The Gothic Architecture in The Adventures of Tintin

The Adventures of Tintin transport us to a reality shrouded in mystery, History and the charm

of discovery. To ensure maximum accuracy, Hergé devoted himself to studying mechanics,

aeronautics and technological innovations, which, among other achievements, enabled Humanity to

reach the moon.

However, there is a series of adventures inspired by historical monuments and events, which

give weight and substance to the narrative. These include: the discovery of a mysterious group of

smugglers operating in an archaeological site in Egypt, in Cigars of the Pharaoh; the search for an

ancient South American artefact stolen from the Ethnographic Museum in The Broken Ear; the

enigma of the crystal balls, which takes the heroes to the heart of Peru, a privileged place of the

Inca civilisation, in the albums The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun.

In addition to these albums, there are three adventures that fit into this context, but curiously,

their narrative is set on the European continent, the birthplace of Gothic architecture. King Ottokar’s

Sceptre, The Black Island, The Secret of the Unicorn, and Red Rakham’s Treasure are examples of how History and Architecture find parallels with mystery.

Through Craig Dhui Castle in Scotland, Kropow Castle in Syldavia, and the underground passages of Marlinspike Hall in Belgium, mysteries are revealed, as if the past held the key to the solution. All these monuments have in

common the Gothic style, presented in their different elements and characteristic structures. Perhaps Hergé wanted to reach a distant medieval past, giving historical weight to the adventures and objects that these places reveal to us.

It is true that many of the artists who contributed to Hergé’s work had a predilection for drawing medieval narratives and elements. One such case was Jaques Laudy, who claimed to be: “A valiant knight of the Middle Ages, born by mistake in the twentieth century…”

The Black Island

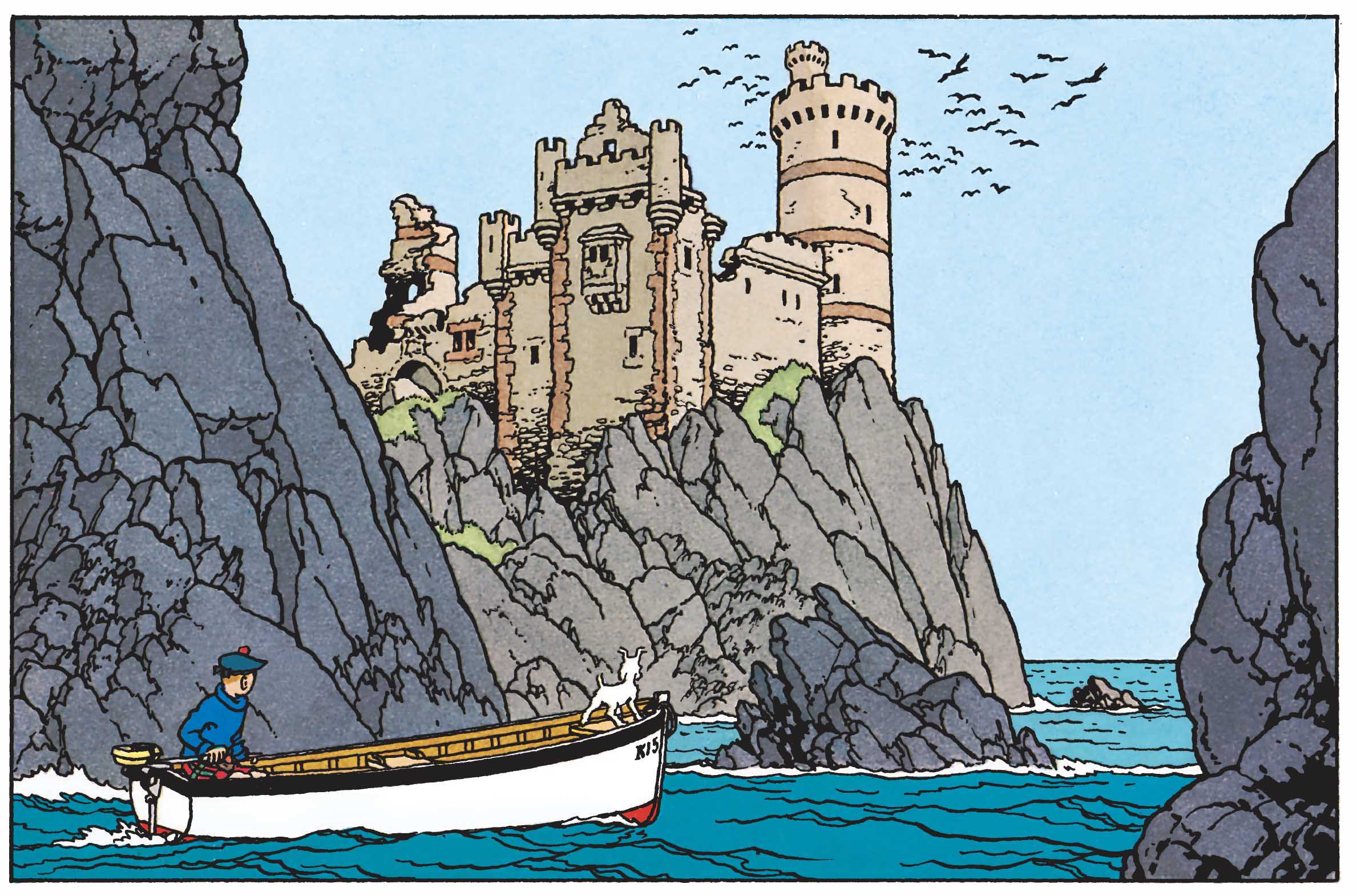

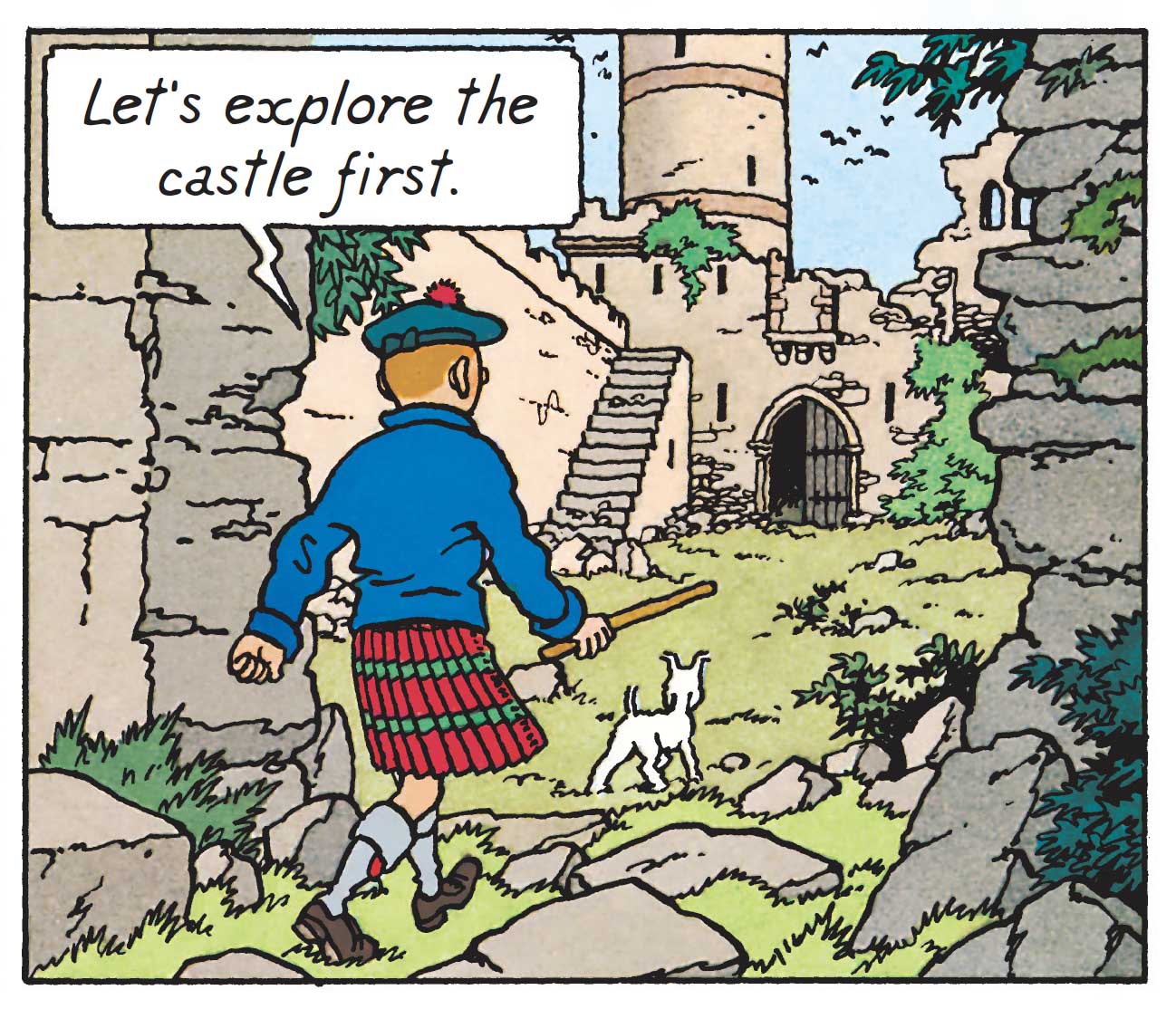

The Black Island, an adventure originally published between 1937 and 1938, introduces us to Craig Dhui Castle, located on a deserted island in the seas of Scotland. Many researchers have speculated on which monument may have inspired Hergé to design this castle, but we do not have enough reliable data to reach a definitive conclusion. The most widely accepted hypothesis is the Vieux-Chateau of Ile d’Yeu, built in the 14th century and located on the French Atlantic coast.

