When Hergé’s Penguins Lost the North

In the world of Jo, Zette and Jocko, geographical accuracy did not always withstand the pull of artistic imagination.

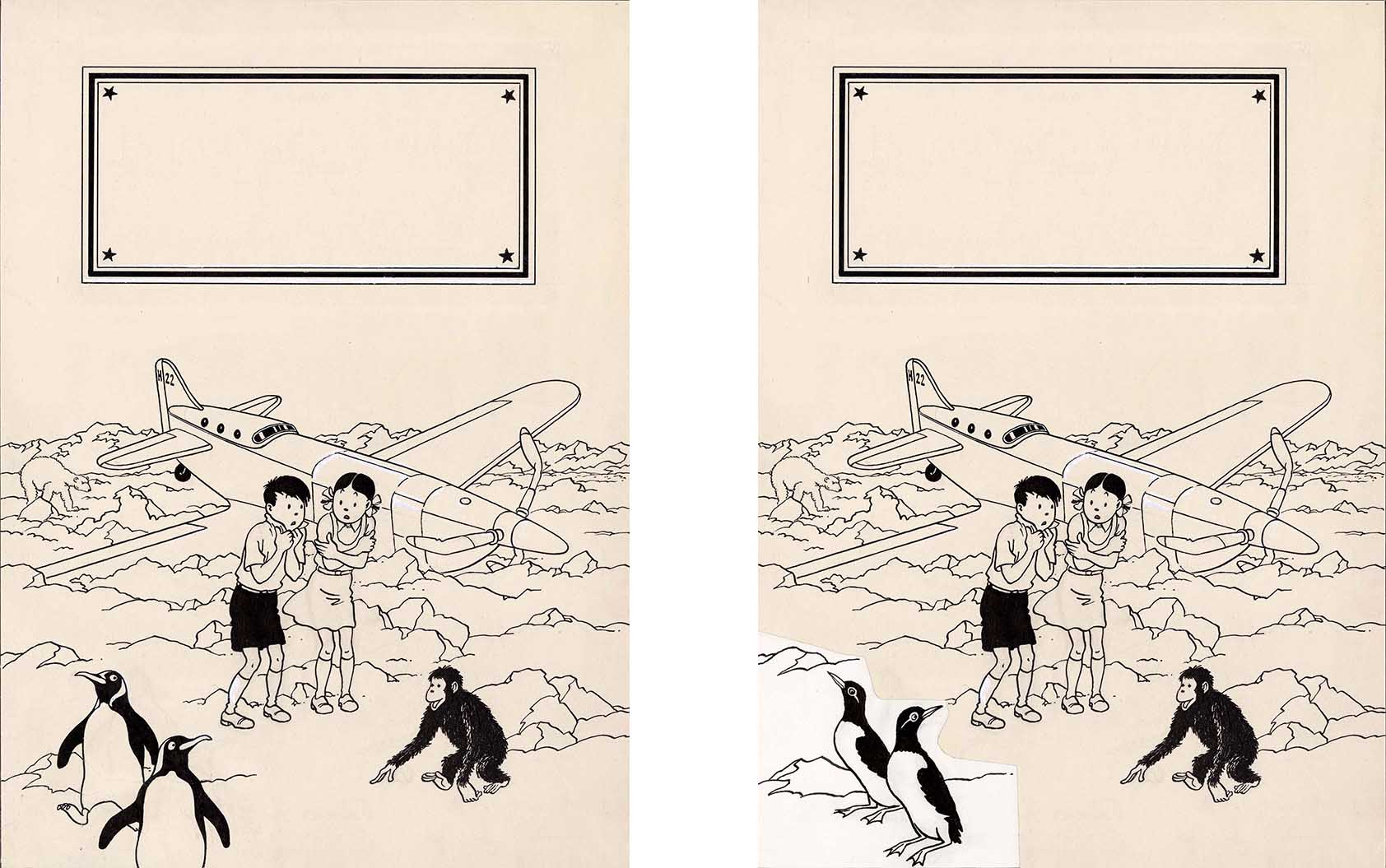

Nothing too serious, of course, but a small visual detail failed to escape the sharp eyes of zoological purists. In the first edition of Destination New York, the second part of The Stratonef H.22, Hergé sends his young heroes flying over the icy expanses of the Far North. On the ice floes, black-and-white birds dot the landscape… “penguins,” or so one believes.

