The Secrets of Hergé Studios: Behind the Scenes of Tintin

When we look back at Tintin’s early days, everything seems so simple. A fearless young reporter, adventures across the globe, and instant success. Since 1929, Hergé had produced album after album, winning over millions of readers. Yet, in the aftermath of the war, the creator of Tintin found himself in doubt. Fatigue caught up with him, inspiration ran dry, and he sensed that something had to change.

As the 1950s began, Hergé entered a pivotal period. Following the triumphs of his earlier works, he now faced a double challenge: to move beyond familiar formulas and to invent a creative process capable of launching his hero to the stars — long before Professor Calculus’s rocket ever took flight. In this context, he reorganized his working environment and laid the foundations for what would become a true ‘dream factory’: the Hergé Studios. Tintin’s restless energy was just getting started.

This transformation marked a shift from artisanal craftsmanship to a fully-fledged collective operation, bringing together researchers, writers, artists, colorists, scientists… all working under the demanding eye of Hergé, a conductor in constant pursuit of precision and realism.

At the turn of the 1950s, Hergé effectively entered a pivotal period.

It was in this singular crucible, where discipline met imagination and tension met brilliance, that the Tintin of the 1950s took shape: a modern hero, ready to reach the Moon and secure his place in the history of comics. Everything was set — pencils warming up, minds buzzing.

So let’s open the door to the studio together!

The Birth of the Hergé Studios

If you could slip into the margins of the comic panels, just beside Hergé’s line, you might catch a turning point in the making. The late 1940s were no easy time for Hergé. The aftermath of the war had left its mark: personal tensions, creative doubts, nervous exhaustion. Yet, rather than sink under the weight of it all, he chose to reinvent himself. As long as there was an idea to explore and a line to draw, nothing was lost.

The opening of the Hergé Studios at 194 Avenue Louise in Brussels marked a decisive shift. From that moment on, it was no longer simply a matter of “making albums,” but of rethinking the entire creative process. Documentation, drawing, color, dialogue: everything was studied, checked, refined. The worktables overflowed with stacks of photos, models, and sketches. Each page passed through many hands, revised and reworked during long meetings where ideas sparked and clashed.

Gradually, Hergé imposed a real method. The Studios functioned like a small publishing house unto themselves. Work sessions were punctuated by réunions d’arpentage — surveying meetings — in which every panel, every line of dialogue, every backdrop was dissected. Everything was debated, everything defended, but in the end, Hergé always had the final say. Nothing left the studio without his approval. Nothing was left to chance. In Explorers on the Moon, published in 1954, French astrophysicist Roland Lehoucq later confirmed: “[...] there are many things that are very coherent, very reasonable, and actually very, very well done.” (Radio France, interview available in French only). It’s impossible not to dive back again and again into these pages, so rich in detail.

The Essential Collaborators

One could almost picture Hergé as Captain Haddock standing before Marlinspike Hall — aware he has found his safe harbor, yet fully conscious that he now needs a crew to carry the adventure forward. To guide this transformation, Hergé surrounded himself with a team of complementary talents.

