Tintin and the Mail: An Explosive Affair!

And while, at this festive time of year, receiving news (good news at least) is a source of joy for most people, for our hero things are a little more complicated.

Letters, telegrams, press clippings, hastily scribbled notes… Tintin spends a good part of his time stopping to read, and these moments of apparent stillness often propel him toward a new challenge, very often at the other end of the world.

This is no coincidence. In Hergé’s work, adventure never appears out of nowhere. It almost always begins with information being passed on – often incomplete, sometimes misleading, rarely definitive. Before running, Tintin opens an envelope, with Captain Haddock, perplexed or furious, never far away. Before rushing headlong into danger, he unfolds a crumpled piece of paper. And often, what he reads more problems than it solves. So it is this role, both modest and decisive, of letters, telegrams and other papers that we invite you to explore this month.

The message that launches the adventure

Whether it is a mysterious envelope slipped under his doorstep or a casually dropped note, such messages arrive at just the right moment to stir his curiosity (and ours), and are often enough to set an adventure in motion. These are precisely the kinds of messages which, discreet as they may seem, trigger the action.

In Tintin, messages have a very personal sense of urgency. They rarely arrive at the right time. Sometimes they precede events. Sometimes they shed light on them far too late.

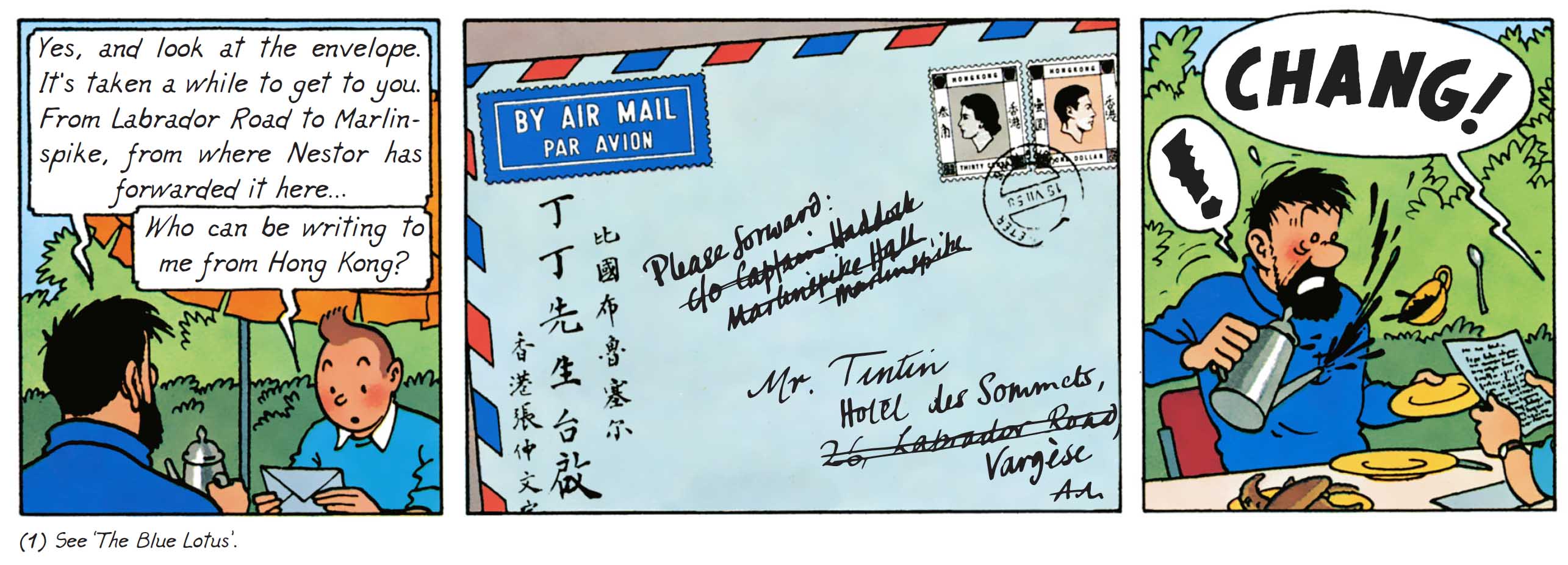

In Tintin in Tibet, everything begins with a brief newspaper item reporting an air disaster in Nepal. Tintin, absorbed in a game of chess with Haddock, dozes off and has a dream. He sees Tchang buried under the snow, calling for help. At this point, nothing is based on official information. It is a vague unease, without tangible proof.

The following morning, a letter arrives from Hong Kong. It is signed by Tchang himself. He announces that he is well and preparing to travel to Europe, specifying his itinerary. Reading the letter, Tintin realises that Tchang was in fact aboard the very plane that disappeared. Far from being reassuring, the message makes the disappearance impossible to ignore. Tchang is in serious trouble, and not just a little – as the reader will soon discover; and for Tintin, no further explanation is needed: it is already time to go!