An Icy Error

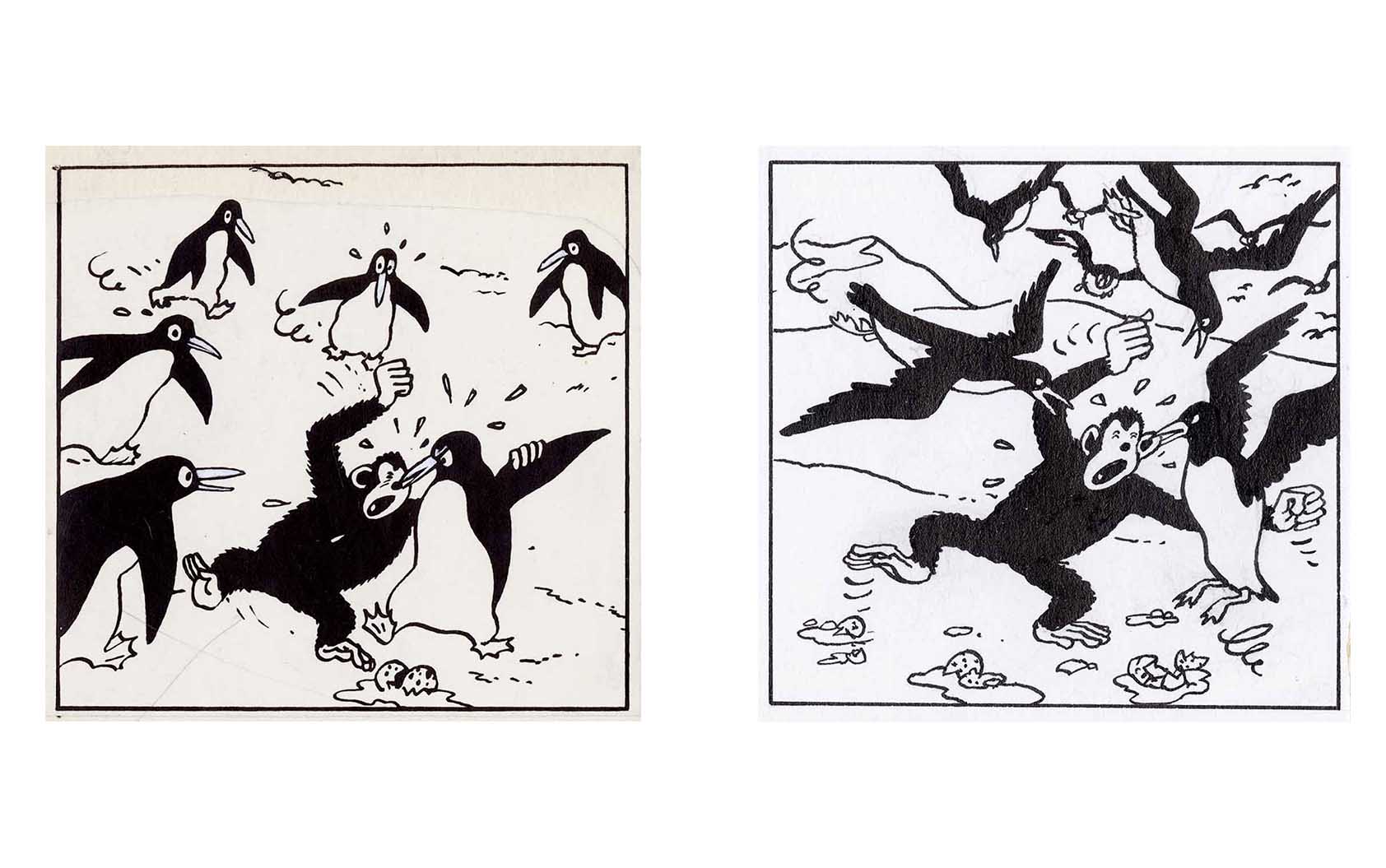

Only, these charming creatures, as Hergé had drawn them, standing upright on the ice, white-bellied, black-backed, wings pressed to their sides like little penguins of the South… could never have been found there.

Penguins, unable to fly, live exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere, around Antarctica. In the North, in Greenland for instance, one encounters other black-and-white seabirds: guillemots, murres, or - long ago - the great auk (Pinguinus impennis), now extinct.

In truth, Hergé’s lapse was less biological than geographical: his “penguins” could never have appeared on the ice of Greenland.

No wonder things get confusing, between penguins, auks, and guillemots, one might easily lose the North!

