What if Tintin had never existed?

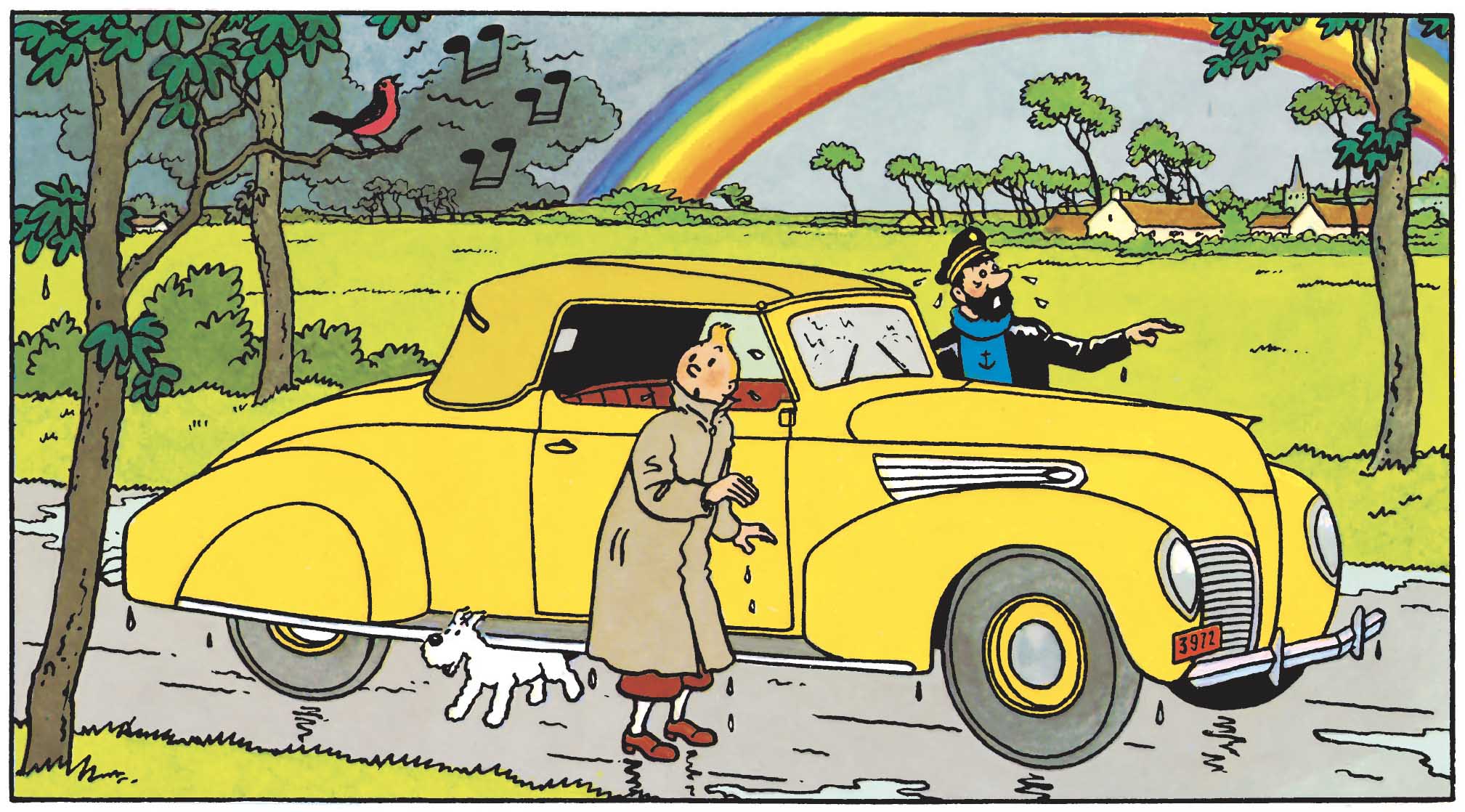

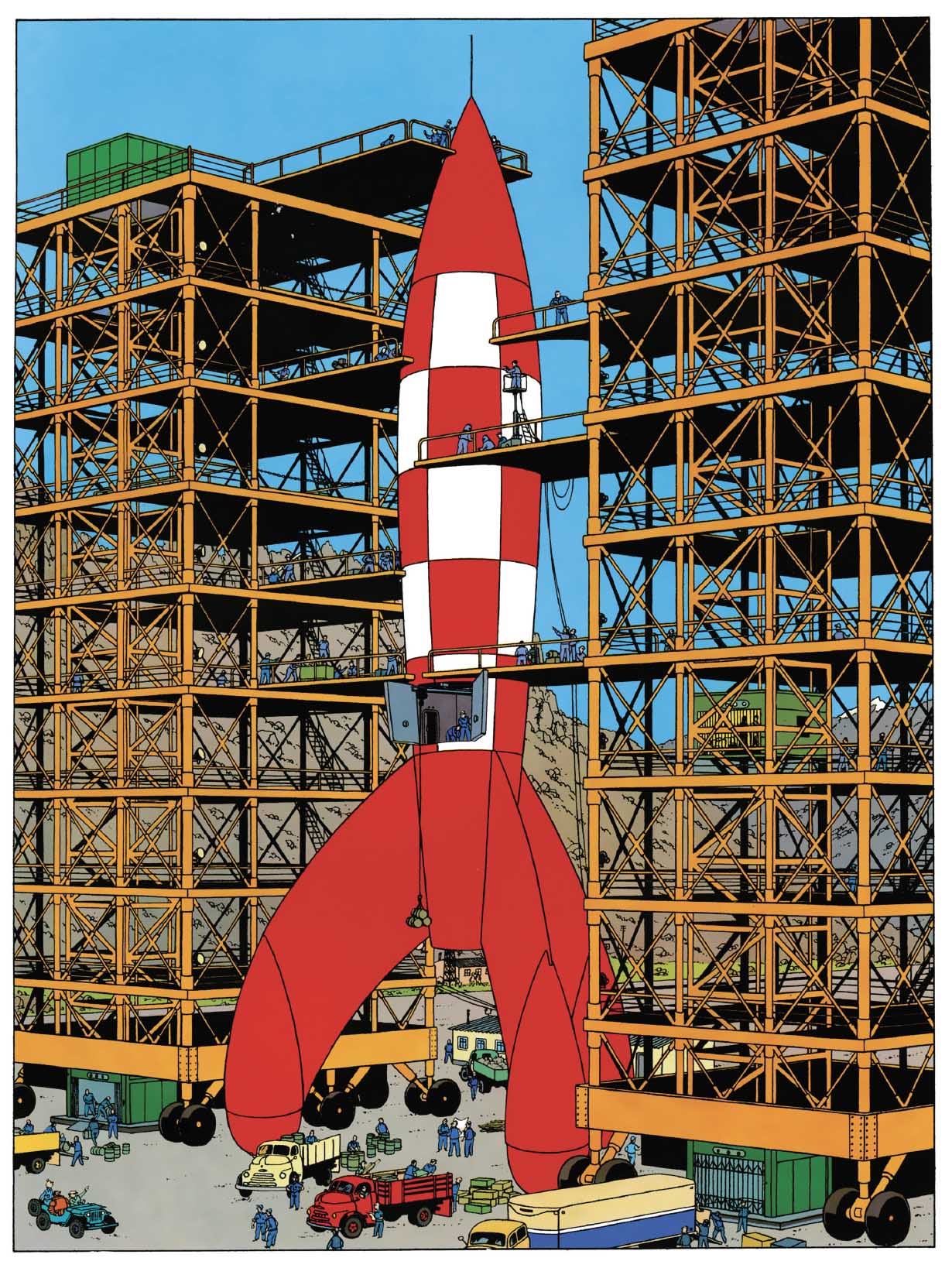

What would remain if Tintin had never existed? The question may seem far-fetched… and yet: a world without Haddock, without Snowy, without Professor Calculus. And more still! Without Marlinspike Hall, without gripping investigations, without frantic chases, without Tchang, without a lunar rocket, without a yeti. So many images, figures and scenes that instantly spring to mind, having shaped our collective imagination.