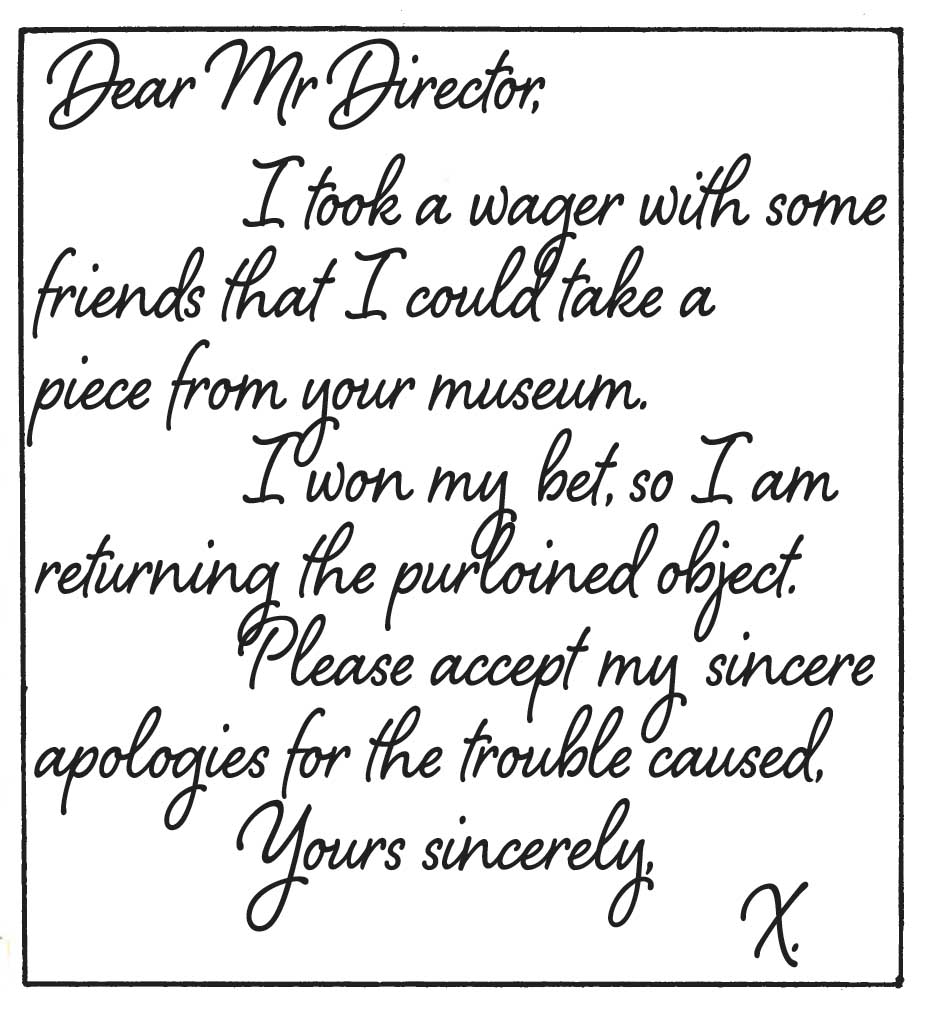

The same mechanism is at work in The Broken Ear. A strange message is left after the theft of the fetish, almost like a signature, meant to show everyone, and Tintin in particular, that a new plot is about to erupt and plunge him straight into the action. Later, an official letter from the police invites Tintin to attend the interrogation of two suspects. The machine is set in motion and sweeps us away to a fictional South American country.

Here, Hergé draws inspiration from the Gran Chaco War, which opposed Bolivia and Paraguay between 1932 and 1935. Renamed the « Gran Chapo », the conflict is transposed into the album through two barely disguised fictional countries: San Theodoros, echoing Bolivia, and Nuevo Rico, a double of Paraguay. Bang! from a letter to the green hell, there is only one step!

