Tintin or the Grammar of Gesture

What is the first image that comes to mind when you think of Tintin? The famous blue sweater, the golf breeches, the raincoat… or perhaps all of it at once. But, unconsciously, you probably imagine him in motion, carried by a kind of body language one never forgets.

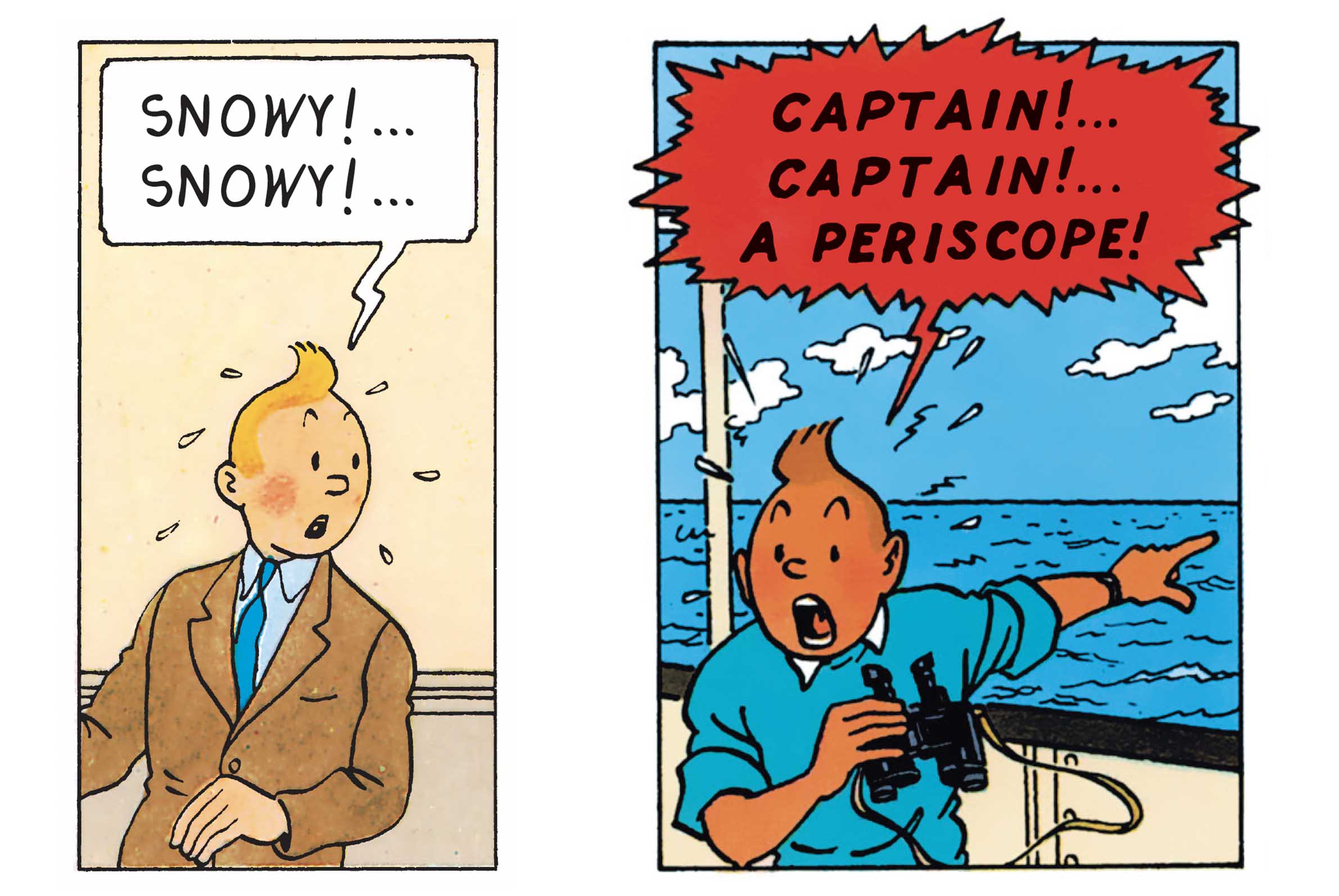

That he may stroll nonchalantly, run like a gazelle and speak plainly is one thing; yet we sometimes forget that the resourceful and perceptive Belgian reporter expresses himself first and foremost through his attitude: shoulders leaning forward, eyebrows arching, hands opening or tightening, a face alive with countless expressions.

