The Speaking Vignette: The Skyward Emergence

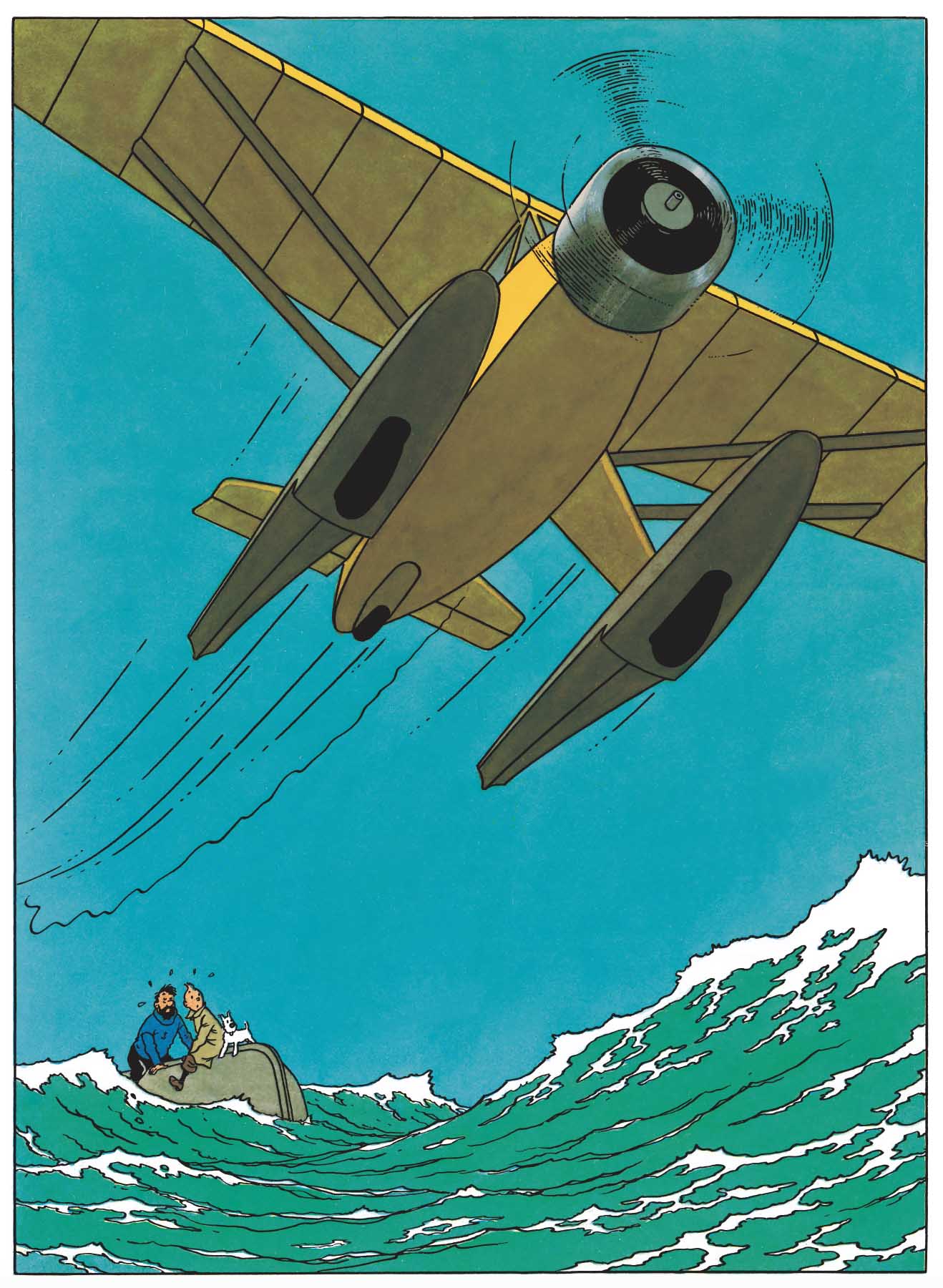

On a boat tossed by the waves, Tintin, accompanied by a gruff captain he has just met for the first time, faces the empty horizon and mounting exhaustion… before an aircraft suddenly appears in the sky! In The Crab with the Golden Claws, Hergé stages Tintin and Captain Haddock on a lifeboat, as a seaplane passes above them.

This image, which left a lasting impression on many readers, is a vignette of rare richness, in which one can read at once the work of staging, documentary rigor, and the successive adjustments of the drawing.

At first glance, the scene seems simple: a sea, a boat, an aircraft. Yet, as so often with Hergé, this simplicity is deceptive. Each element is the result of a precise choice and careful observation of reality. The aircraft flying over the castaways is neither imaginary nor a patchwork of several models: it is a Bellanca 31-42 Pacemaker, an American civilian seaplane from the 1930s, recognizable by its floats and the line of its fuselage. Hergé does not merely allude to aviation; he reproduces its forms with near exactness.

The lifeboat itself reflects the same documentary concern. Its silhouette, the placement of the figures, the situation of drifting at sea all draw inspiration from a real rescue photograph: that of the survivors of the liner Georges Philippar, which sank in 1932. In other words, the fictional image is built upon an archival one, and the adventure is drawn directly from reality.

Imagine the work of documentation required to achieve such a level of realism, which is nevertheless anything but decorative. But even more striking is the choice of angle. Hergé pushes this logic further in his page composition. For between the first version and this one, the vignette is reworked: the aircraft’s diving attack is now depicted from a low angle. This simple change of viewpoint alters the perception of the scene: the plane becomes more massive, more overwhelming, yet nevertheless less frightening, while the boat appears even more fragile. In the end, framing itself produces emotion, so much so that the image remains vividly memorable even today.

It introduces the events that are to follow: the confrontation with the plane’s occupants, the improvised escape, then the storm that disorients the aircraft and the captain’s reckless gesture, all leading inevitably to the crash in the desert. Over just a few pages, Hergé shifts his characters from one unstable environment to another, from sea to sky, and from sky to sand. Tintin, it seems, repeatedly falls from Charybdis into Scylla – in other words: from bad to worse – in his adventures.

In this sense, this vignette does not merely illustrate a scene of adventure. It reveals, in a single image, Hergé’s work, his documentary precision, his choice of framing, and the way a simple retouch can transform the reading of a scene.

There would still be much more to say, but that will be for another time. The resolution, meanwhile, can be found in... The Crab with the Golden Claws.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2026

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books