When the message becomes a mystery

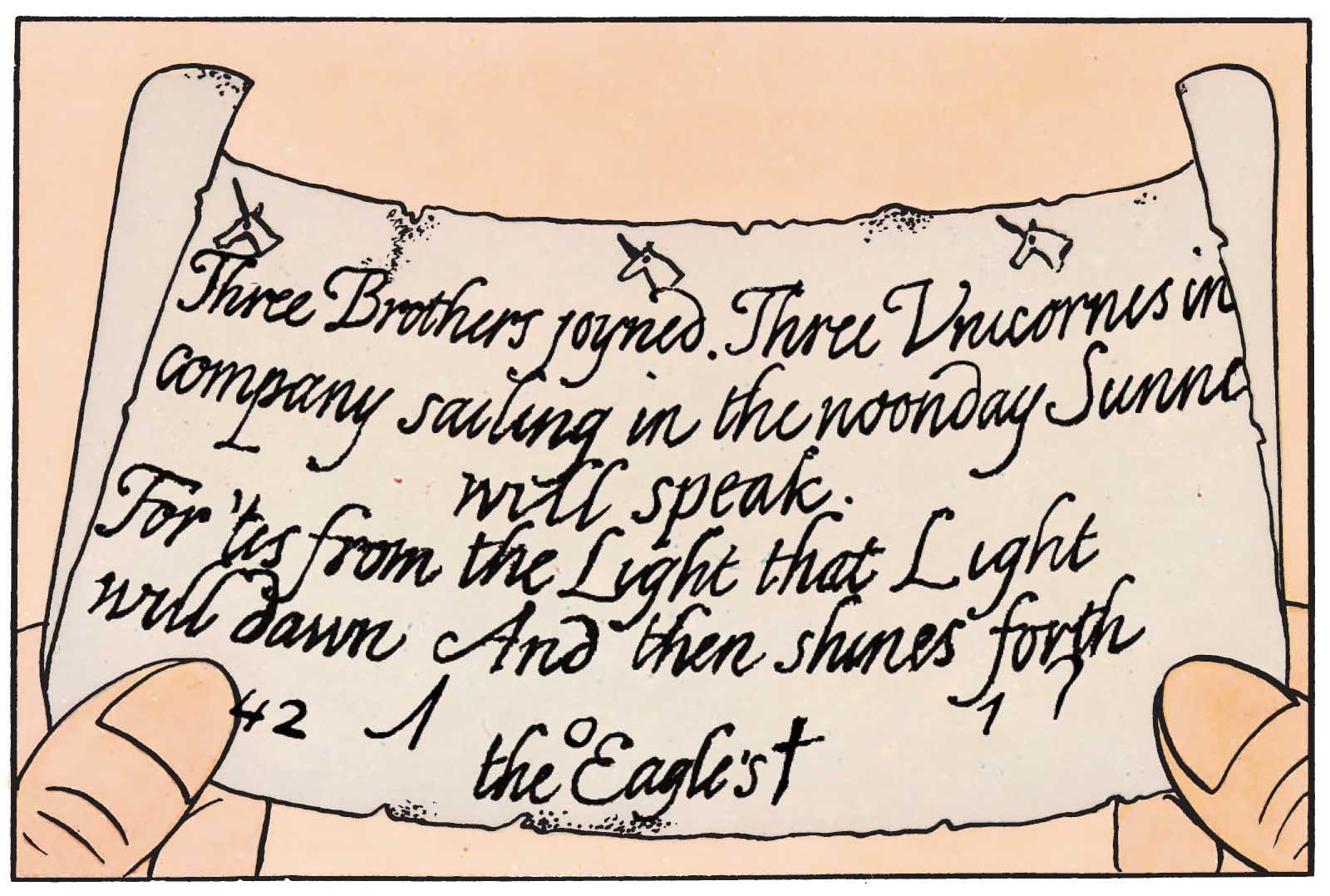

In The Secret of the Unicorn, the title sets the tone, and the course is set: the mysteries are thicker than the Bermuda Triangle. The adventure begins neither with a spectacular theft nor with a dramatic revelation (Hergé clearly enjoys surprising us), but with a perfectly ordinary purchase. Not just any purchase, though. Tintin buys a model ship at a flea market. Hardly has the transaction been completed when one, then two collectors become strangely insistent on buying it back. One of them is called Ivan Sakharine. Tintin refuses outright.

Soon afterwards, the model disappears. Tintin naturally suspects Sakharine, before recovering the ship and discovering, almost by chance, what truly makes it valuable. Examining the mast, he uncovers a small parchment carefully rolled inside. The text is incomprehensible, a string of words with no apparent logic. Tintin speaks of a « new mystery ».

The paper provides no immediate answers. It points to neither a place nor a clear objective. It poses an enigma with no instructions. Intrigued by this story of the ship, Captain Haddock rummages through his trinklets and unearths an old chest that once belonged to his ancestor, François de Hadoque. Inside, he finds the manuscript of his memoirs, which directly echoes the parchment that was found. The adventure is underway.

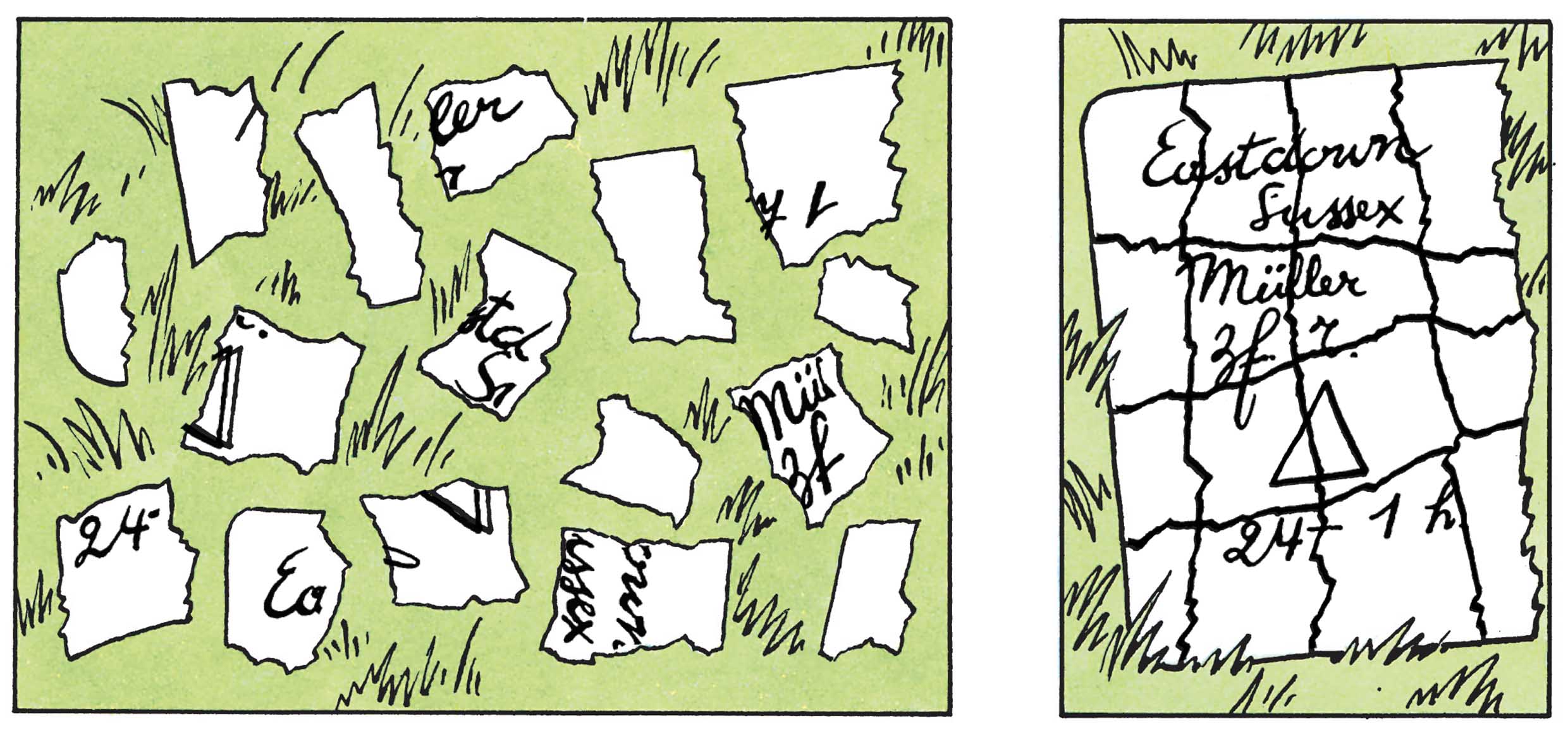

In The Blue Lotus or The Black Island, Hergé repeats the same mechanism. Coded messages, torn scraps of paper, incomplete clues give Tintin a hard time, forcing him to move forward only by piecing things together – sometimes quite literally.