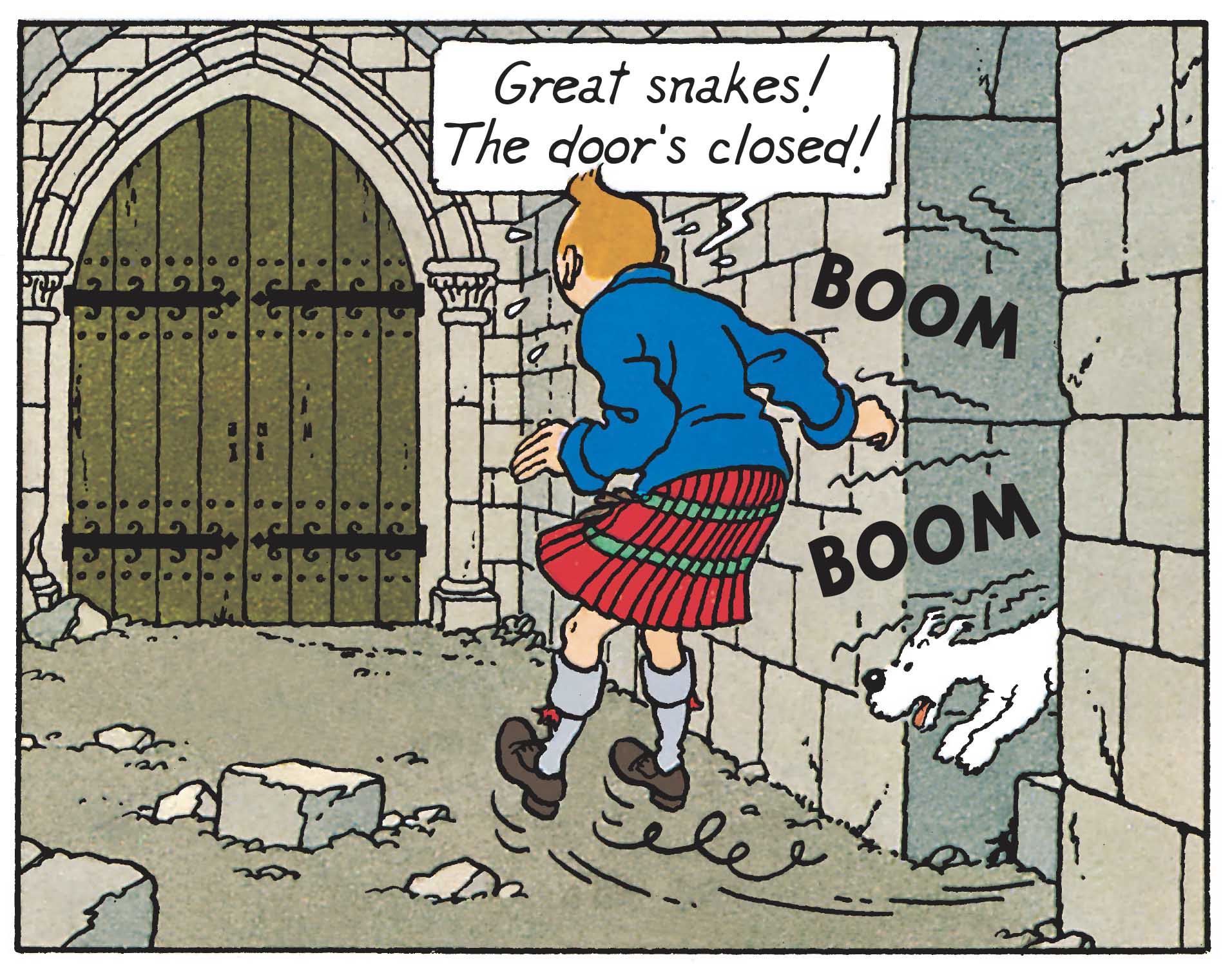

The structure of Craig Dhui Castle is defined by its defensive military architecture and corresponds to the appearance of several Scottish castles. The keep, spiral staircases, ogival portals and pointed arch bridge provide clues for dating the castle between the 13th and 15th centuries. The portal leading to the tower corresponds to a primitive Gothic design, which shares the Corinthian capitals of the portal leading to Kropow Castle. In fact, it was only from the 13th century onwards that Gothic style spread to military and defensive architecture, rather than being confined to purely religious buildings. In this example, Gothic architecture brings an aura of mystery that hangs over Black Island. We find the historical testimony of the monument in contrast to the modern counterfeiting of banknotes that was perpetrated inside it.

We must take into account the colour versions and the original black and white version of

this album. The 1938 and 1943 versions did not feature any Gothic elements, a detail that was only

added in the definitive publication, dated 1965.

Hergé travelled to the South of England in March of 1937, where he may have gathered

information for the creation of this narrative. With this in mind, we can hypothesise that he was

inspired by English monuments for the design of Craig Dhui Castle.

If we look at the original version, where the portals and windows have a round arch, we see traces of Northampton Castle, originally built in the 11th century. But let us focus on the 1965 version, which features the profusion of Gothic elements mentioned above. Windsor Castle corresponds to this type, with circular towers and ogival portals. Even Hergé refers to Windsor Castle in his unfinished album Tintin and Alph-Art. Although its construction began in the 11th century, from the 13th to the 16th century it underwent many modifications, with the introduction of Gothic elements, which associate this monument with one of the greatest examples of English Late Gothic architecture (Perpendicular Gothic). Arundel Castle is perhaps the closest example to Craig Dhui, with an identical circular keep and ogival windows. Its origins date back to the late 11th century, with subsequent interventions until it underwent extensive restoration in the 19th century.

In this context, we can assume that Craig Dhui Castle may be a stylised idea of a medieval English castle, which may have been altered in the 19th century. Its poor state of conservation suggests that it still preserves its original features, but the metal doors and subsequent alterations suggest otherwise. Therefore, this monument is a complex problem of influences.