The Danish Observation

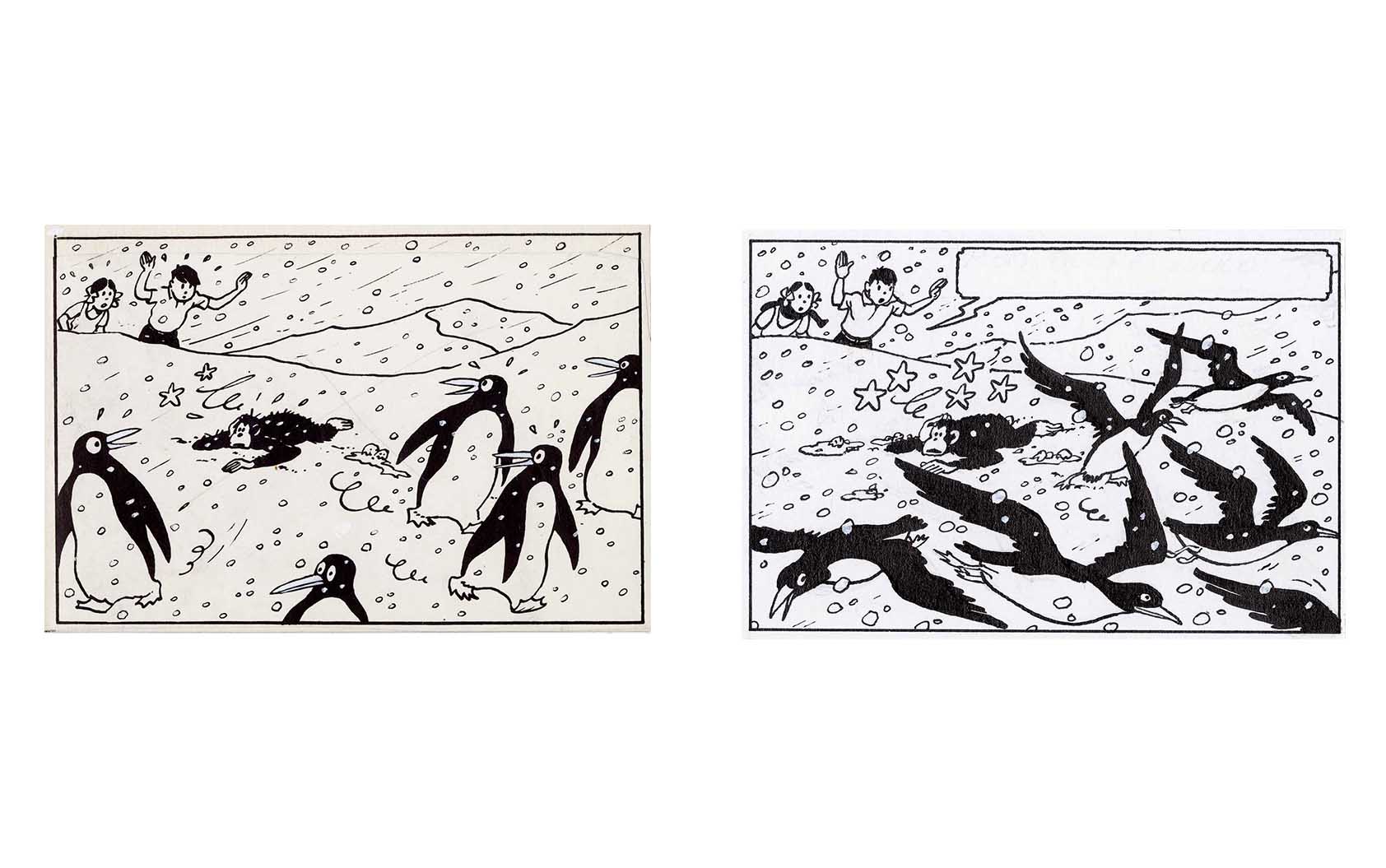

It was only several years later that a sharp eye spotted the inconsistency. In 1971, Danish publisher Per Carlsen pointed out to Casterman a zoological error in Destination New York. In a letter, he even suggested replacing « the penguins with muskox », animals far better suited to Greenland’s climate.