Paper as a trap

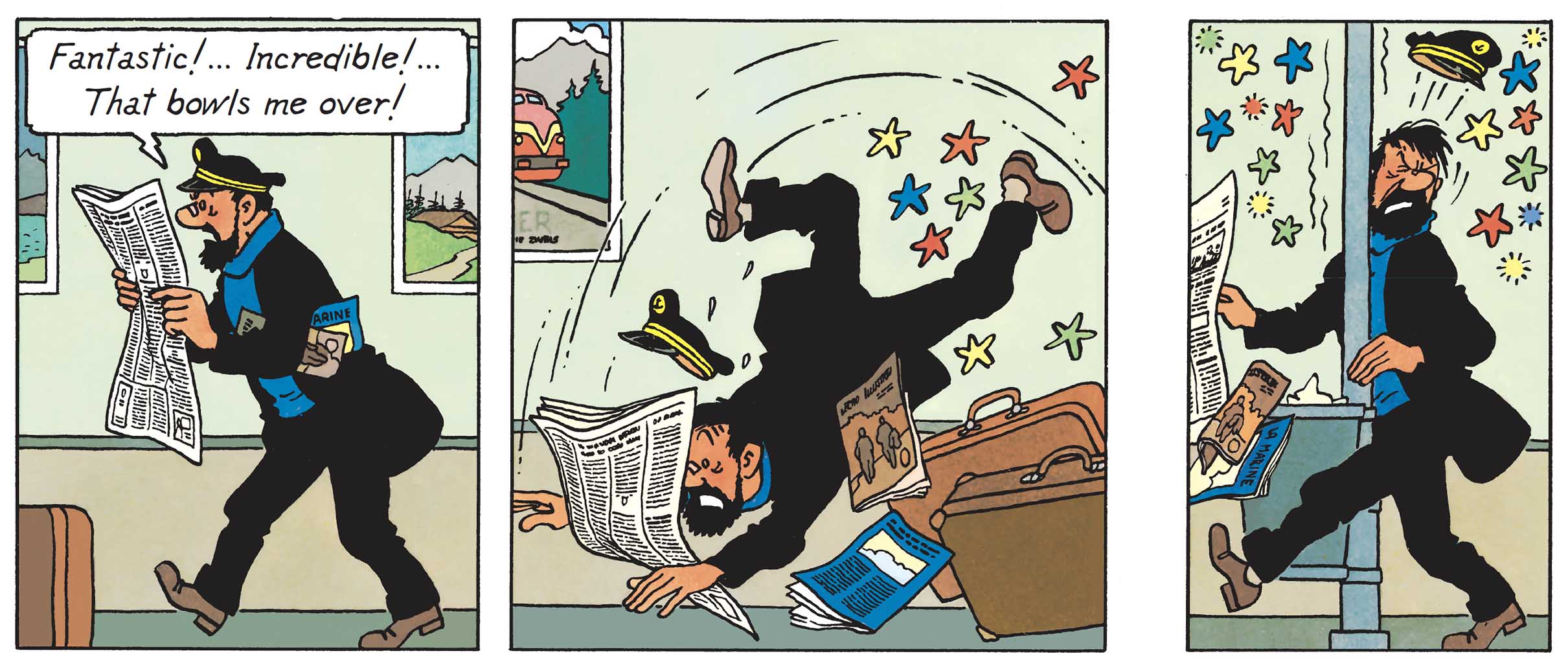

When one is distracted, everything slips! Let it be known: a newspaper can also cause a loss of control. And that is precisely what happens to Captain Haddock, absorbed in his reading at Geneva airport. He trips over suitcases, then over a post. Here, paper is not just a medium in The Calculus Affair. Here, paper is no longer a trigger for action, but a good old comic device. In both cases, the writing distracts attention.

And in Tintin’s very down-to-earth yet explosive world, reading can also be dangerous. In The Secret of the Unicorn, a man hands Tintin a document under the pretext of a formality. Tintin leans in to read it. A accomplice appears behind him and knocks him out with chloroform. The contents of the document hardly matter. After telegrams, letters, envelopes and mysterious seals, the unsavoury henchmen now use paper itself to set a trap for Tintin. Something new? Not really. Tintin has already had his share of trouble in the land of cowboys and Indians.

