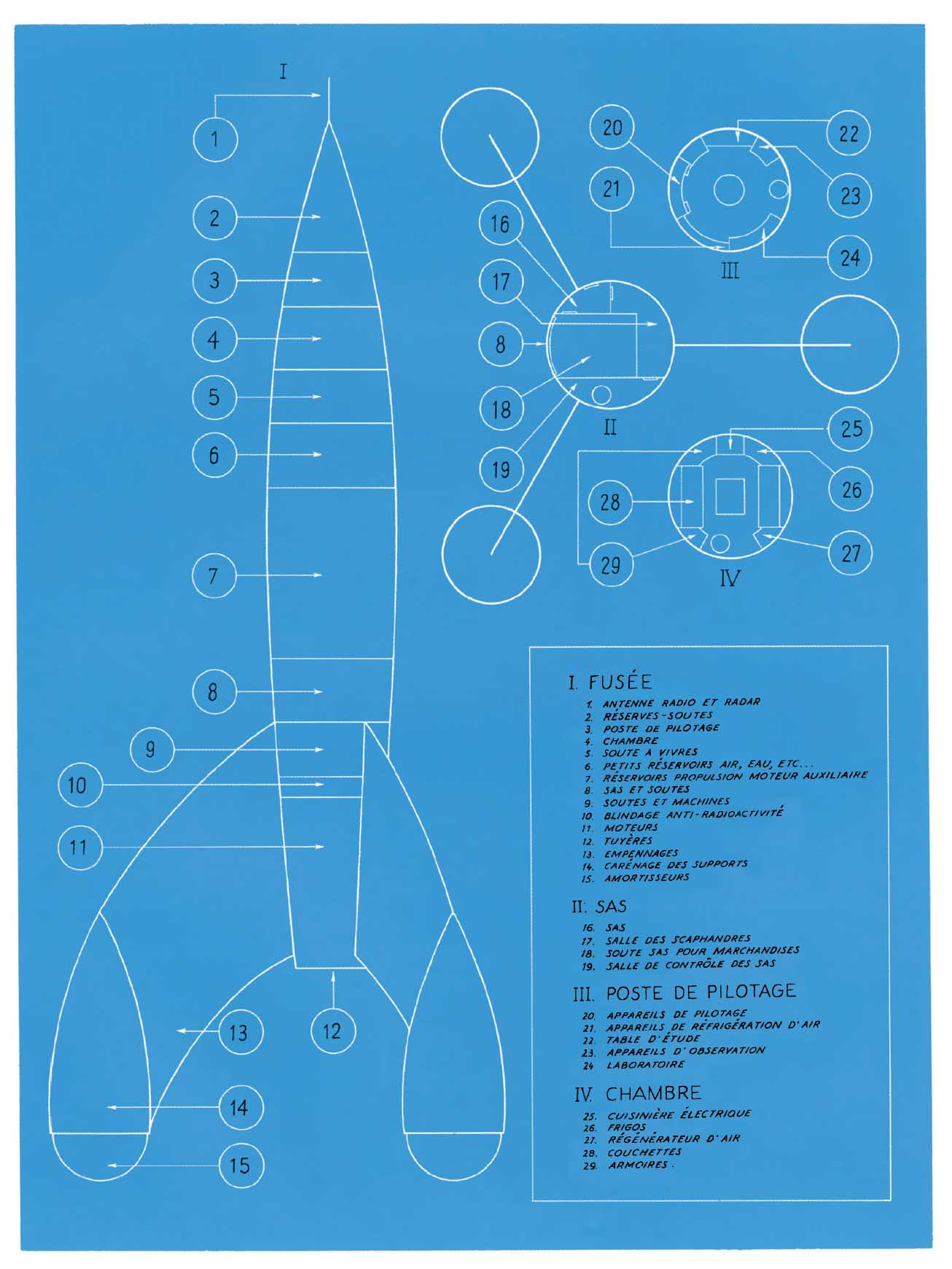

Its internal structure, outlined in some of the album’s schematic pages, also bears a strong resemblance to prototypes from engineers like Johannes Winkler, who, in the 1930s, tested liquid-fueled rockets with vertically stacked tanks and compartmentalized engineering—compact, rational, and forward-looking.

Further details reveal Hergé’s attentiveness to cutting-edge science. He subtly incorporated references to postwar American projects. The WAC Corporal, the first sounding rocket developed by the United States, lent inspiration through its sleek form and slim profile.

All these influences converge in this image: the rocket is single-stage, reusable, and powered by a fictional - but scientifically plausible - nuclear propulsion system. Hergé imagined a plutonium core heating liquid hydrogen, a speculative concept rooted in actual research, particularly the U.S. NERVA project.

Its overall height, estimated at 75 meters based on the album’s internal diagrams, matches real-world rocket proportions. The oversized fins ensure directional stability, while the red-and-white checkerboard pattern - visually borrowed from test versions of Germany’s V2 rockets - becomes, here, the visual emblem of Syldavia.

With this image, Hergé doesn’t just illustrate a flight to the Moon. He envisions a possible, plausible, nearly tangible future. And with the stroke of a pen, he transforms comic art into a manifesto for space travel. A bold projection of what might come - drawn from the present of a Belgian artist in the early 1950s.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books