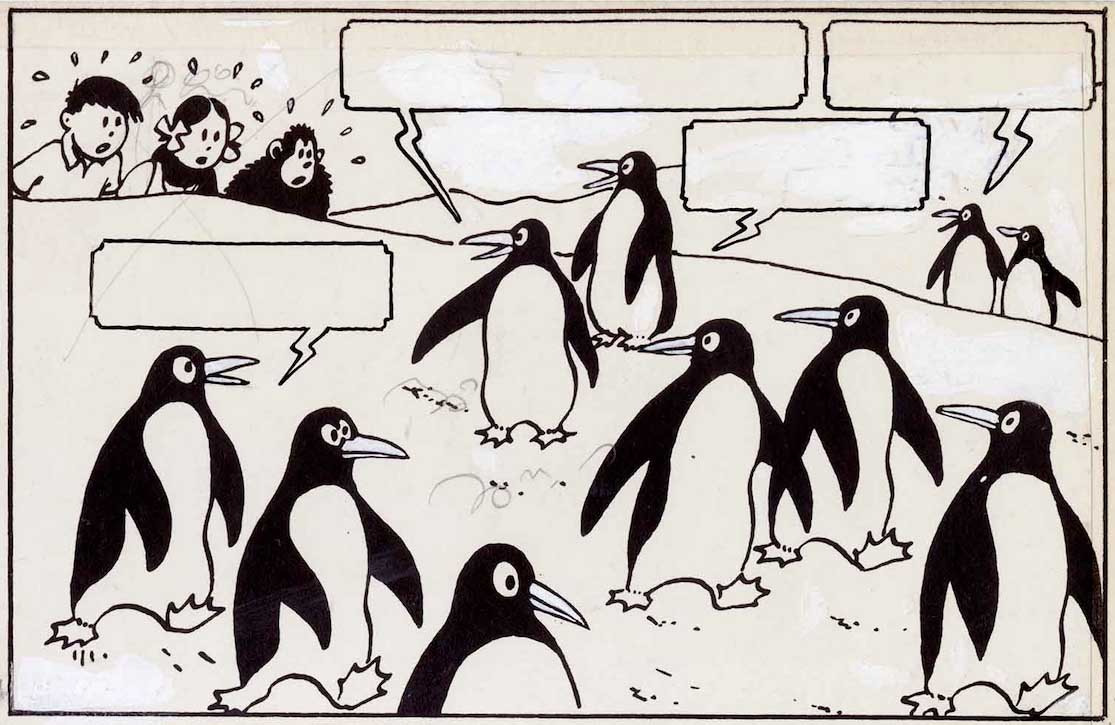

When Hergé returned from his travels, he took the remark seriously, but proposed instead to replace the penguins with guillemots or shearwaters, graceful northern seabirds. Carlsen promptly objected that « there are no birds in Greenland. » To avoid a full-blown ornithological debate, Casterman settled the matter pragmatically: the caption would be changed, replacing « Greenland » with « the Great North. »

Several panels were thus retouched: the black-and-white birds lost their penguin-like shape and came to resemble guillemots, true inhabitants of the Arctic.

Zoological purists may rest easy… Scandinavian editors do not trifle with precision, especially when the ancestors of the Vikings are involved!

The Precision Revisions

Though intuitive by nature and attentive to detail, Hergé did not always have access to rigorous documentation. After the freer spirit of his early years, he began striving to avoid anachronisms and contextual errors.

The « penguin affair » fits neatly into this quest for accuracy. It was no longer merely a question of aesthetics, but of credibility.

His quiffed hero roamed the globe, and every setting, every uniform, every animal now had to look right. Even in a lighter, less realistic series than Tintin, Hergé wanted every detail to ring true.

A Small Lesson in Rigor

Beyond the anecdote, this « battle of the penguins » reveals much about Hergé’s relationship with truth and realism.

His albums, long considered children’s adventures, were also the playground of an almost scientific perfectionism. Whether it was the design of an aircraft, the cut of a uniform, or the wildlife of the polar regions, nothing was too trivial to escape scrutiny.

Carlsen’s letter, incidentally, did not deal only with fauna. In the same correspondence, the Danish publisher also suggested replacing Father Francœur, a religious figure in the series, with a lay character. It was a recommendation very much in keeping with the Scandinavian spirit of the time, when religious neutrality was becoming standard in children’s publishing.

But this story also serves as a symbol: if even the greatest authors can make mistakes, only the best correct them. Hergé was undoubtedly among the latter. If you’re the skeptical type, just leaf through the albums of Tintin, and now perhaps of Jo, Zette and Jocko. Who knows? You might be the next guardian of lost details… or stumble upon a runaway penguin on the ice!

Textes et images © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books