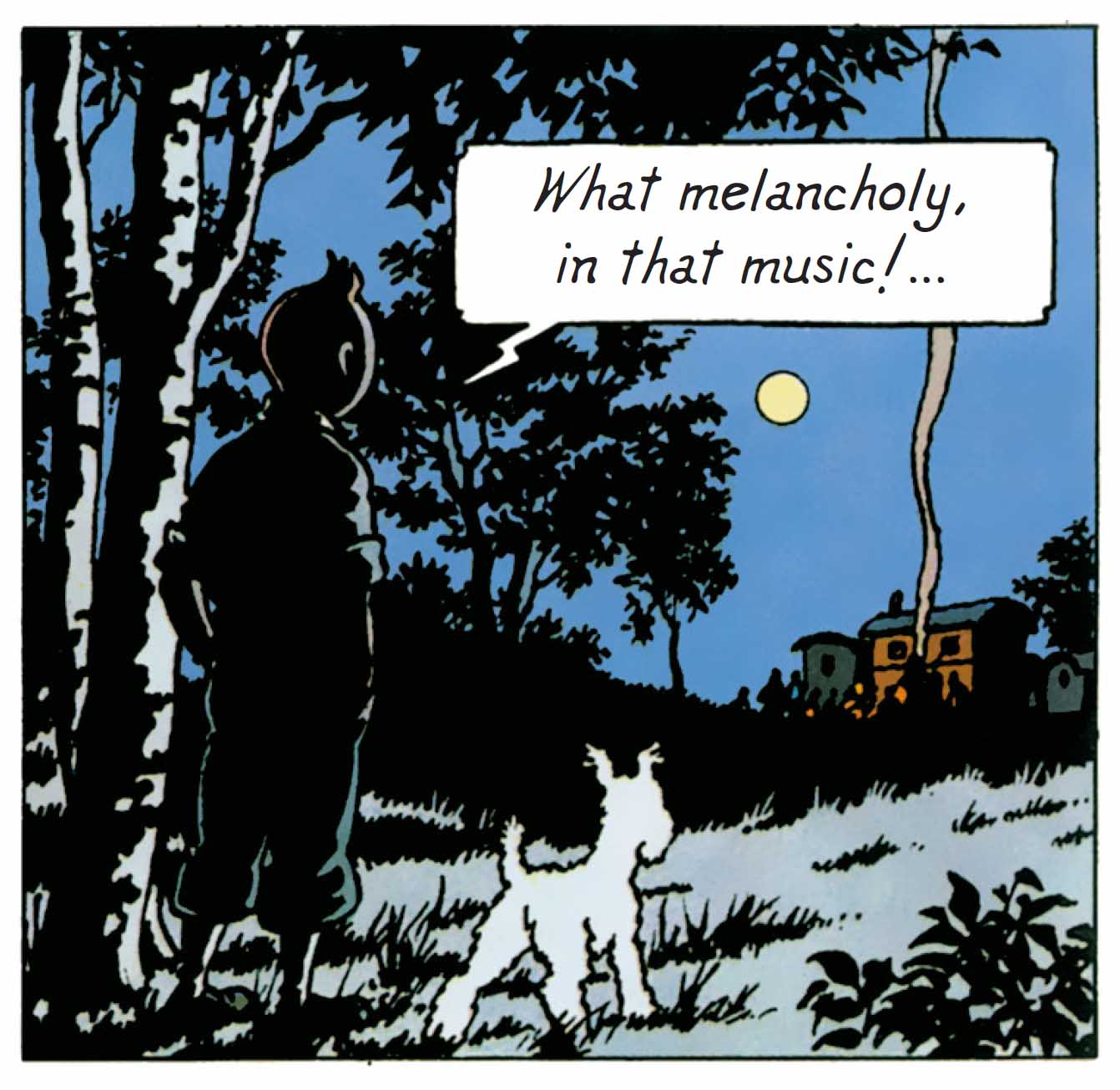

Born more than ninety-seven years ago, Tintin nevertheless continues to accompany readers of all generations with remarkable freshness. As this anniversary approaches the brink of a centenary, the time has come to step back, to leaf once more through the albums, and to ask ourselves what comics would have lost without these images, these moments and these motifs, now impossible to forget…