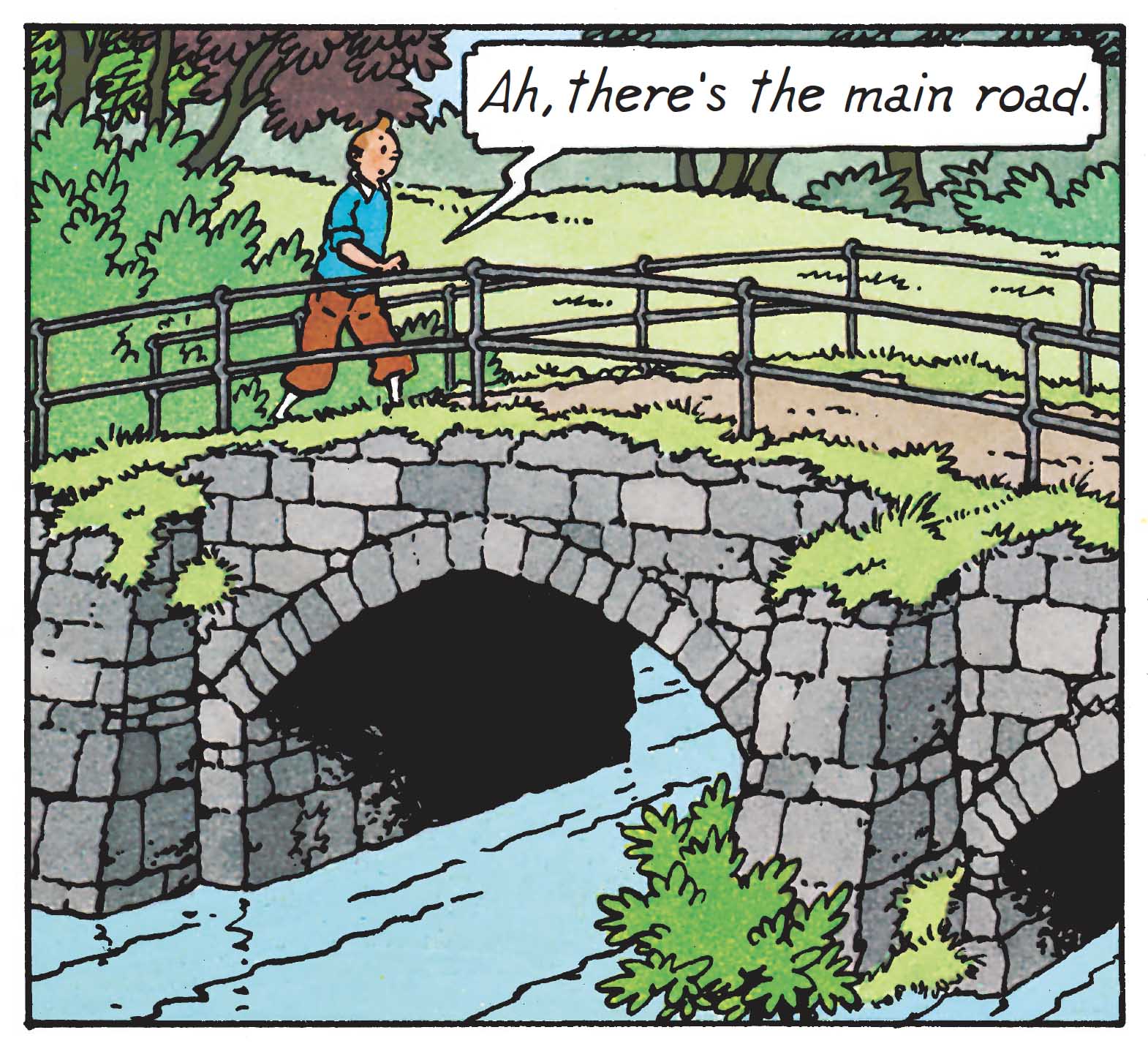

In addition to this Scottish Gothic monument, Tintin crosses a Gothic stone bridge when travelling from Dover to Sussex. There are several similar examples in southern England, but Gallox Bridge, located in Dunster and built in the 15th century, most closely resembles the one found in this album.

In the Sussex region, we enter Doctor Muller's mansion, directly inspired by a photograph of a Scottish country house that was in Hergé's archives. In this image, we see a late Gothic-inspired fireplace, which could have been designed between the late 18th and 19th centuries. This style is commonly referred to as Tudor, originating in the 16th century. This fireplace plays a crucial role, as it is through its fire that Tintin manages to untie himself, defeat Doctor Muller and escape from the mansion.

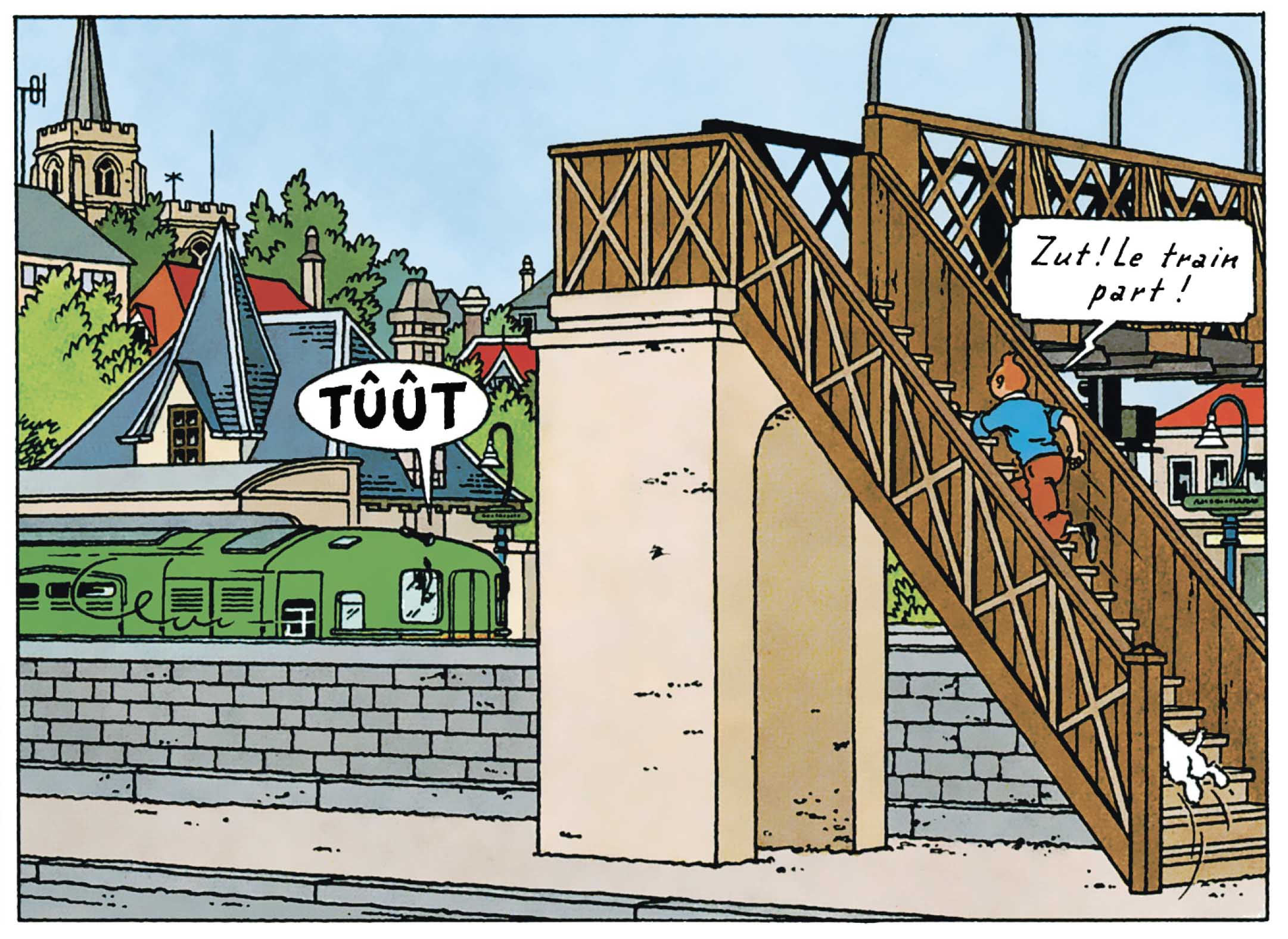

In the Sussex landscape, there is a Gothic church tower, whose characteristics are identical to Chichester Cathedral. Its tower is considered one of the tallest in England. Built between the 12th and 14th centuries, it underwent numerous modifications over the centuries and collapsed in 1861. Despite this, it is more likely that Hergé was inspired by the tower of St Michael's Church in Bishop's Stortford, built in the 15th century. The similarity leaves no room for doubt.

As Tintin himself said when he saw Craig Dhui Castle: ‘...It is a sinister place…’ The Gothic style is an element that contributed to this feeling of apprehension and mystery.

King Ottokar’s Sceptre

The album King Ottokar’s Sceptre was written and drawn between 1938 and 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, but it contains clues to understanding the political and military tension that was felt at that dark moment in History. Perhaps to divert readers’ attention from reality, Hergé created two countries fighting each other in the Balkans. On one side is Syldavia, a democratic kingdom that defends freedom and the free circulation of ideas. On the opposite side, we see Borduria, a dictatorial military republic ruled by an unscrupulous man who imposes censorship and martial law. Obviously, these characteristics remind us of several European

countries that were in this position.