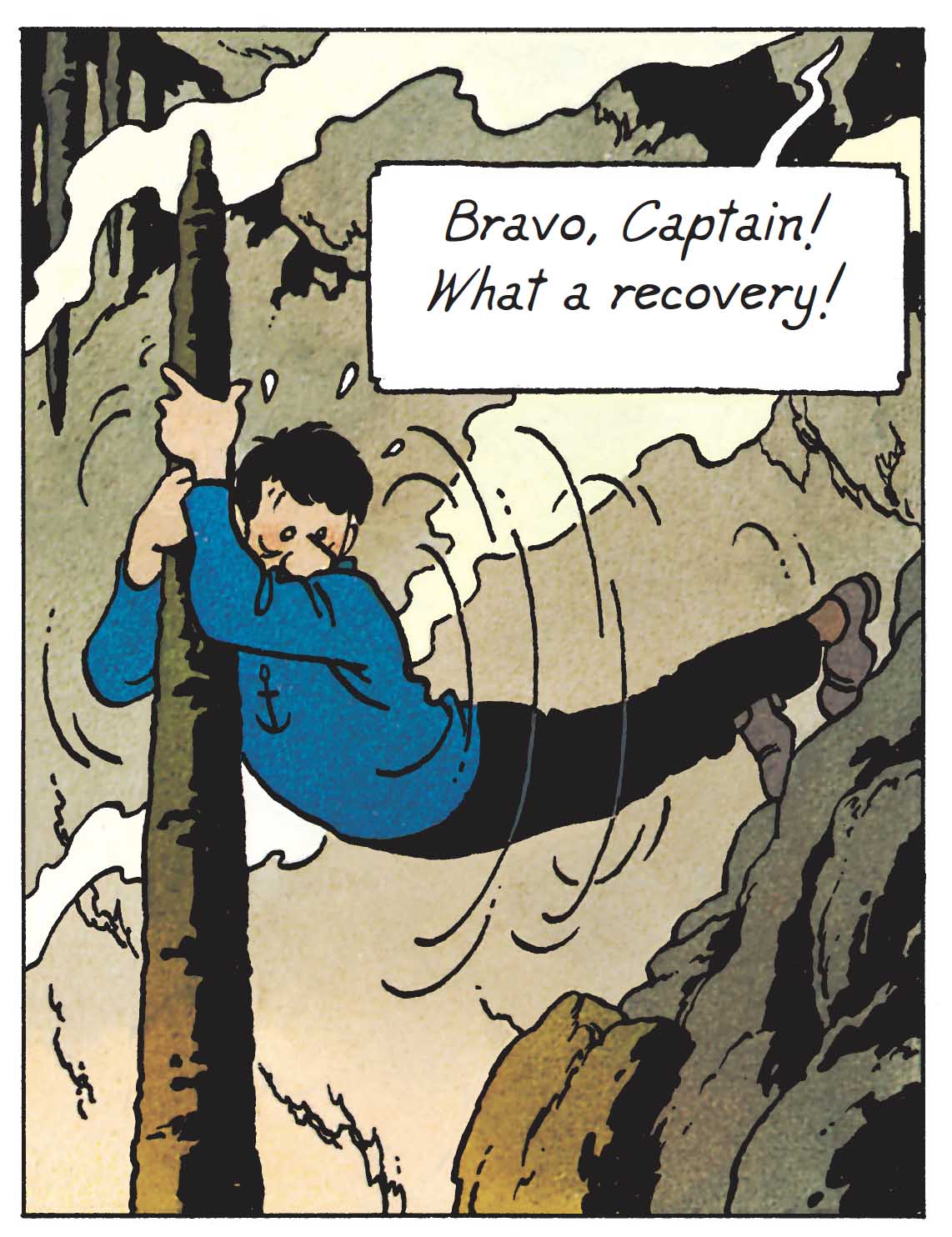

Bob De Moor, who joined in 1951, quickly became Hergé’s right-hand man in all things graphical. A virtuoso draftsman, he undertook meticulous field research: photographing locations, studying light, and noting architectural details. For Destination Moon, he even visited scientific facilities to understand spatial volumes and proportions. His sketches directly enhanced the visual precision of the albums, down to the shadow of a building or the texture of a metallic surface.

Jacques Martin, passionate about history, technology, and architecture, brought invaluable expertise. Vehicles, military uniforms, machinery — nothing escaped his eye. He provided detailed diagrams, annotated plans, and his obsession with accuracy grounded Tintin in a coherent, believable world.