Back to the future

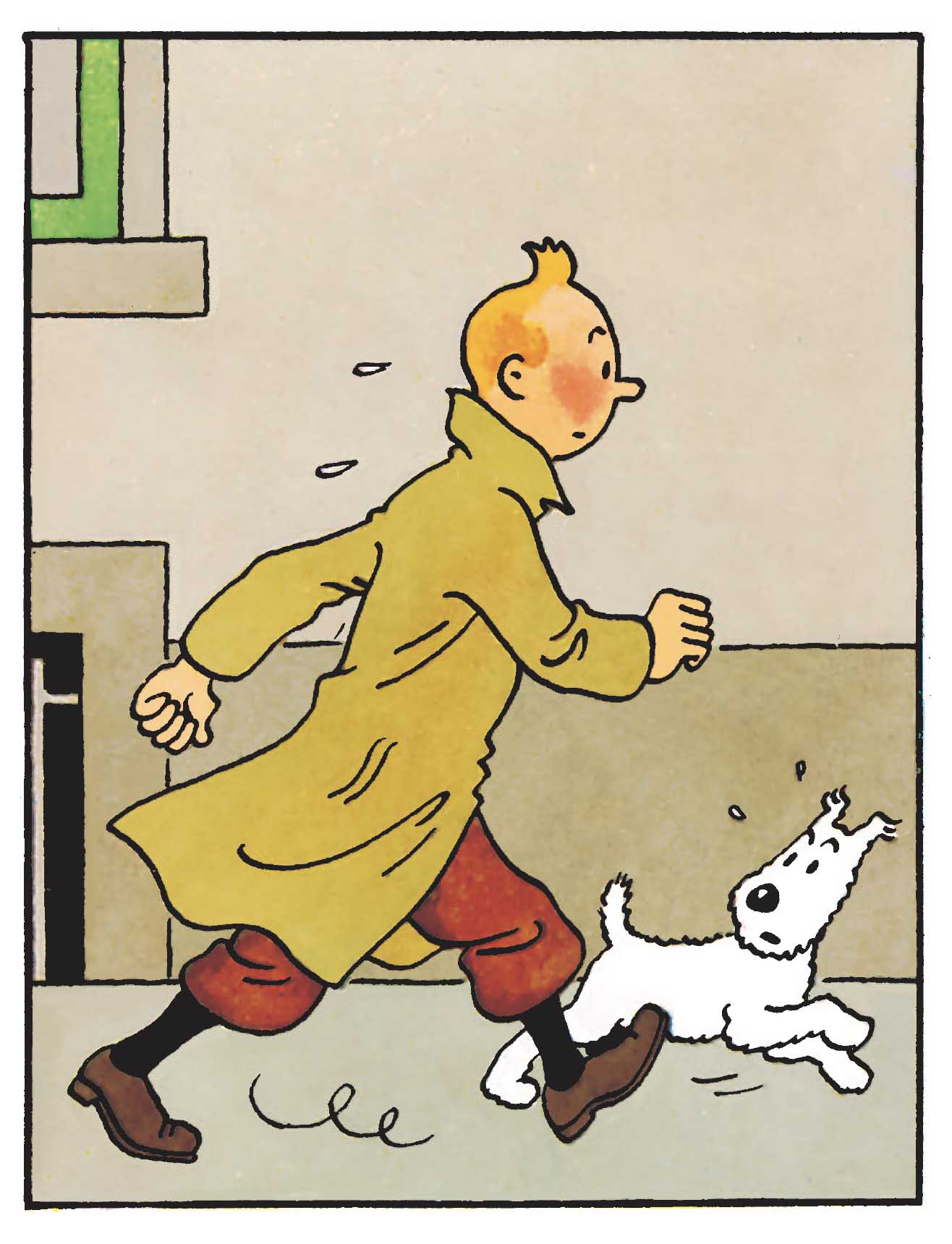

Imagine for a moment that on January 10, 1929, Tintin had never appeared. It would not simply mean one less quiffed hero, but the disappearance, all at once, of an entire series of foundational images and scenes. In Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, he would never have revealed that raw, youthful energy, the kind that, from the very first pages, propels him toward the reader like a rocket.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, in Tintin in America, we would never have seen him confront an aggressive, mechanical modernity, surrounded by Native Americans and thugs of every stripe, ready to brawl at the slightest misstep. And with The Shooting Star, we would have missed that shift toward scientific uncertainty, that precise tension between curiosity, competition and collective anxiety, as though the weight of the era itself bore down on the expedition.

Later on, the absence would become even more pronounced. Without Tintin, the imaginary kingdom of Khemed would lose its unflinching look on trafficking and hypocrisy, realities no simple action story could fully conceal. And with Tintin and the Picaros, we would never have witnessed that distinctive dissonance: an unchanging hero moving through a world grown murkier, more political, sometimes disenchanted. Perhaps that is the most striking aspect of this anniversary thought experiment: Tintin does not truly age, but everything he passes through does. Erase him, and you remove not just a silhouette, but a way of telling the twentieth century in motion.