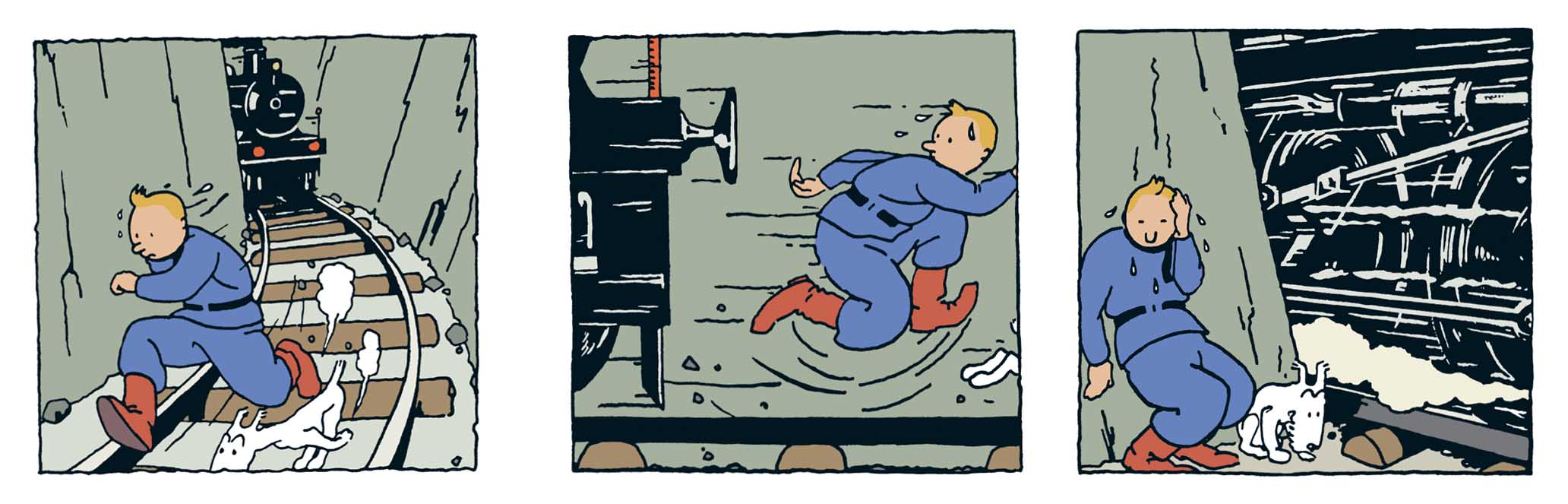

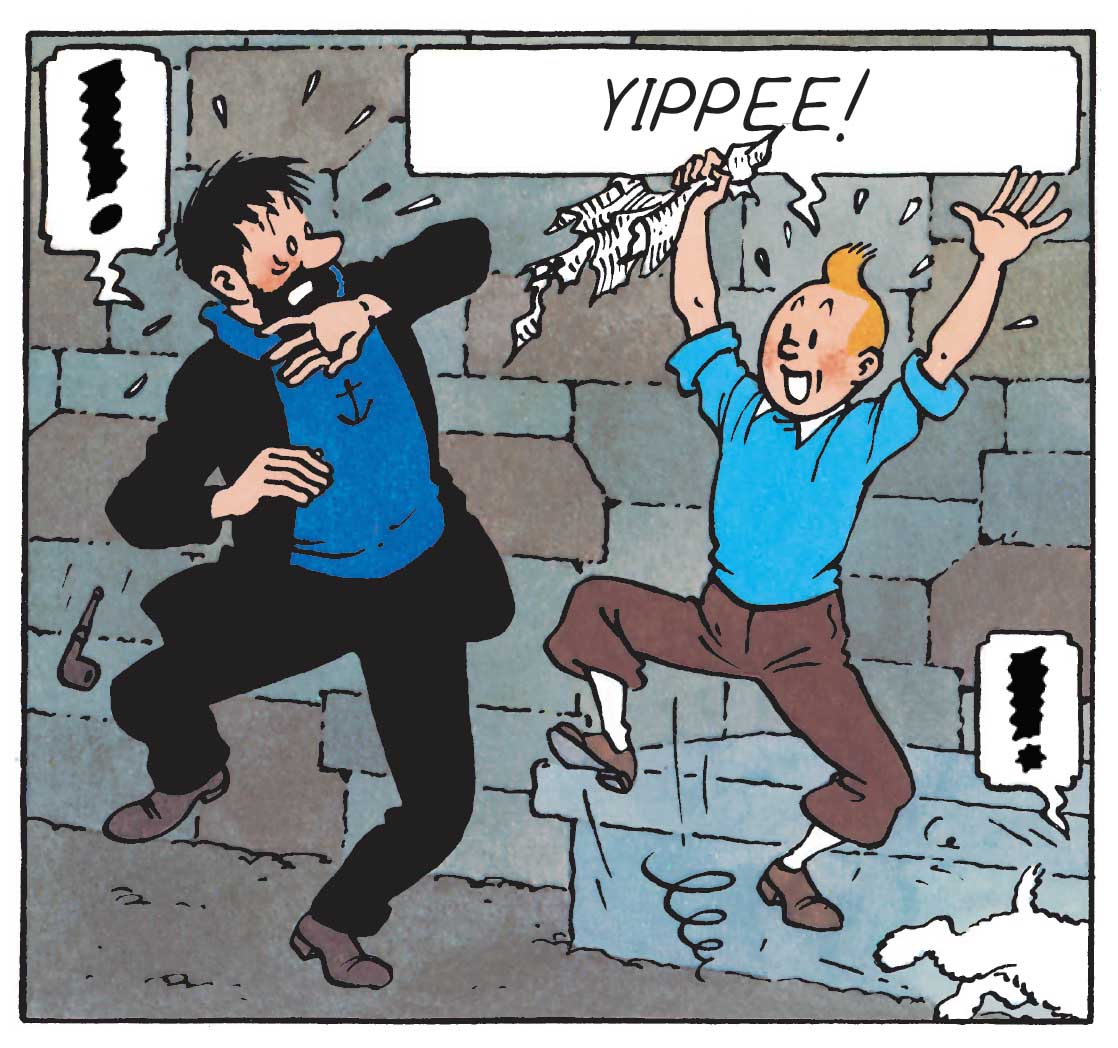

With Tintin, gesture often comes before speech, and sometimes even replaces it. Through rolls, breathless chases, scuffles and all kinds of acrobatics (on land, at sea and even in the sky), he always lands on his feet and sets off again toward his next adventure.

But where does all this energy come from?

At first glance, everything seems almost childishly simple: two dots for eyes, a small round nose, a clean, clear silhouette. In his earliest appearances, the drawing is still quite rudimentary. Then a detail emerges, on the eighth page of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets: the famous quiff, lifted by the wind as he speeds along in an open-top car. It will never fall again. More than a graphic trademark, it is already a movement frozen in time, one that would make its mark on the history of comics.

And this expressiveness did not come about by chance. Hergé himself acknowledged it. If Tintin had a model, he did not have to look far. His younger brother, Paul, had a physical presence, a way of moving, a set of attitudes that had fascinated him for years. He observed him, amused himself with him, absorbed those gestures, so much so that, as he once said, he borrowed from him « his character, his gestures, his attitudes ».

Tintin is therefore not merely an invented silhouette: his body language comes from a real body, observed, memorized and then transposed into drawing.