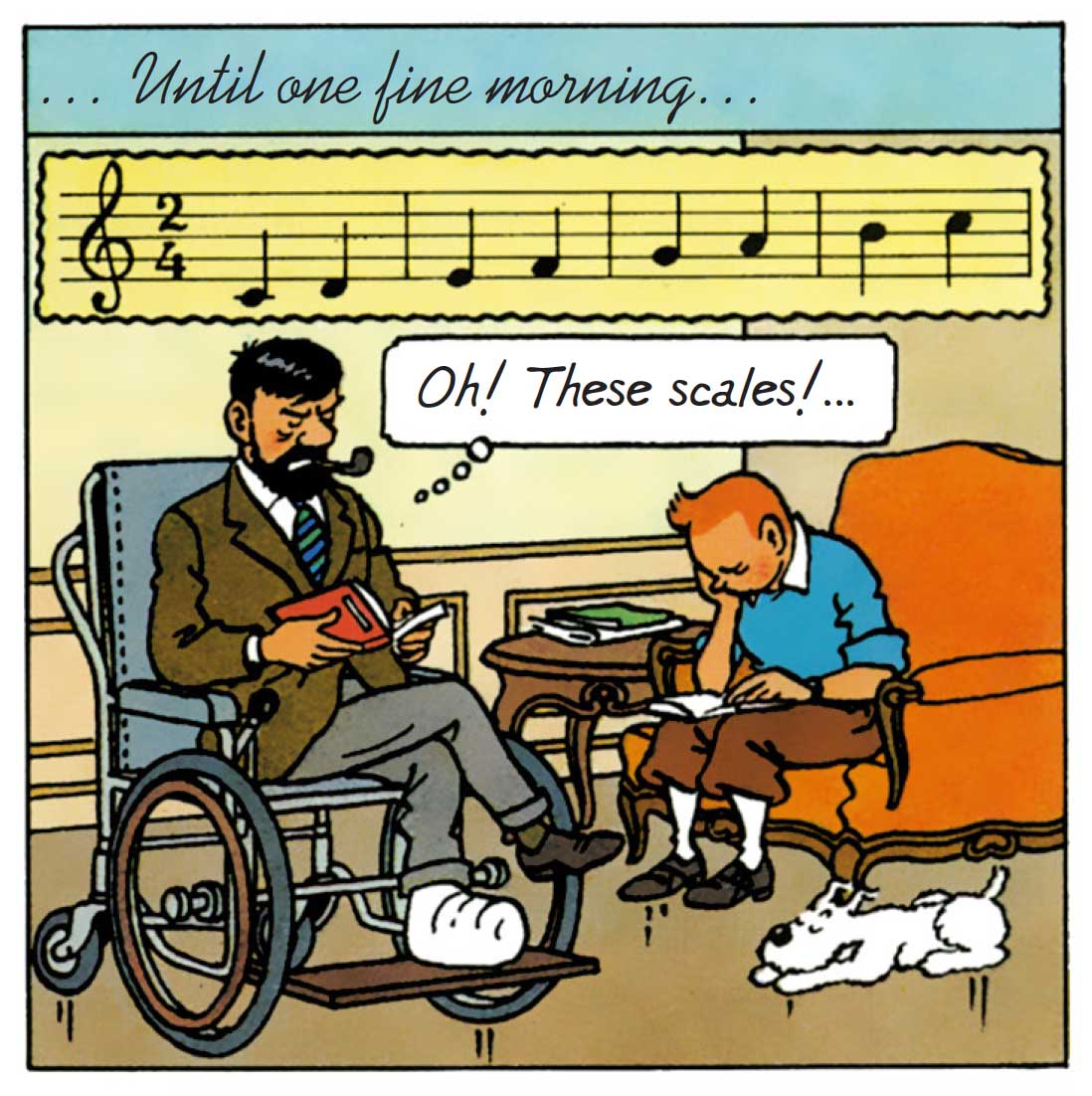

Roger Leloup, who began working with Jacques Martin in the early 1950s, officially joined the Studios Hergé in 1955. He specialized in technical backgrounds and vehicles, drawing mechanical elements with remarkable precision. His work includes the Geneva train station in The Calculus Affair, Haddock’s wheelchair in The Castafiore Emerald, and the Carreidas jet in Flight 714 to Sydney. His attention to technical detail was perfectly aligned with the Studios' documentary standards.

Josette Baujot, chief colorist from 1954 to 1979, developed a true science of color. Each tone was codified, sample boards were meticulously documented, and everything was checked to ensure perfect chromatic consistency across albums. She was one of the few able to stand up to Hergé, who nevertheless placed his full trust in her.