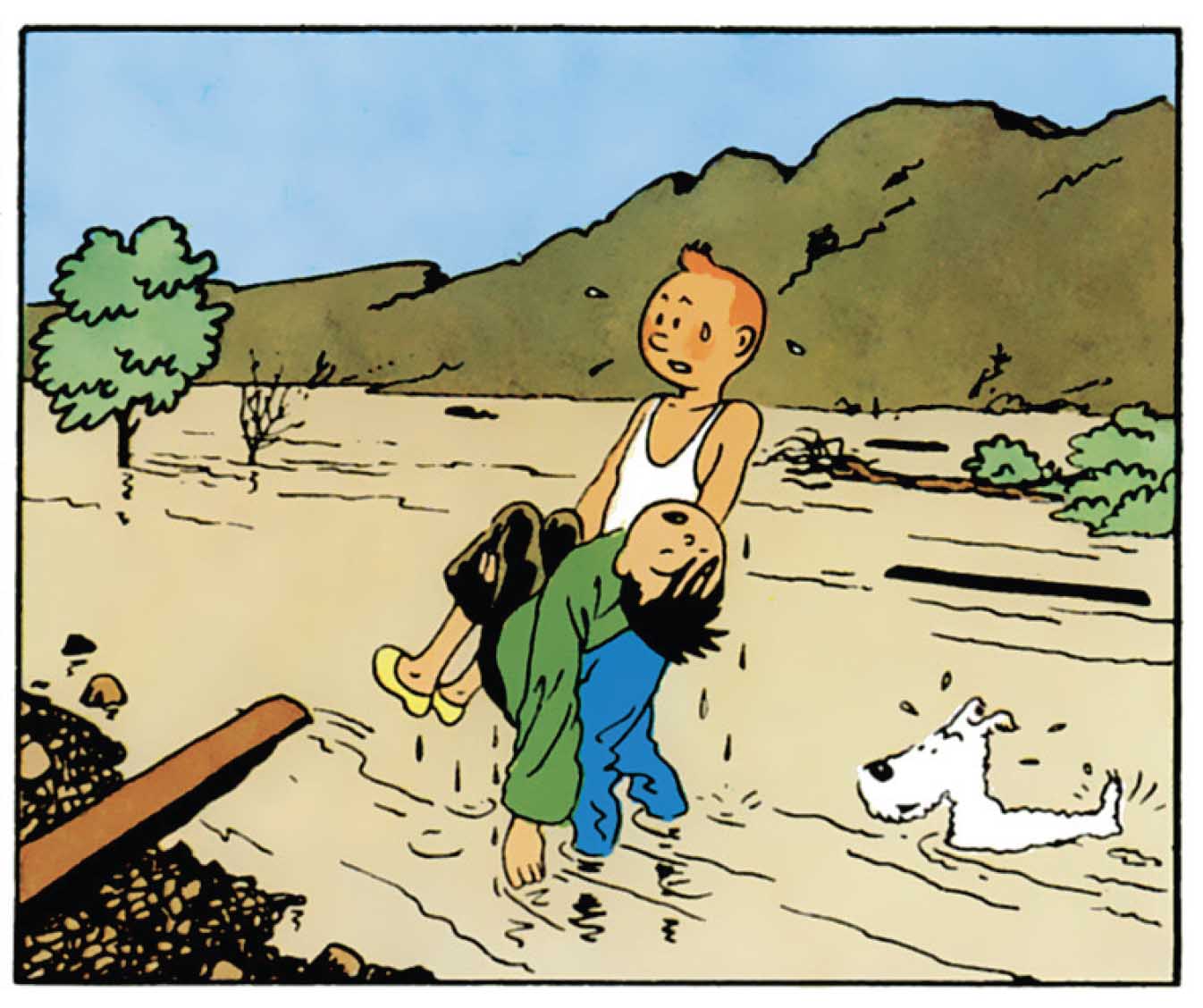

Tintin’s greatest rescues

Among the feats that would never have existed, rescues nonetheless occupy a central place. They are never mere spectacular twists; they often form the moral core of the story. The most famous is undoubtedly the rescue of Tchang, pulled from a snowy ravine in Tintin in Tibet, through an almost reckless determination, with Tintin acting without calculation or reward.

But many other rescues punctuate the series: Captain Haddock hauled from danger time and again, Professor Calculus freed from his captors, the Thompsons extracted from absurd predicaments, and so on. Tintin does not triumph through strength, but through loyalty, perseverance and a refusal to abandon others. Had Tintin never existed, these images too, these gestures of rescue, repeated album after album, would be sorely missed. Imagine our dismay…