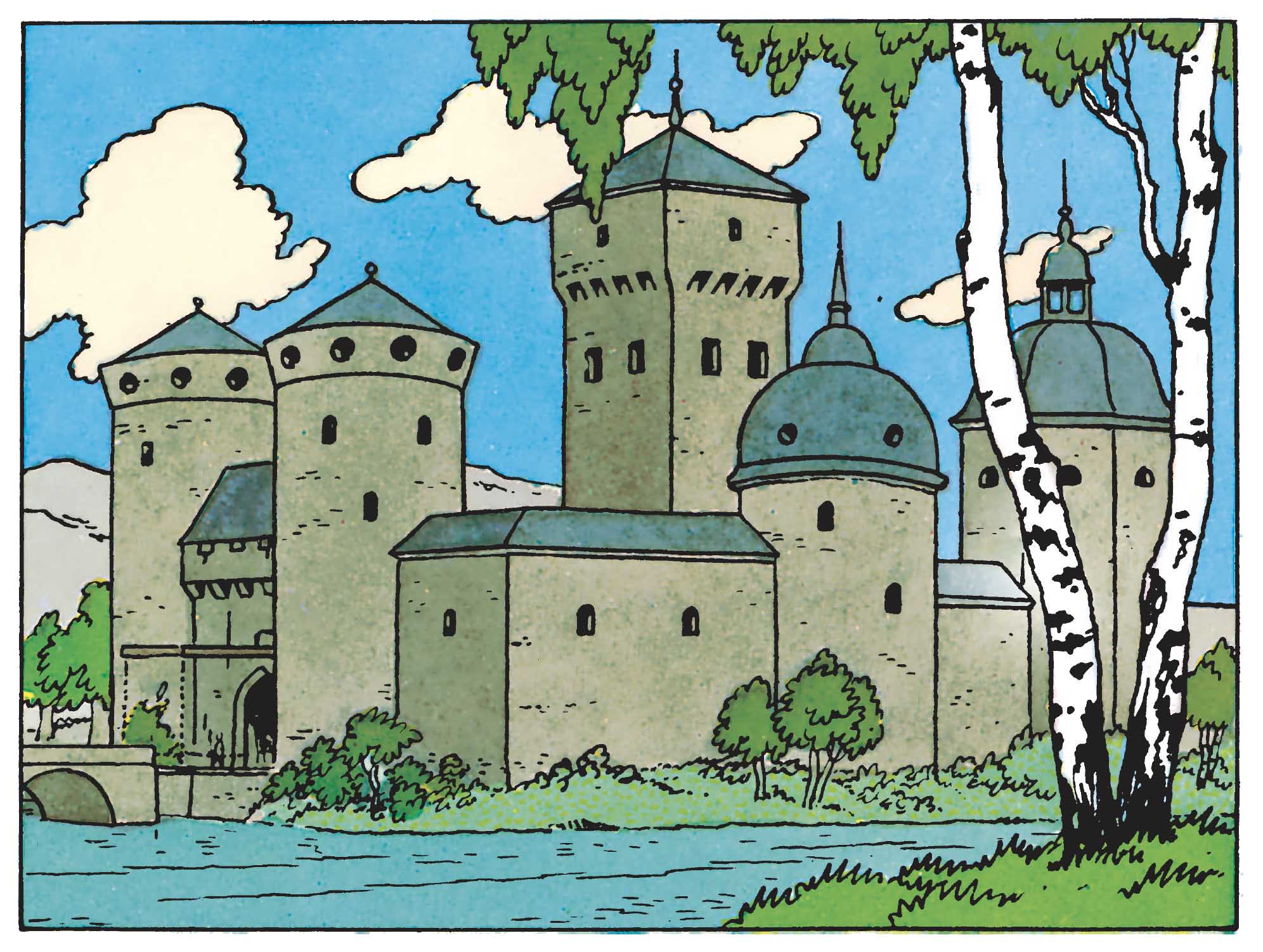

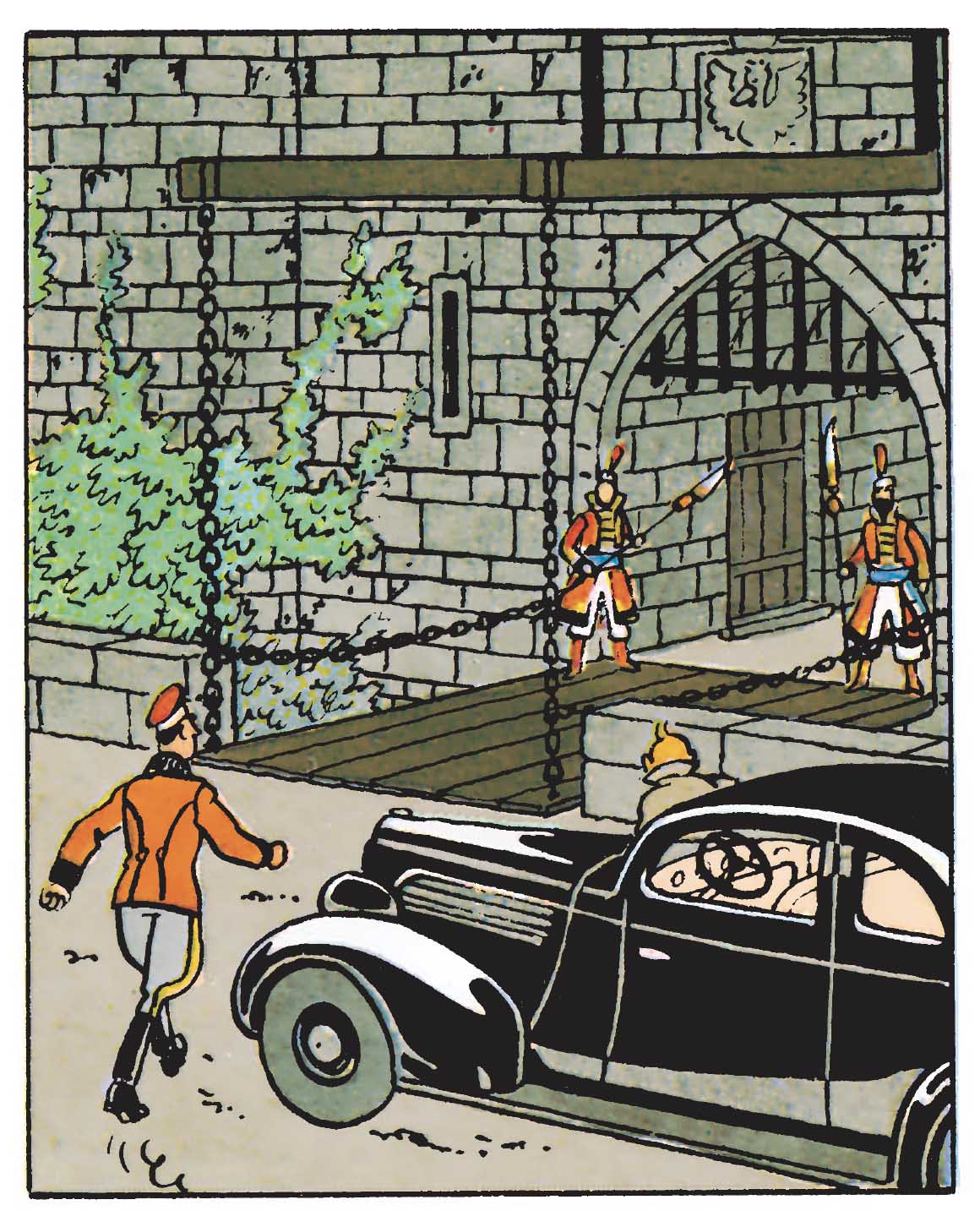

The bastion of Syldavia’s sovereignty was Ottokar’s Sceptre, a symbol of the independence and legitimacy of the current King, Muskar XII. This relic, depicting a pelican, which may have been inspired by Polish or Albanian iconography , is duly protected in the Royal Treasury room of Kropow Castle, located in Klow, the capital of Syldavia. This monument, the oldest and most important in the history of Syldavia, has a number of features that define it as Gothic.

From 1947 onwards, a new version of this narrative emerged, which, in addition to the colouring, brought some changes to the lines and decoration of the spaces, demonstrating the valuable contribution of Edgar P. Jacobs. One of Jacobs’ most significant changes was the addition of religious representations adorning the walls of the Royal Treasury room, where the image of Saint George defeating the dragon with his spear can be seen. The use of this legend is yet another example of the attempt to achieve medieval iconography, which is usually found in Gothic churches and convents. As for Kropow Castle, the changes are quite noticeable, converting the Late Gothic lines present in its main portal, dating from the 14th to 16th centuries, to the early Gothic style of the 12th century, as conveyed to us by Villard de Honnecourt’s Album from the mid-13th century. This change is in line with the history of Syldavia itself, which is reflected in the tourist brochure that Tintin reads on the flight to Klow. According to this informative document, the kingdom was founded in the mid-12th century, a time when Gothic architecture first appeared, with the Basilica of Saint-Denis in Paris as its inaugural monument.