Albert Weinberg, discreet yet invaluable, contributed occasional dialogue ideas, scenes, or visual gags. Some of his suggestions were used as-is, others were reworked to better fit Hergé’s style. He also contributed to the research phase on space and aviation for Destination Moon.

Finally, Baudouin van den Branden, Hergé’s personal secretary from 1953 to 1974, oversaw the smooth running of day-to-day operations. He handled correspondence, reviewed dialogue with Hergé, and coordinated editorial requirements with both Casterman and the Tintin magazine.

Everyone contributed, but all knew that the 'Hergé style' remained the compass. Tintin’s voice stayed true.

The Pursuit of Absolute Detail

Step into the studio, the tables overflow with photographs, models, and sketches. In just a few seconds, it’s clear: nothing here is left to chance. Interiors, costumes, settings — everything is treated like a meticulously orchestrated stage production. Every object must have its own logic, its own story, even if it appears only once.

Bob De Moor brings back hundreds of reference photographs, Arthur Vanoveyen constructs a 1:33 scale model of the lunar rocket, and Alexandre Ananoff, an expert in astronautics, verifies every technical detail. Bernard Heuvelmans contributes pages upon pages of notes on gravity, weightlessness, propulsion systems, and the internal layout of the rocket. Some of his suggestions are included word for word — such as the famous gag of Haddock’s whisky floating in bubbles, or the Thom(p)son twins’ overly heavy boots.

This documentary precision goes far beyond the major scenes. Even a wall poster, an armchair model, or the placement of a door handle undergoes multiple rounds of verification. This constant attention to realism gives the albums a unique visual depth and reinforces the sense of authenticity that defines Tintin.

And yet, this realism never stifles imagination. The gags often arise from scientific constraints themselves. In Explorers on the Moon, for instance, the comic moments stem directly from Heuvelmans’ research. Hergé manages to blend accuracy and invention with a rare sense of balance.