The images that made Tintin

Like many others, certain panels shaped Tintin far beyond their original albums. They have crossed generations, fixing postures, silhouettes and situations inseparable from his universe. How could one tell a fictional story of space exploration without invoking the red-and-white rocket from Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon, now a universal symbol of scientific adventure?

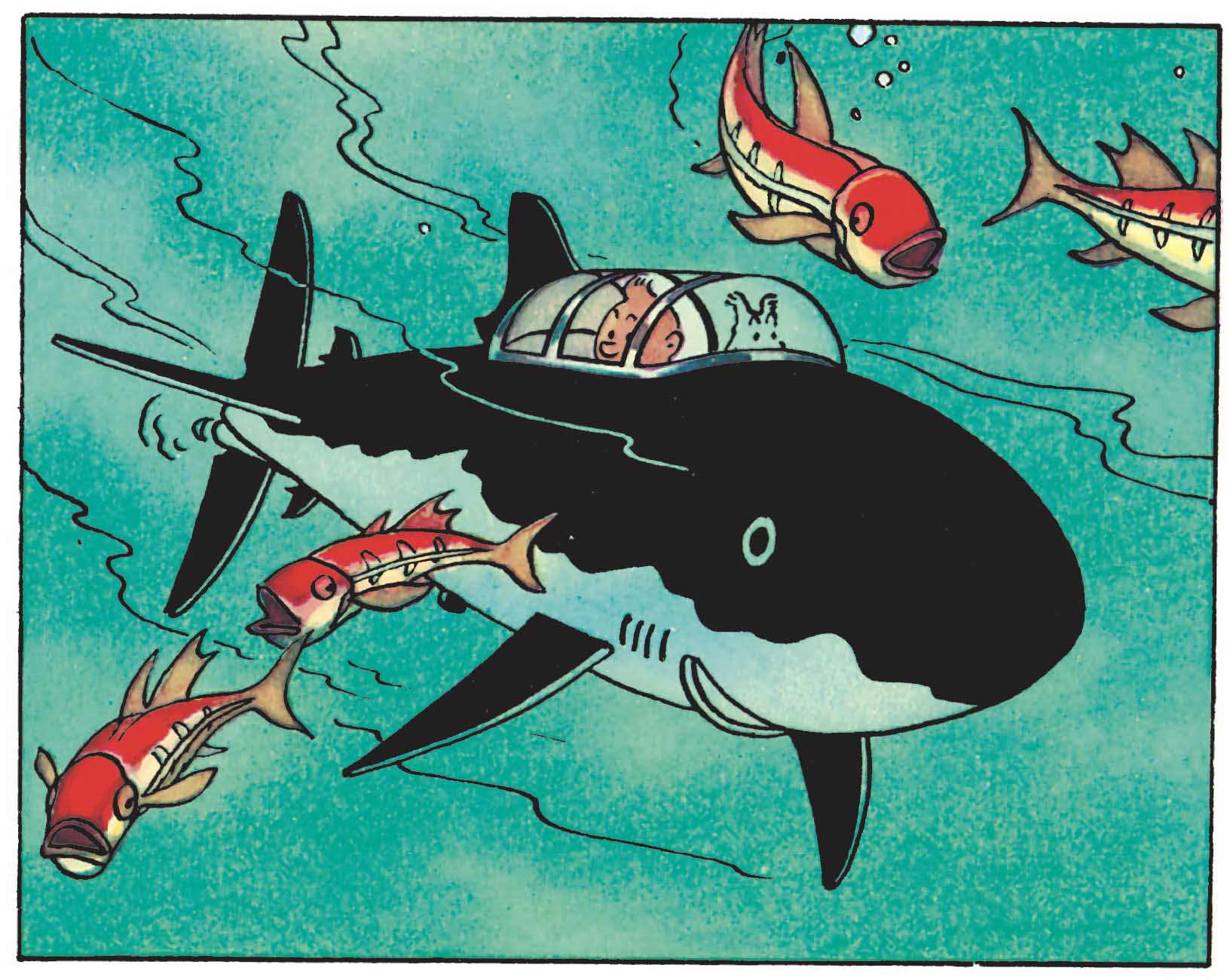

The silent face-off with the yeti in Tintin in Tibet offers a powerful image that runs counter to spectacle. The shark seen from below in Red Rackham’s Treasure, the airplane bursting from the sky in The Crab with the Golden Claws, or the diva frozen mid-aria in The Castafiore Emerald.