Hergé did not simply draw characters; he sought to give each one a convincing physical presence. He drew inspiration from gestures and attitudes observed directly in life, while maintaining strict control over the postures of his characters. At the Hergé Studios, assistants worked on the settings and environments, but Hergé himself drew the main figures and ensured the accuracy of every pose.

This restraint gives Tintin a singular expressiveness. Surprise is conveyed by widened eyes and a slight tilt of the torso; fear, by a step aside and a tense arm; determination, by a suddenly upright, compact stance, ready to act. Even stillness becomes eloquent: bent over a clue, crouched in the dust, frozen before a discovery.

This language of the body is all the more important because Tintin is, at heart, a hero born of scouting. All of this is first read in his posture. Even action follows the same logic: chases, falls, fights… nothing is chaotic. Movement is clear, directed, almost pedagogical. As one watches him live within the panels, a certainty emerges: Tintin’s movements tell the story just as surely as the dialogue.

So, is Tintin an actor made of paper? In a way, yes. But an actor of a rare school: no spectacular gestures, no exaggerated effects. Only attitudes that are thought out, observed, repeated until they become self-evident. Perhaps it is here, even more than in his exploits, that his timelessness resides.

In this month of January, when his birth is celebrated, it is worth remembering that if Tintin continues to speak to us across generations and languages, it is not only through what he says… but through the way he stands, leans, stops or sets off again. A universal language that still resonates today, beyond all borders.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2026

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books