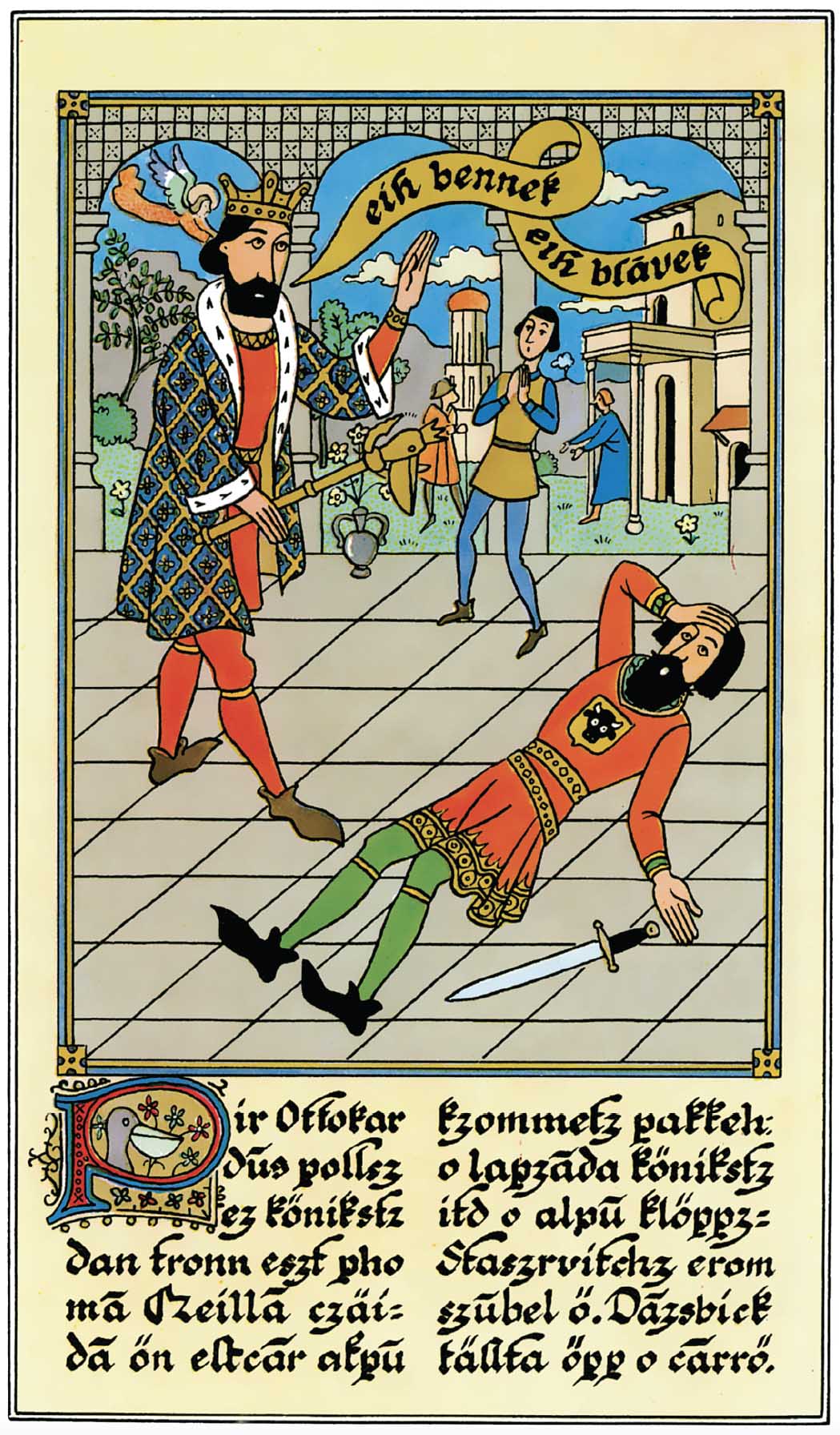

In 1360, Ottokar IV ascended the throne, from whom the legend of the Sceptre originates, giving rise to the ritual of passing this object between the legitimate kings of Syldavia. In addition, Ottokar IV unified the country, thus becoming a refounder of its independence. To make it even more believable, Hergé depicts an illumination illustrating the legend mentioned, which is said to come from the 14th-century manuscript The Memorable Deeds of Ottokar IV.

Therefore, Kropow Castle must have been built during the 14th century, a period when Gothic architecture was undergoing transformation and was already being applied on a larger scale in military and civil architecture, abandoning its theological significance. We shall begin this analysis with the different types of arches that we see in the castle’s gateways. The main portal, located in the wall, features a pointed arch, the closest example of early Gothic architecture. In contrast, the original 1939 version corresponded to a metamorphosis of Gothic architecture that began to emerge between the end of the 14th century and the end of the 15th century, where we can observe the use of heraldry engraved in stone and ogival shapes altered from their usual geometry. Late Gothic adopted these characteristics in monumental buildings in England, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and other European countries.

The coat of arms above the portal bears the royal arms of Syldavia, with the iconography of the pelican. This animal is represented on different national objects of this kingdom, such as Ottokar’s Sceptre, the medal of Knight of the Golden Pelican Order, the royal carriage and the national flag of Syldavia. In the Middle Ages, the pelican was engraved in churches as a biblical symbol. King D. João II of Portugal (1455-1495) had a pelican feeding its young with its own blood as his personal coat of arms. It was a Christian metaphor for mercy. In the Unfinished Chapels of the Batalha Monastery, this coat of arms is still preserved today, engraved in limestone at the top of half of its pointed arches.

Since the 19th century, some countries have succumbed to the temptation to name their national Gothic style. In Portugal, Francisco Varnhagen gave it the name Manueline, referring to King D. Manuel I. England preferred to call it Perpendicular, given its height. John Ruskin wrote about the foundations of Venetian Gothic in The Stones of Venice, a work that also contributed to these discoveries. We might even wonder which of these Gothic styles Hergé decided to apply to Kropow Castle. But as we study all the elements and variations of Gothic present in this album, we realise that the monument combines a mixture of styles, all derived from the most original Gothic. Given the uniforms of the Royal Treasury guards depicted in the original version, which are too similar to those of the British Royal Family, we can assume that Hergé was also inspired by English Gothic architecture. In fact, if we look at the 1939 version, the castle closely resembles the Tower of London, where the British Crown Jewels are also kept.

In the second portal, which provides access to the Castle, the forms are derived from 14th and 15th century Gothic architecture, examples of which include the main portal of the Batalha Monastery in Portugal, the main portal of Beverley Minster in England, and the arches preceding the altar of St. Peter’s Church in Leuven, Belgium. Here, there is an extension of the upper arch that ends in a finial, combined with a lower round arch, flanked by two columns with Corinthian capitals. By comparison, the arches found in the St. Peter’s Church in Leuven and the arch of the main portal of Antwerp Cathedral are almost identical to the forms created by Hergé. Interestingly, we know that the Belgian author later visited Antwerp, thanks to a photograph with Bob de Moor, dated 1957.

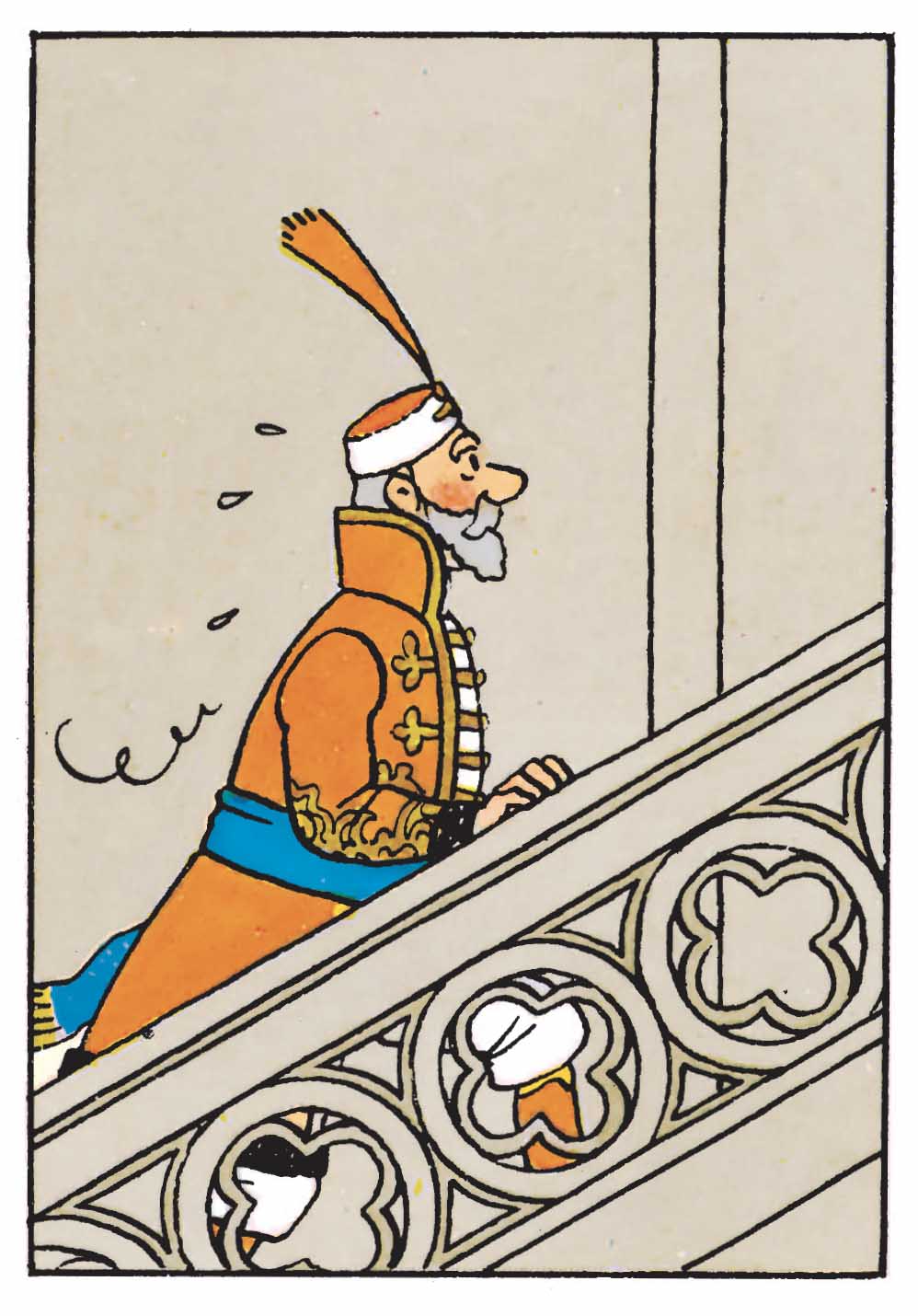

As for the limestone staircase, we can admire the decorative motifs in the shape of a fourleaf clover (quatrefoil), so characteristic of the Gothic architecture. This decorative element can be found in stained glass windows, bas-reliefs and limestone sculptures. For example, in Venice there are windows with this shape on the façade of the Palazzo Ducale, built by Giovanni and Bartolomeo Bon in the mid-15th century. On the flying buttresses of the Batalha Monastery, two four-leaf clovers carved in limestone can also be seen, which are echoed in the bas-reliefs next to the main portal, built between 1388 and 1438. Once again, the St. Peter’s Church in Leuven corresponds to this, its interior being decorated with a profusion of this decorative element in bas-reliefs. But the most likely source of inspiration must have been the staircase of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, which displays this quatrefoil in all its splendour.