These images have imprinted a visual memory that is instantly recognizable. Remove Tintin, and it is not just albums that vanish, but an entire repertoire of simple, legible images that became foundational to the history of comics.

Tintin’s atypical characters

Tintin’s universe would not hold together for long without its secondary characters. First among the missing would be that improbable scientist, already mentioned earlier: Professor Calculus, stone-deaf, distracted, whose inventions advance the plot as much through absence and misunderstanding as through genius.

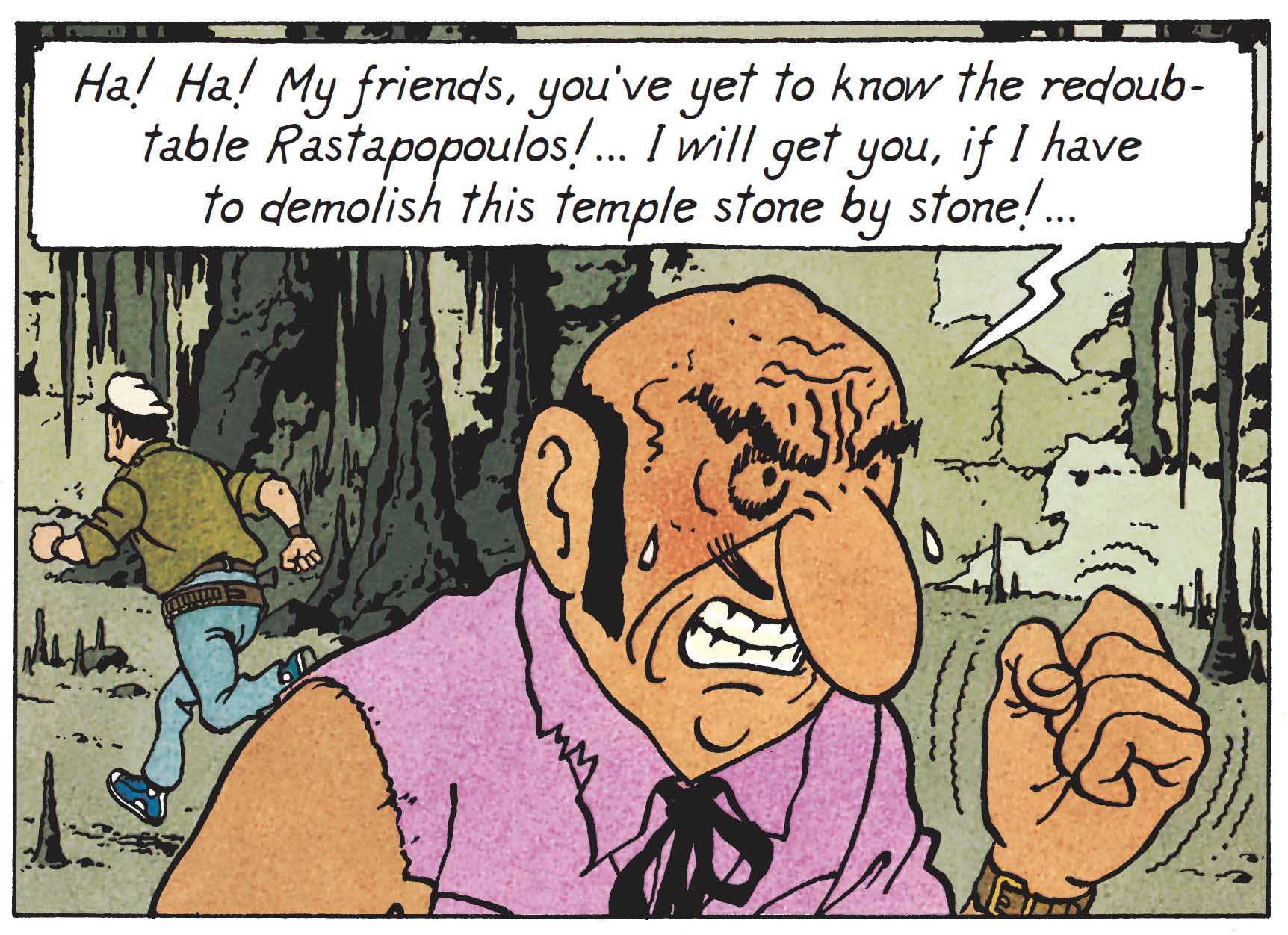

There would also be no overbearing Bianca Castafiore, capable of upending an entire narrative (and driving Haddock mad) by the sheer force of her voice. Without Thomson and Thompson, those absurd breathing spaces that regularly defuse tension would be lost. Even the villains would suffer: without figures like Rastapopoulos (more manipulative than brutal) evil would become distinctly less entertaining.