The Backstage of a Collective Adventure

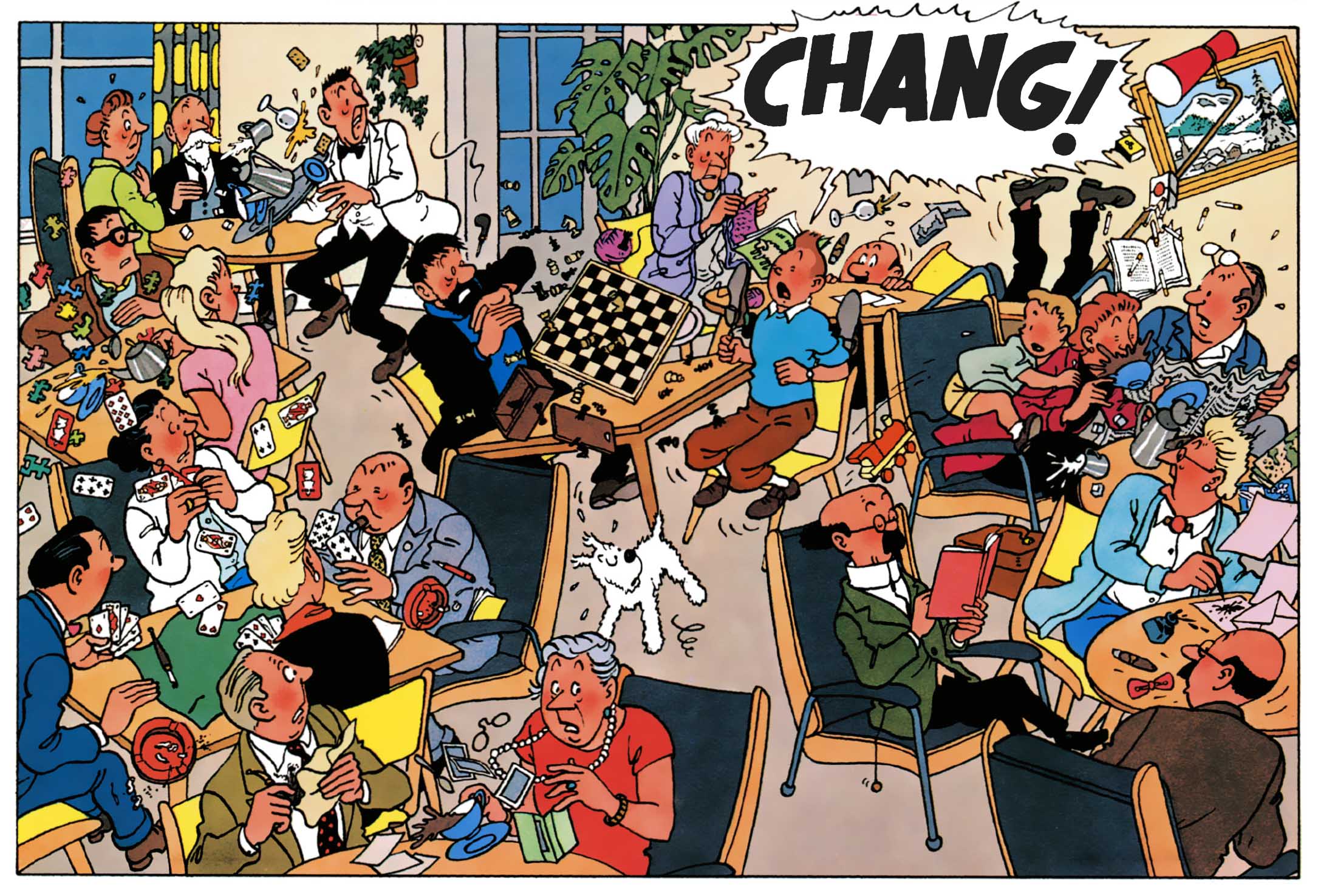

Behind the scenes, exchanges could be passionate: ideas, suggestions, and objections clashed during the meetings. Van Melkebeke would propose entire dialogue scenes, Jacques Martin defended his technical details, and Albert Weinberg dreamed up gags. Hergé welcomed all these ideas… but nothing was approved without being reshaped, simplified, or rewritten. He would read, annotate, sort, and ultimately decide alone.

Hergé as General Tapioca? Not quite... He was no dictator, but his standards were exacting. In the studio, he listened, consulted, considered every suggestion… yet the final call was always his. His overarching vision allowed him to weave together the contributions of others, reshaping them so they aligned with his distinctive style.

The daily atmosphere swayed between creative excitement and quiet tension. Sessions could stretch for hours. Gags were tested out loud, a single panel might go through three different versions, a word, an object, a shadow could be endlessly reworked. Josette Baujot sorted her color palettes onto cardboard boards, with every shade meticulously referenced to ensure consistency from one album to the next. Sometimes, Bob De Moor would return from field research, arms full of photos and sketches — and everyone would crowd around, searching for just the right light, the perfect angle.

Externally, editorial pressure was palpable. Casterman regularly intervened in Hergé’s work, demanding the use of color, enforcing narrative changes for reasons of marketability or sensitivity, and ensuring the profitability and acceptability of the albums. But Hergé refused to compromise. He would rather delay publication than sacrifice quality. These ongoing tensions help explain why the albums from this era reached an unprecedented level of artistic rigor in European comics.

A Turning Point for Tintin

The structuring of the Studios and the rise of a collective creative method profoundly transformed the very nature of Tintin. The character gained in complexity, the storylines deepened, and the albums reached a level of artistic rigor previously unseen in the history of European comics.