Outside Kropow Castle, we can see a buttress, which is usually found in Gothic churches, with the purpose of supporting the central nave.

In this adventure, we witness the creation of a country whose origins date back to the Late Middle Ages. The Gothic style also serves to give historical weight to the narrative, since the first conflict between Syldavia and Borduria dates back to the year 1195. In the album The Calculus Affair, we revisit Borduria and catch a glimpse of the façade of Bahkine Fortress, with its pointed arch portal, alluding to this medieval past shared with Syldavia. To further highlight this historical context, in the book King Ottokar’s Sceptre, we are confronted with a page from a medieval manuscript, found in the archive room of Kropow Castle. In this small image, we notice the Gothic arches of a certain structure without context. We only need to see its contours to understand that it is an ancient book of great cultural value. In addition to the mystery, Gothic architecture plays an important role in the identity of the Middle Ages, which readers generally associate with this style.

If we analyse the Late Gothic style in the Bohemian region, we can see that inspiration must have come from its architectural solutions, the greatest examples of which are Prague Castle and St. Vitus Cathedral. These monuments underwent significant changes in the 14th century, ordered by Charles IV of Bohemia (1316-1378). Charles Bridge was also built during this period, designed by Peter Parler, one of the most renowned architects of the Bohemian Late Gothic period. Prague Castle is also a defensive bastion, where the Bohemian Crown Jewels are kept inside St. Vitus Cathedral.

In addition to architectural resemblance, historical and narrative similarities can also be detected. At the beginning of this Tintin adventure, we are introduced to the Royal Seal of Ottokar IV, which was discovered in Prague by the researcher Nestor Halambique. A few pages further on, we see Tintin leafing through an encyclopedia, where he reads that we should not confuse Duke and King Ottokar I of Bohemia with Ottokar I of Syldavia. In these small details, Hergé gives us a glimpse of his documentary sources. Charles IV of Bohemia is said to have ordered the creation of the Crown, Orb and Sceptre, which were originally kept in Karlstejn Castle, which in architectural terms is the closest to Kropow Castle as depicted in the final version of this album, both dating from the 14th century. Therefore, there is a great similarity between Charles IV and Ottokar IV, who gives his name to the title of the adventure and was also the first to wield the royal sceptre.

As we know, Hergé may have been influenced by the German annexation of Austria on 12 March 1938, with the first page of King Ottokar’s Sceptre being published on 4 August of the same year. The fact is that Prague was taken by Germany on 16 March 1939 and declared by Hitler as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. During this period, King Ottokar’s Sceptre was published weekly in the newspaper Le Petit Vingtième. These facts give us an idea of how Prague and the Bohemia region played a historical and artistic role in the creation of the Kingdom of Syldavia. Despite this, Hergé stated in a letter to editor Charles Lesne, dated 12 June 1939, that Syldavia was Albania, referring to its annexation, which was carried out by Italy in April of the same year.