These atypical characters are not satellites. They form a contrasting human gallery, sometimes excessive, often touching, which gives Tintin its depth and rhythm. Without them, the adventure would be more linear, colder. With them, it becomes unpredictable, alive, profoundly singular. And Haddock won't say otherwise!

Images of danger

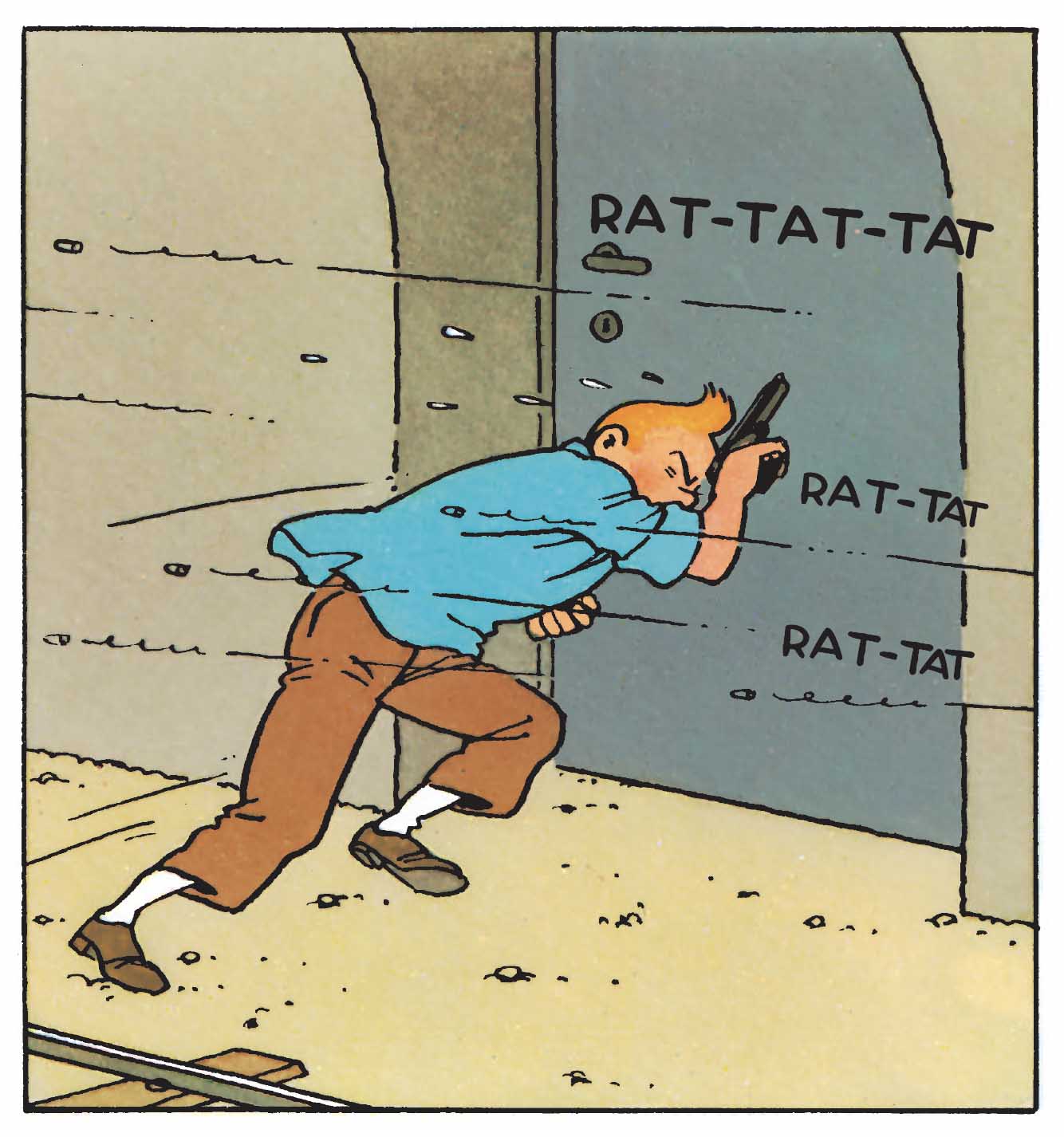

Danger is one of the most constant visual engines in Tintin’s universe. Without it, a large part of the grammar of modern adventure would be missing. Hergé multiplies extreme situations (falls, explosions, chases, near-drownings) always with perfect clarity.

Certain images have endured. Tintin hanging over the void, clinging to an icy cliff in Tintin in Tibet; confronting the fearsome yet strangely endearing Ranko in The Black Island; threatened by explosions or invisible weapons in The Calculus Affair; or submerged underwater, surrounded by sharks, in Red Rackham’s Treasure.

These images of danger avoid excess and escalation. Faithful to the clear line, without shadowing or overwrought dramatization, Hergé builds tension through framing, body positioning and clarity of action. Danger is immediate, readable, almost methodical. Remove Tintin, and what would be lost is not just a set of thrills, but a true lesson in visual storytelling, passed down album after album. And on that front, there is no doubt: Hergé knew exactly what he was doing.

Places that shaped the adventure

Places are never mere cardboard sets, Potemkin villages, in Tintin’s adventures. They shape the narrative, dictate its rhythm and impose their rules on the characters.