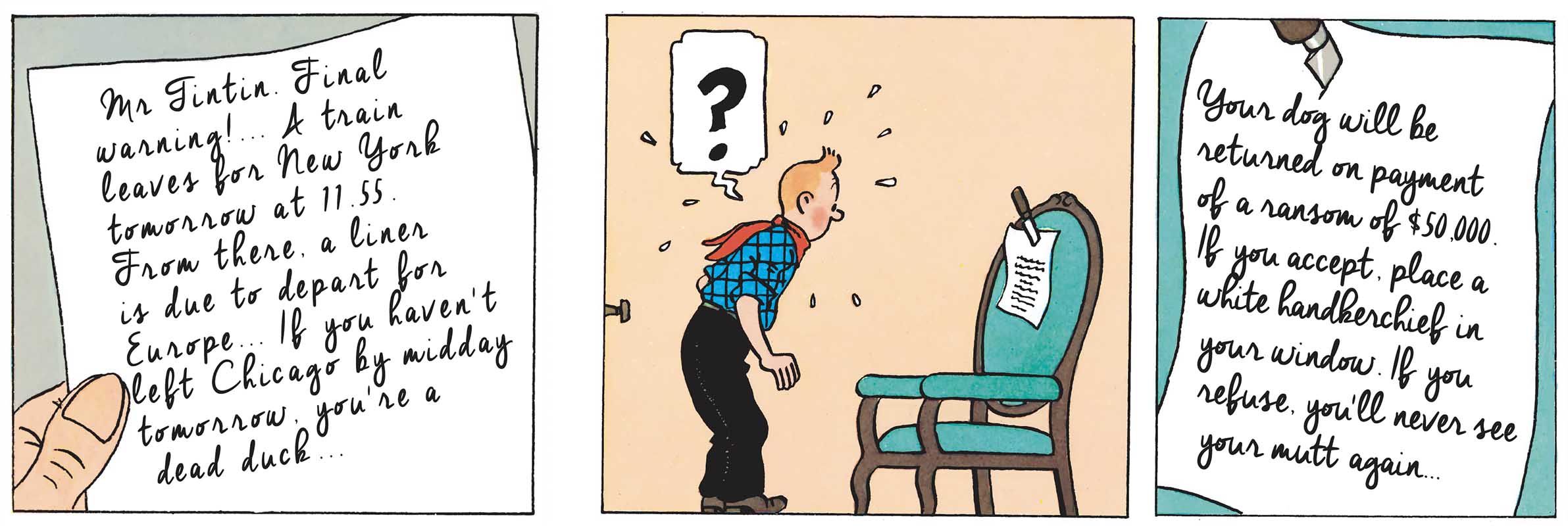

In America, written messages become explicit threats. Tintin receives anonymous letters warning him, intimidating him, or attempting to divert him from his investigation. One of them even announces Milou’s kidnapping. Paper is no longer used to inform, but to establish a power struggle. It does not launch the adventure, it tries to stop it.

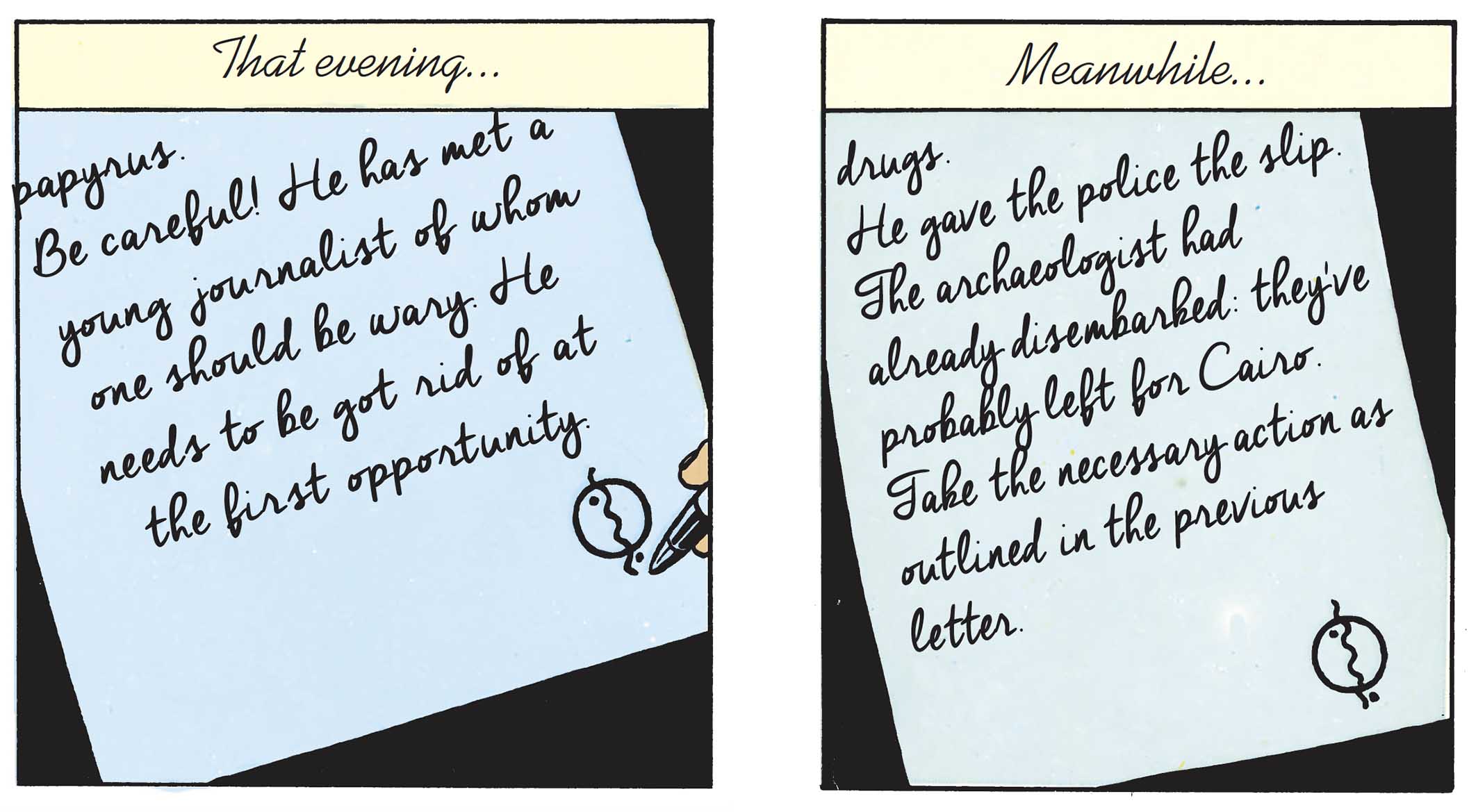

The same device appears in Cigars of the Pharaoh, where letters bearing a sinister symbol announce reprisals to come, and in The Blue Lotus, with fake invitations designed to lure Tintin into traps. In these cases, the message is clear, readable, unambiguous. That is precisely what makes it dangerous. It poses no riddle. It announces an intention, often a hostile and perilous one for our young reporter.