The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rakham’s Treasure

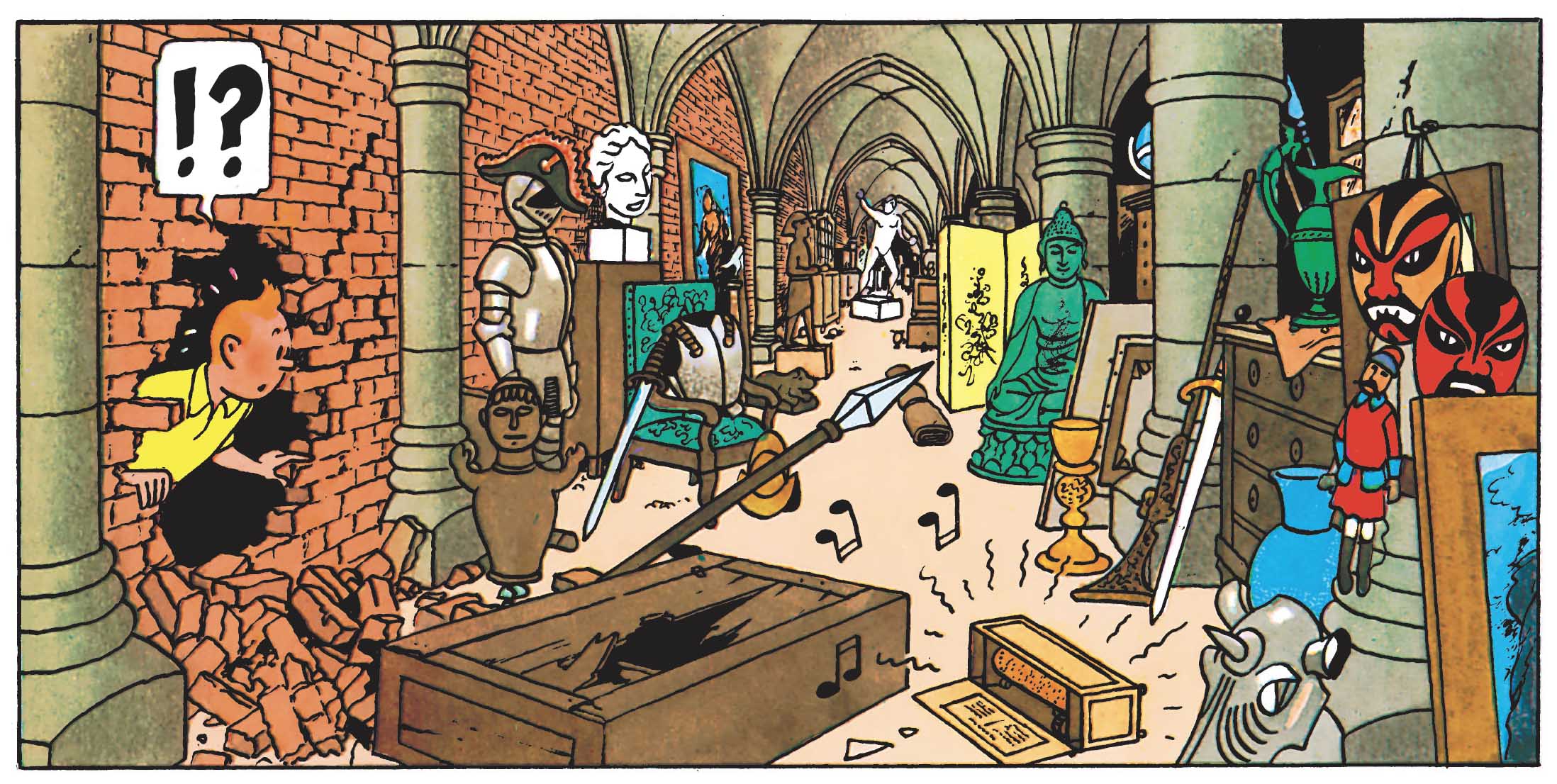

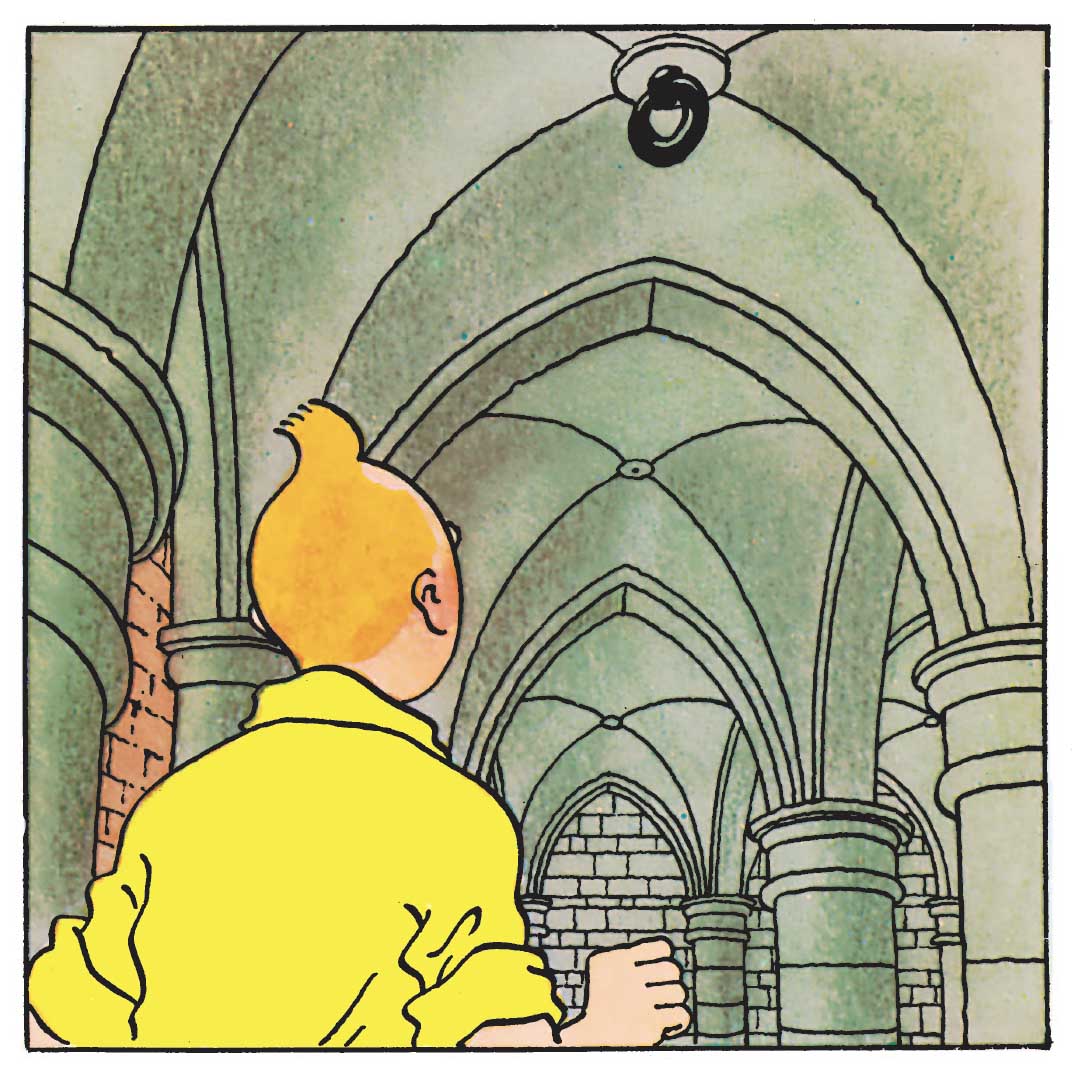

In the albums The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rakham’s Treasure, we are introduced to a new type of Gothic architecture, possibly an ancient crypt of a medieval church that has disappeared. This underground chamber, located beneath the foundations of the Marlinspike Hall, holds the key to all the secrets surrounding the discovery of the treasure that the navigator Sir Francis Haddock brought back from his travels. The crypt therefore represents the culmination of the two adventures.

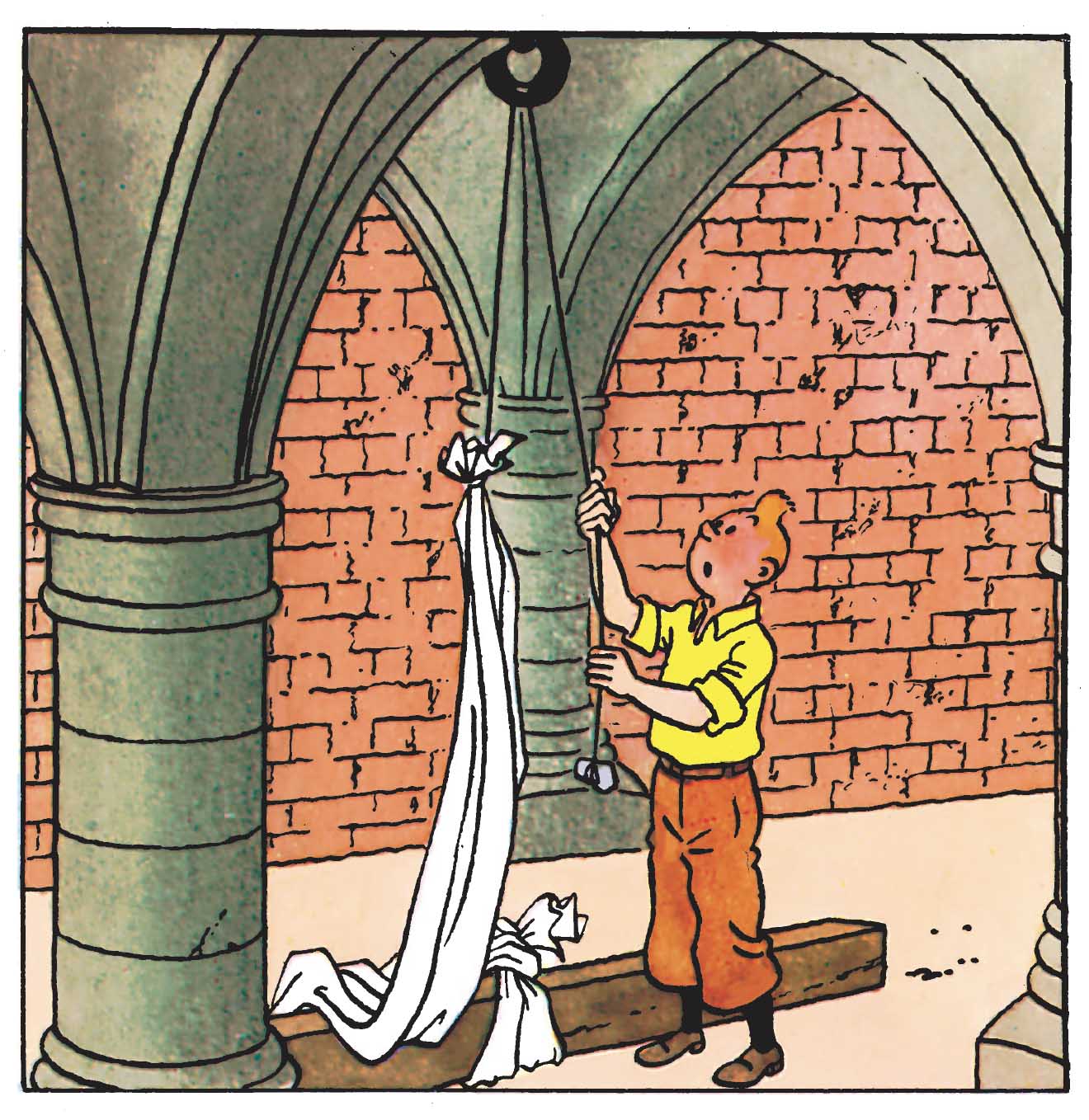

Its first appearance in The Secret of the Unicorn provides us with more details about the structure, featuring massive columns, commonly used in the central naves or crypts of Gothic churches, with the purpose of supporting the complex work of the pointed arches that sustain the ribbed vaults. In fact, the vaults are designed by Hergé in a more primitive Gothic style, supported by four arches. We even see the closure of the vault with an iron ring, allowing Tintin to suspend the wooden beam with a sheet in order to destroy one of the walls and escape from that improvised prison. Even this mechanism devised by the hero may have been inspired by the battering ram, a weapon from Classic Antiquity that was widely used in medieval sieges.

The underground complex as a whole corresponds to several medieval examples, such as the east crypt of Canterbury Cathedral, founded in the late 12th century. In the crypt of the Saint Hermes Basilica in Ronse, we also find the same columns and vaults, this example being one of the oldest and largest in Belgium.

Chillon Castle stands out as one of the most visited monuments in Switzerland, a country that Hergé knew well. The monument has been documented since the 10th century and its crypt later served as a prison, as Lord Byron tells us in his poem The Prisoner of Chillon, written in 1816. Given the Gothic architecture of the crypt, with its fortified columns and ribbed vaults, we believe it may have been restored during the 13th-century works carried out by the Savoy family. Lord Byron admirably describes the space in his poem: ‘There are seven pillars of Gothic mould, / In Chillon's dungeons deep and old, / There are seven columns, massy and grey,…’ Lord Byron refers to the imprisonment of François Bonivard in the 16th century, while Hergé recounts the imprisonment of Tintin in the 20th century.

Cheverny Castle, in the Loire Valley, was Hergé’s main inspiration for creating Marlinspike Hall. The details of its exterior, excluding the side towers, were reproduced in minute detail. Inside, we can see the exact replica of the staircase, the 16th-century armour, among other features. The tourist brochure for Cheverny Castle that Hergé had in his possession attests to this inspiration, even though Cheverny does not have a Gothic crypt. The Castle was only built between 1624 and 1630, while Marlinspike Hall does not have an exact date of construction, having been donated by King Louis XIV of France to the knight Sir Francis Haddock in 1684.

