Tintin, a Reporter Without a Pen

When Tintin first appears in Le Petit Vingtième on January 10, 1929, Hergé immediately assigns him a clear profession: he will be a reporter. And yet there is a catch: Tintin is a journalist who almost never writes.

The very first panel of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets does not show any drawing at all. Only text:

A solemn, almost administrative departure, which anchors the character in journalism long before plunging him into the adventure as we know it today.

Yet this vocation as a reporter is as much fantasy as reality. Fascinated by the stories of great travelling journalists such as Joseph Kessel and Albert Londres, Hergé dreamed of “investigating in the field” without ever undertaking such journeys himself. Tintin would fulfill in his place this calling as a full-time globetrotter.

The paradox is clear: Tintin is officially a reporter for a large part of the series (the early albums are even subtitled The Adventures of Tintin, Reporter), but he actually practices his profession only once, in the founding story.

In Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, he writes a single article, that’s true. The rest of the time, he causes events rather than describing them. A real Speedy Gonzales of information, always already gone before even having the time to write it down.

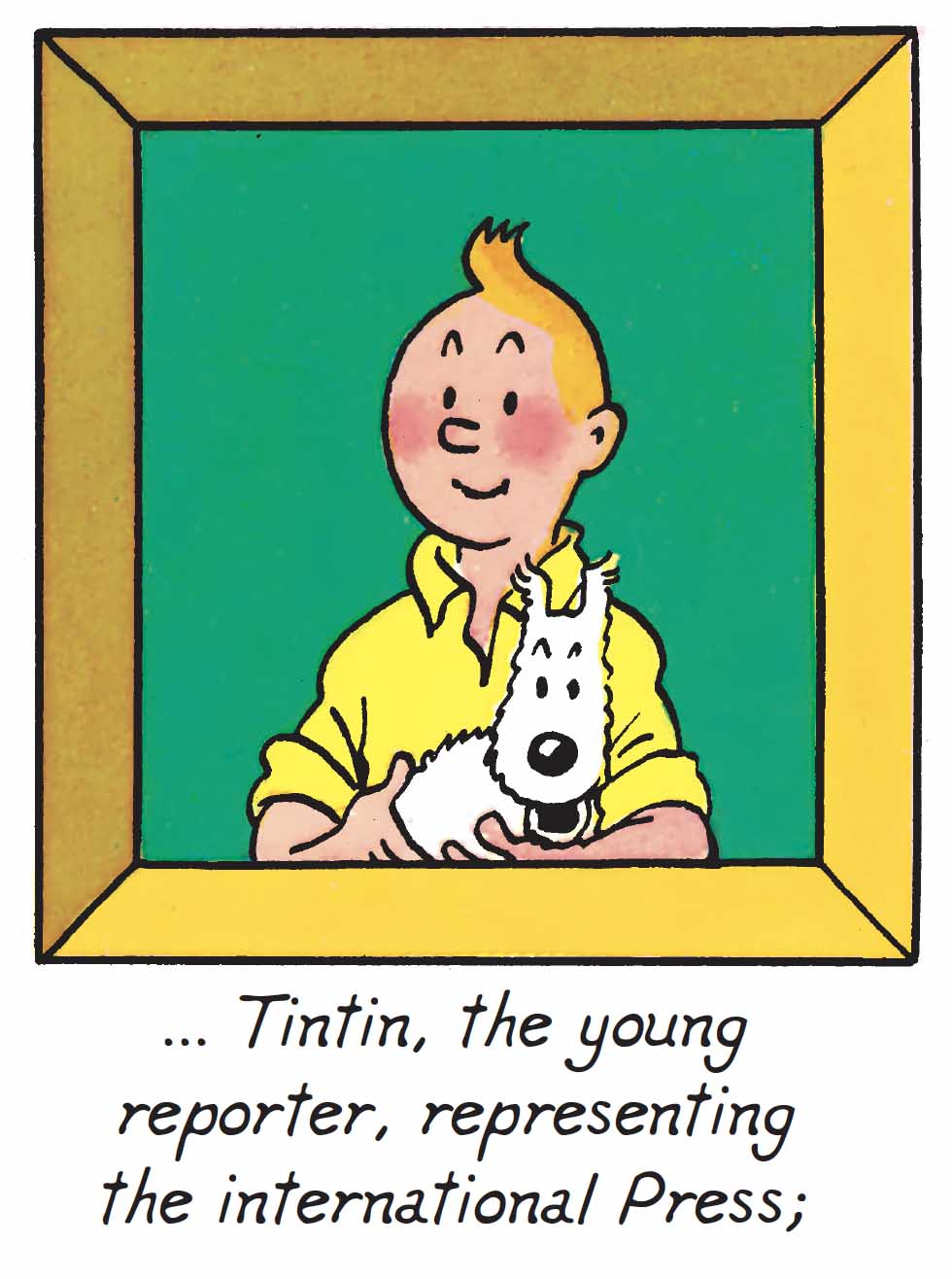

Even when Hergé occasionally reminds us of his journalistic status (in The Shooting Star, it is stated that he « represents the press »), Tintin takes no visible notes, carries no notebook, and adopts no true observer’s posture. He leaps into action, launches into chases, gets into improbable fistfights, and leaves the report itself offstage. With Tintin, information is not written, it is lived.

Hergé himself seems aware of this discrepancy.

In one panel, Le Petit Vingtième ironically certifies the authenticity of photos « taken by Tintin himself, assisted by his friendly dog, Snowy. » A kind of private joke about this reporter who piles up evidence without ever delivering a real written report.

Tintin sets off. That is his very first gesture, his act of birth. « Where to? » one wonders as early as 1930, faced with a gigantic globe of the world. Not everyone can be Palle Huld.

And what if this Tintinesque paradox reminded us, indirectly, of the value of the act of writing itself? At a time when the keyboard has replaced the pen, World Handwriting Day invites us to rediscover precisely what Tintin himself has almost always left offstage.

For writing by hand is not just a nostalgic reflex. It is an act that is profoundly beneficial for the brain.

Research carried out notably by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) shows that handwriting activates much broader and more interconnected brain networks than typing on a keyboard. In experiments conducted with young adults, researchers observed that far more extensive neural networks are engaged when people write by hand, whereas only more limited areas are activated when they type.

Better still: these brain regions communicate with one another via waves associated with learning and memory. The result? Information written by hand is better encoded, better understood… and better retained. This is the one adventure in which you can outdo Tintin!

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2026

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books