The letter that clarifies the mystery

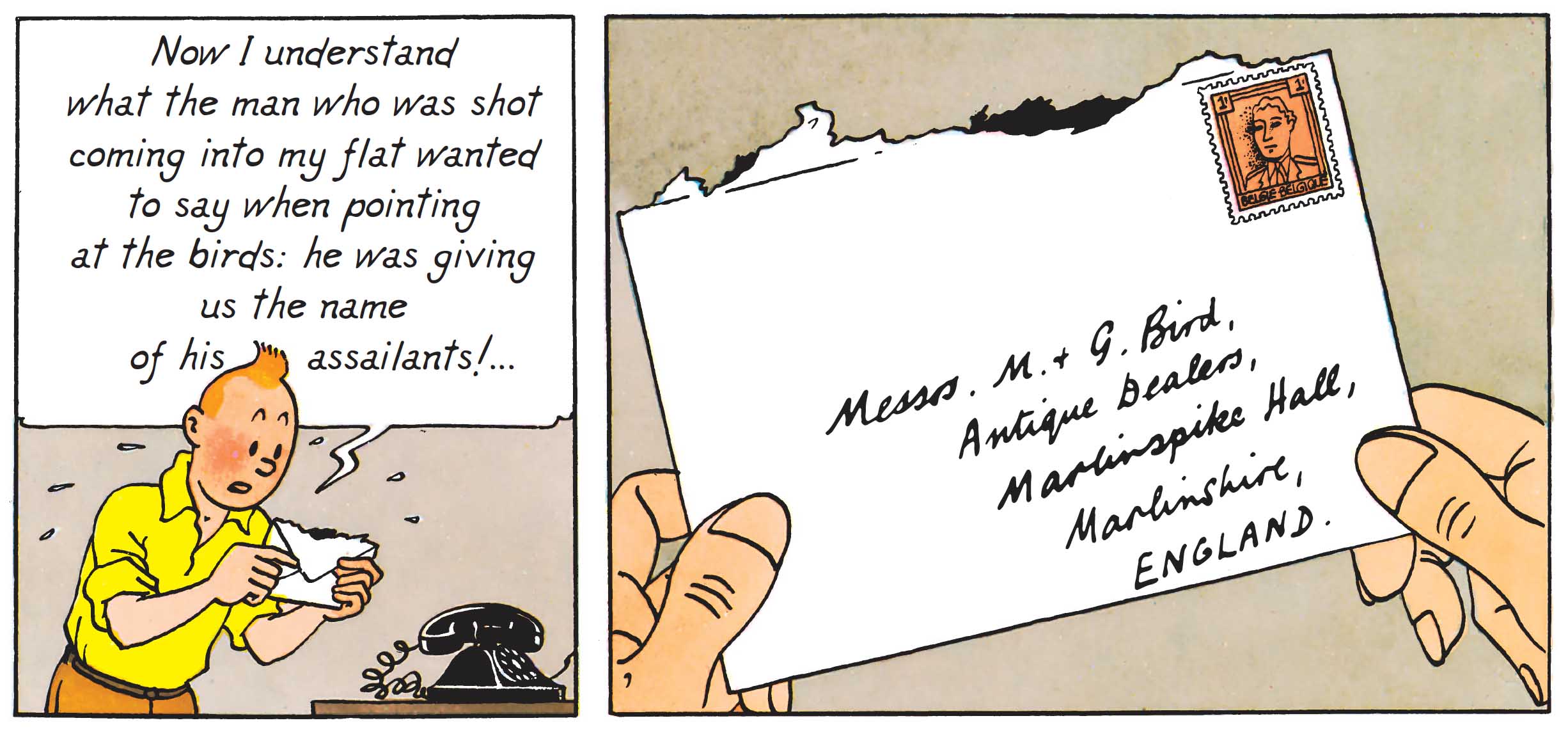

One might think that once launched, the threatening telegram ceases to intervene in the story, but not quite. As we have seen, messages do not only serve to start the adventure. They can also reveal its meaning, and sometimes the depths of the intricate construction devised by Hergé. After untangling many mysteries surrounding the famous Unicorn, Tintin discovers an envelope bearing an apparently ordinary name: Bird Brothers. Looking at it, he suddenly understands what he had previously failed to read.

The man who was shot while returning to Tintin’s apartment was trying to transmit a message. By miming birds, he was not making a random gesture. He was giving a name. The paper adds no new mystery. It retroactively sheds light on an entire scene. To understand it, one had to agree to reread the past.