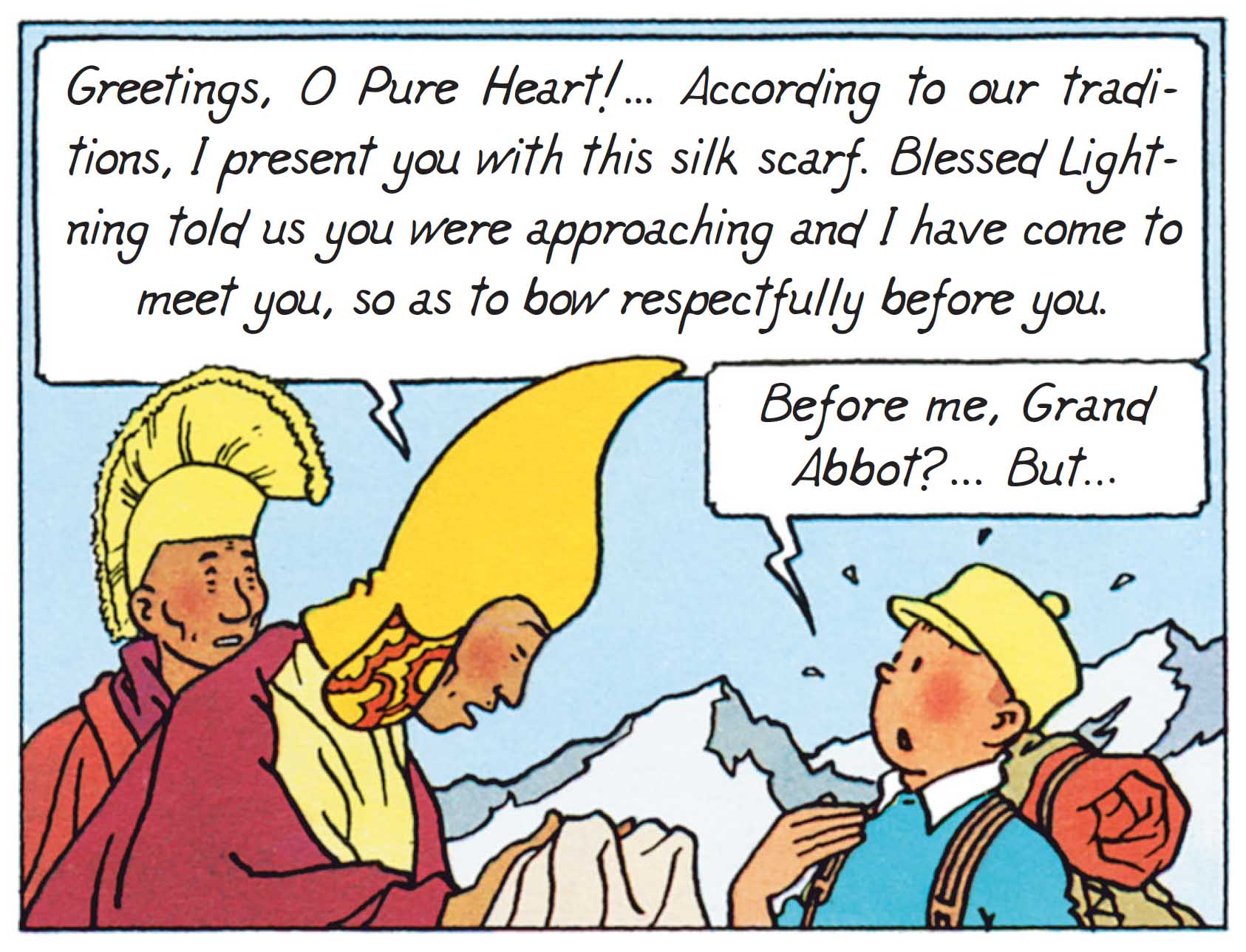

This period gave birth to a modern Tintin: more scientific, more grounded in reality, yet still humorous and accessible. The series entered a new dimension, paving the way for its greatest masterpieces.

The 1950s marked Hergé’s true “return to school”: a moment when he reshaped his creative process to bring forth a unique collective body of work. The Hergé Studios became the beating heart of a method built on documentation, precision, and collaboration.

In this buzzing workshop, Tintin ceased to be the creation of a single man and became the product of a collective intelligence, guided by a visionary perfectionist. And so, page by page, the legend of a myth was born.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books