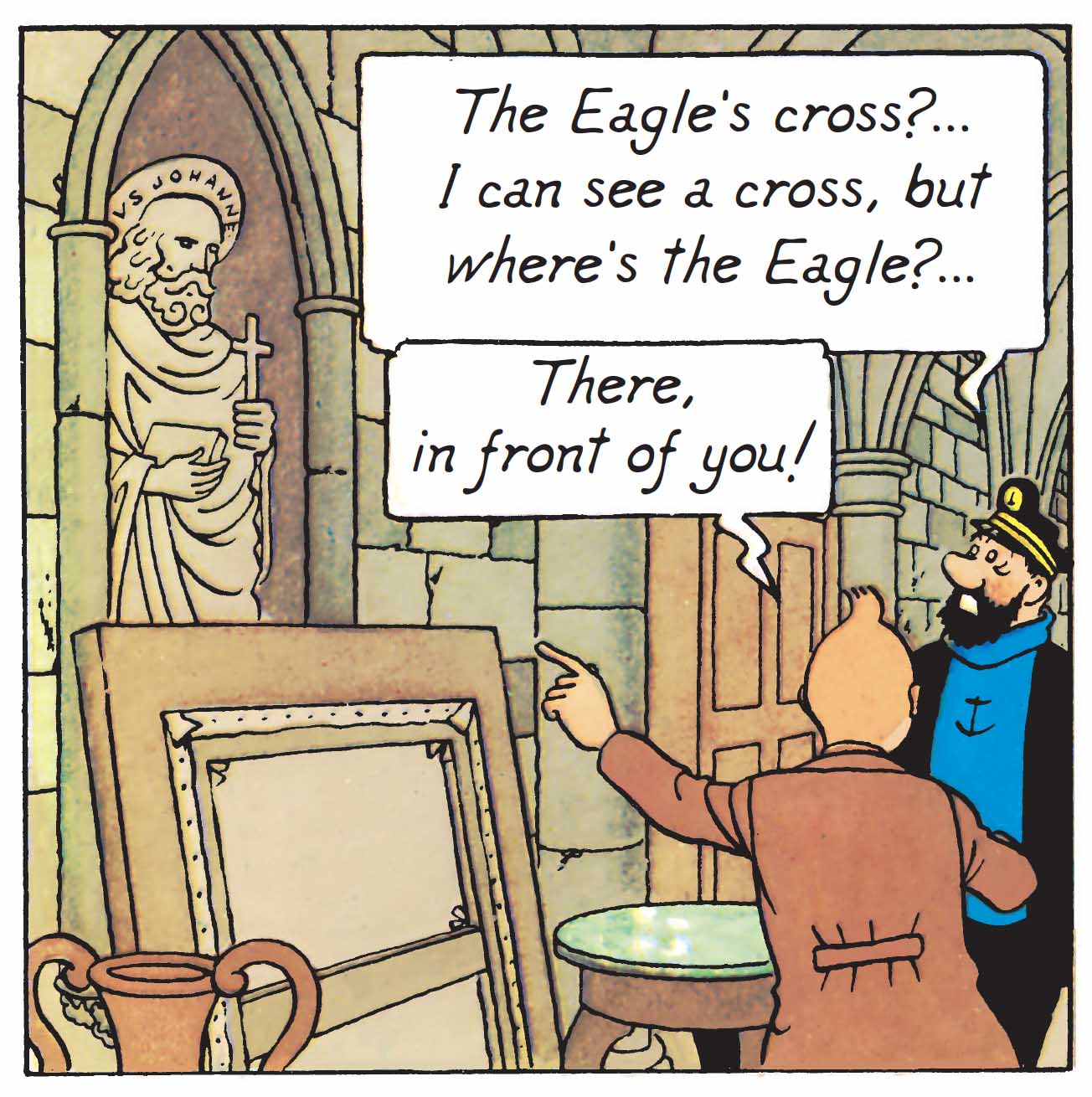

Therefore, Hergé does not give us an answer about the earliest date of Marlinspike Hall’s existence. It is most likely a castle that has undergone several architectural interventions since the Middle Ages. The crypt hides many artefacts spanning centuries of History, but there is one that deserves our attention. The statue of St John the Evangelist is carved on a corbel and integrated into a niche with an ogival arch. St John the Evangelist accompanied by his eagle is one of the indispensable images in any Gothic church. Perhaps for this reason, Tintin said, after finding the sculpture of St. John the Evangelist: ‘... We must be in an old chapel...’ Therefore, this crypt may be a chapel forgotten by time, which now supports a 17th-century castle.

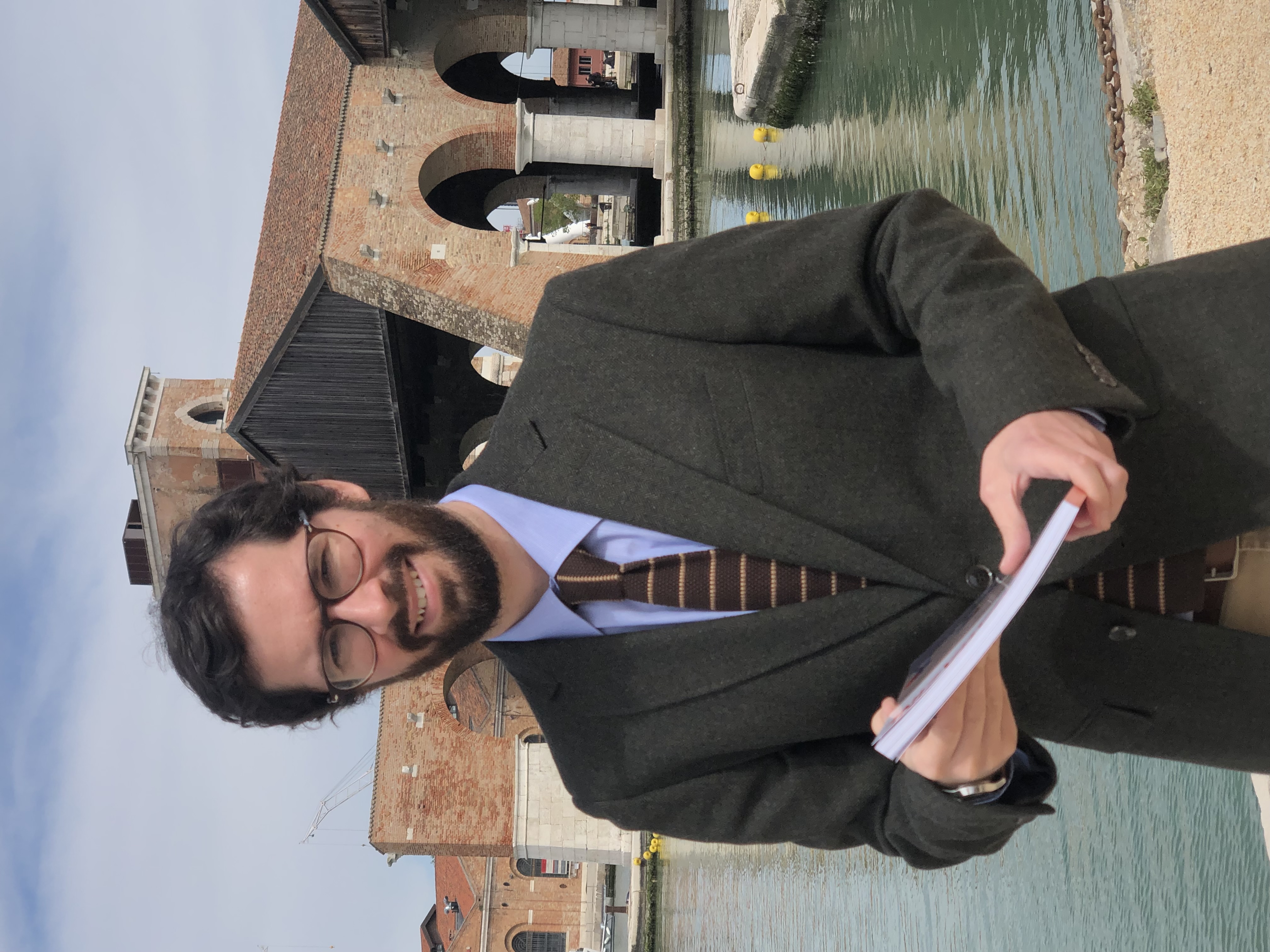

About the author

Francisco Teles da Gama holds a Bachelor in History, a Master's in Medieval History and is a Doctoral Researcher in Art History at the School of Arts and Humanities of the University of Lisbon, with a grant from the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I. P. He is a researcher at ARTIS - Art History Institute at the School of Arts and Humanities of the University of Lisbon. Francisco has carried out archive and research work in various museums and monuments, such as the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, the Batalha Monastery, the Bordalo Pinheiro Museum and the Museum of Lisbon, among others. He was a member of the committee for Leiria's bid to become European Capital of Culture 2027. He has been the scientific coordinator of conferences dedicated to historical and artistic heritage. Francisco is the founder and director of FITA - Friends In The Arts and editor of the international arts and culture publication FITA Magazine, honored with the High Patronage of the President of the Portuguese Republic. The volume FITA Magazine - Floating Waters represented the Portugal Pavilion at Expo 2025 Osaka. He co-ordinated the International FITA Awards of Literature, which resulted in the book Portrait of the Artist as a Writer (FITA - Friends In The Arts, 2022). His artwork The Banquet of Eternity was exhibited at the Croatian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2024. He published the novel Cantiga para Poeta em Águas-Furtadas (Song for Poet in Attic, Book Cover Editora, 2024).

Pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025. Except portrait of Francisco Teles da Gama © Francisca Gigante 2024

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books