The press and the message that runs wild

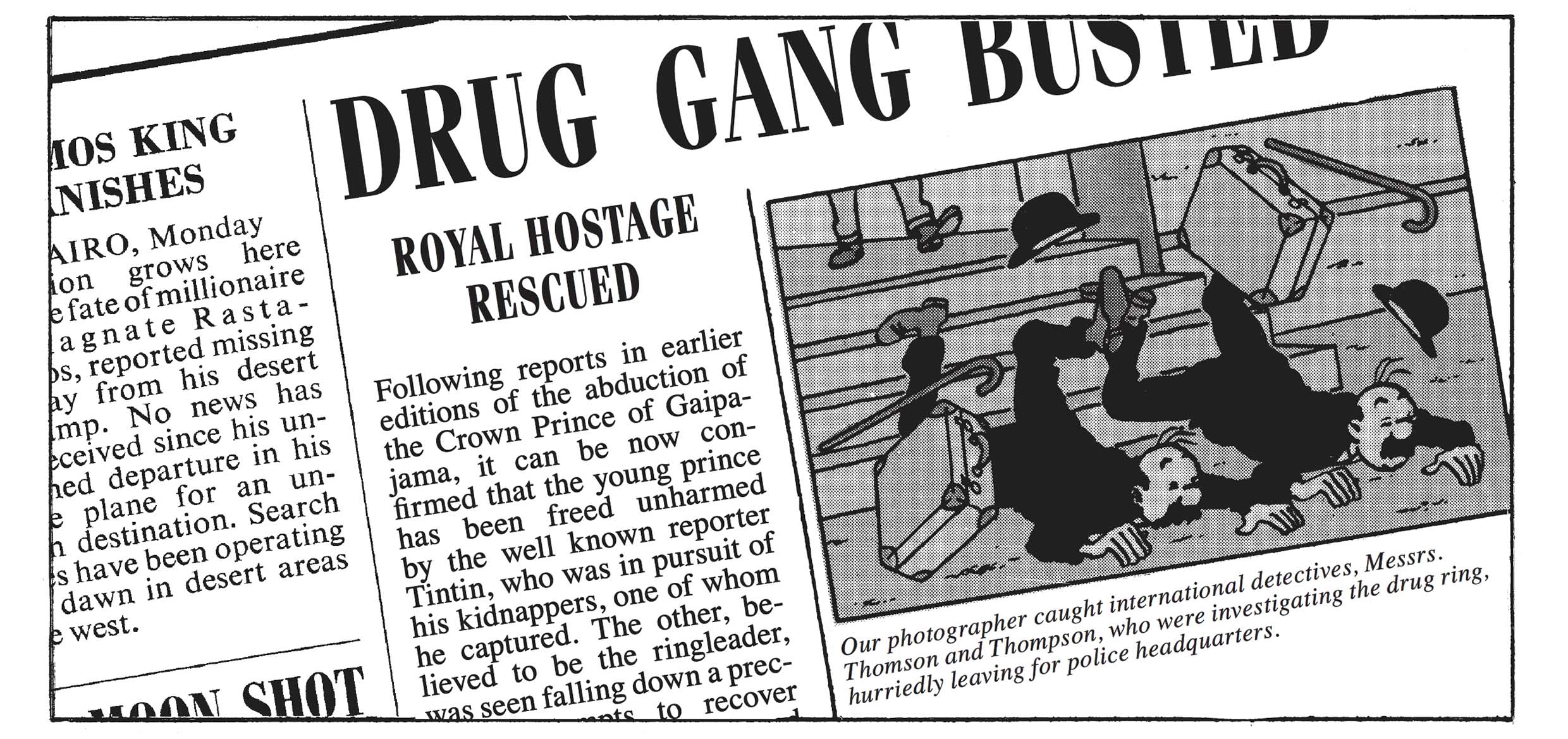

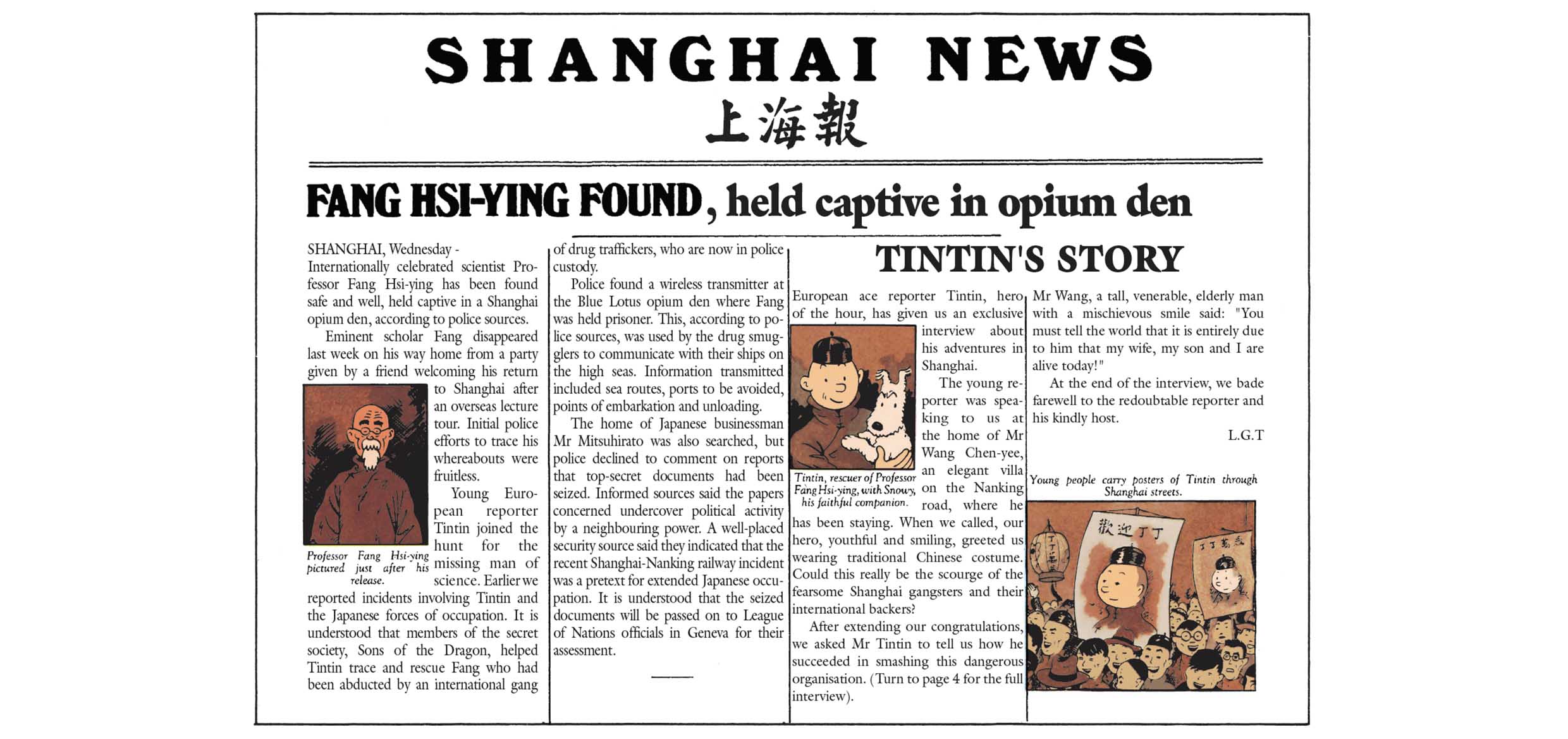

The press follows Tintin like a shadow. It announces his exploits, reports catastrophes, and runs ahead of the facts. In Tintin in America, Cigars of the Pharaoh, The Blue Lotus, The Black Island or The Calculus Affair, newspapers and headlines construct a parallel narrative, sometimes flattering, sometimes dangerous. Printed messages travel faster than information itself, giving as many grey hairs to Tintin’s enemies as to attentive readers.

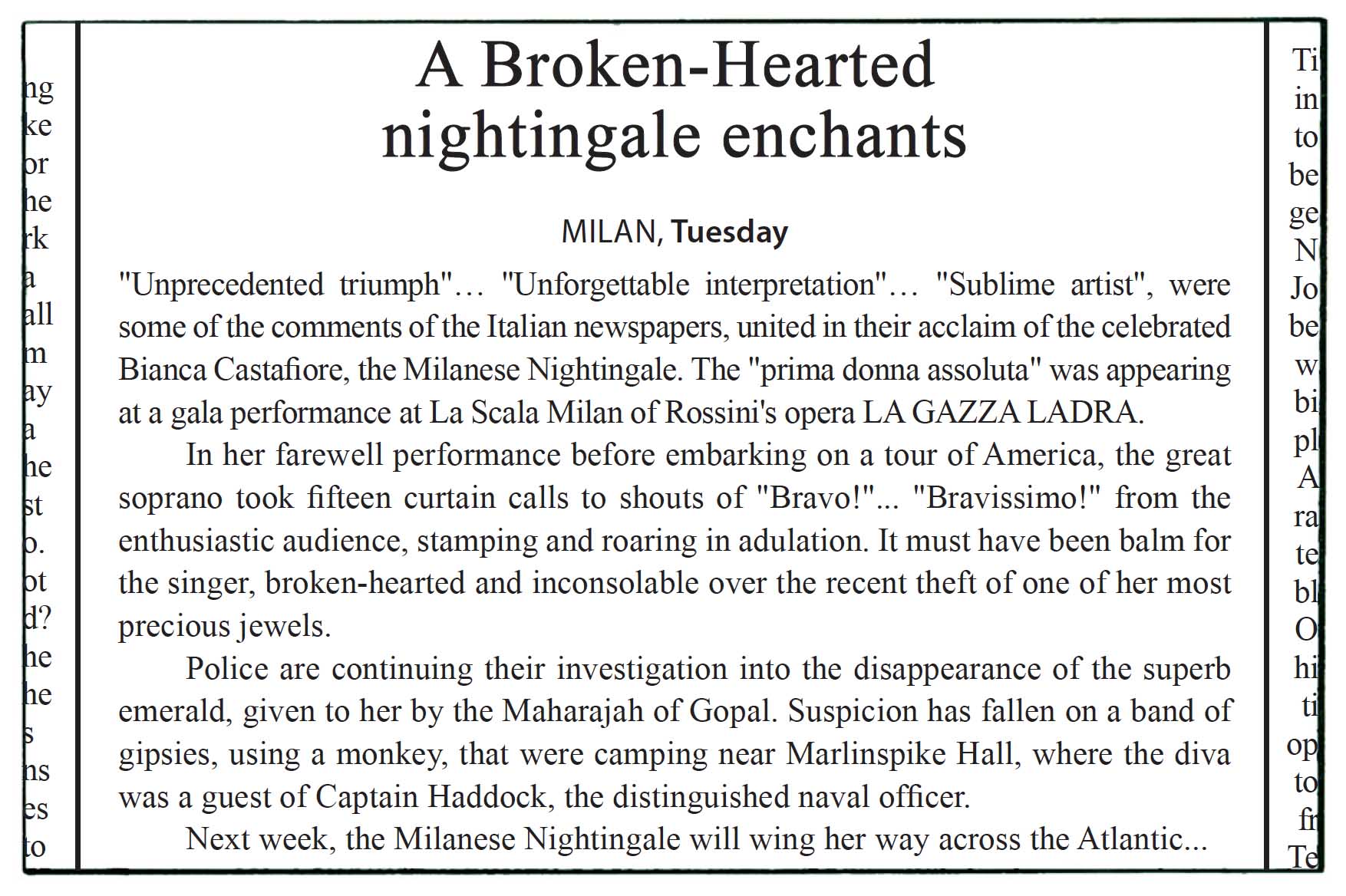

There are also messages that do not seek to deceive, yet end up doing so anyway. The Castafiore Emerald rests almost entirely on this principle. Newspapers report real events, but transform them through shortcuts, repetition and exaggeration. No article is deliberately false, and yet everything becomes wrong.

The rumour takes hold as soon as a telegram from Chester reaches Captain Haddock, congratulating him. The press then claims that the Castafiore is about to marry him. From that moment on, each new article adds another layer, until an event that never existed is fully manufactured. The written word no longer reflects reality; it precedes it, shapes it, and ultimately imposes it.

Conclusion

Is this exhaustive? Not really. Letters, scribbled clues, messages deciphered in Morse code and so on abound in Tintin’s albums, as do encounters stranger than the last. A real treat for methodical readers of every stripe!

Across the albums, one thing becomes clear: Tintin reads a lot. And in Hergé’s world, reading is never neutral. Paper can launch an adventure, obscure it, trap, clarify or ridicule. In a world where everything moves fast, it forces a pause. Tintin unfolds a sheet of paper, and very often, that precise moment is when the trouble begins.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books