The crushing desert of The Crab with the Golden Claws, the strange, almost paranormal environment of Flight 714 to Sydney, the suffocating jungle of The Broken Ear, or the labyrinthine streets of The Blue Lotus… each environment imposes its own tempo, its way of moving, waiting, fleeing or resisting.

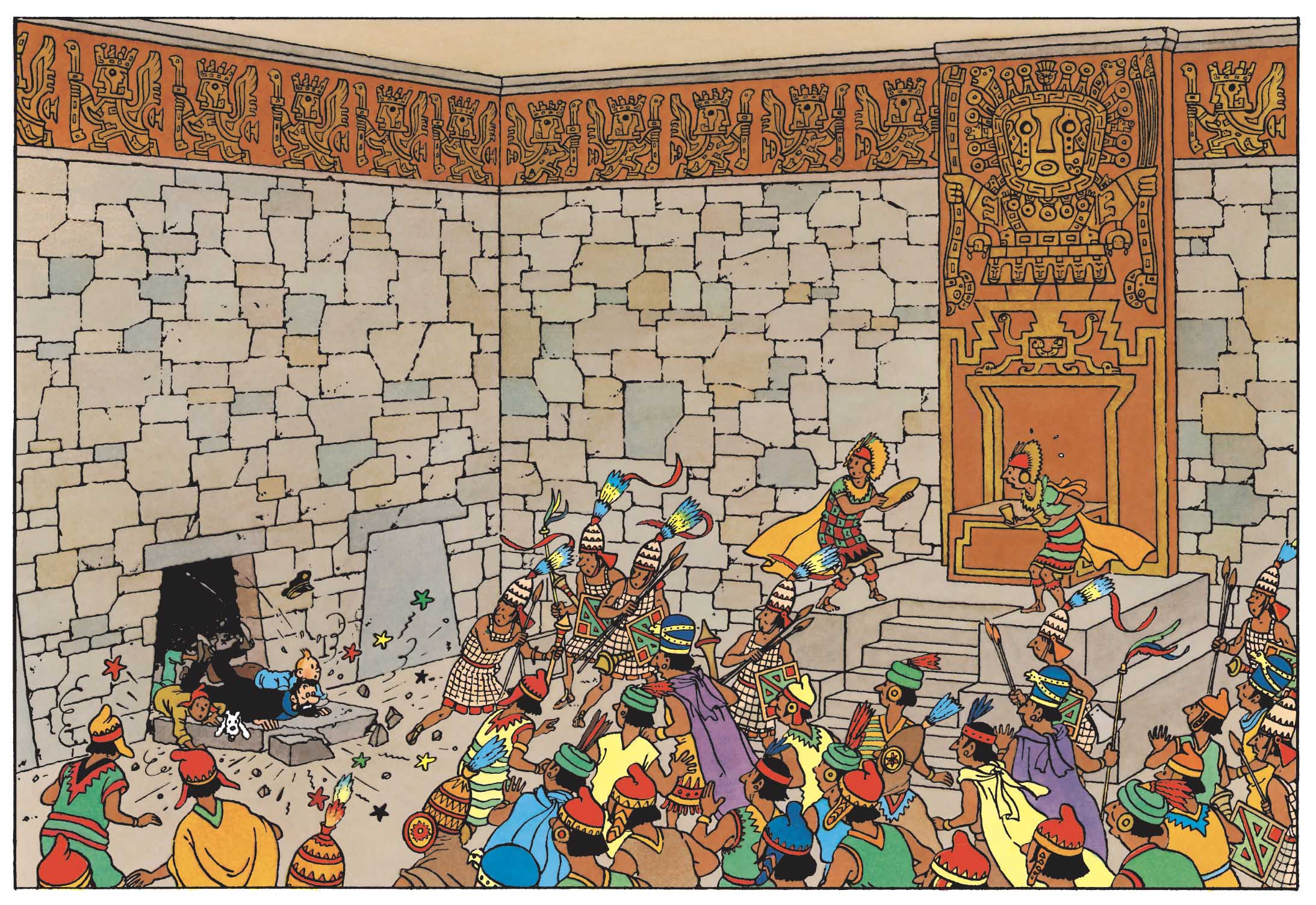

Hergé conceives these spaces as true proving grounds. The mountain isolates, the sea exposes, the city traps, the desert exhausts. And always, these places rest on rigorous documentation, photographs, travel accounts, sketches, before being reworked into immediately recognizable settings. Remove Tintin, and an entire imaginary geography collapses. How could one not marvel, for instance, at the reconstruction work in Prisoners of the Sun? These Épinal-like images, made obvious through repetition, are owed to Tintin as well.

Objects as triggers and repositories of memory

Objects are never neutral in Tintin. Cobbed together or manufactured, canned or plastic, metal or copper, they carry the plot, condense the past and orient the action. The model of the Unicorn in The Secret of the Unicorn, the parchments it conceals, the royal sceptre at the heart of King Ottokar’s Sceptre, the Arumbaya statuette in The Broken Ear, or the cane that holds the secret in The Calculus Affair are far more than mere accessories. They are fragments of history around which everything is organized.

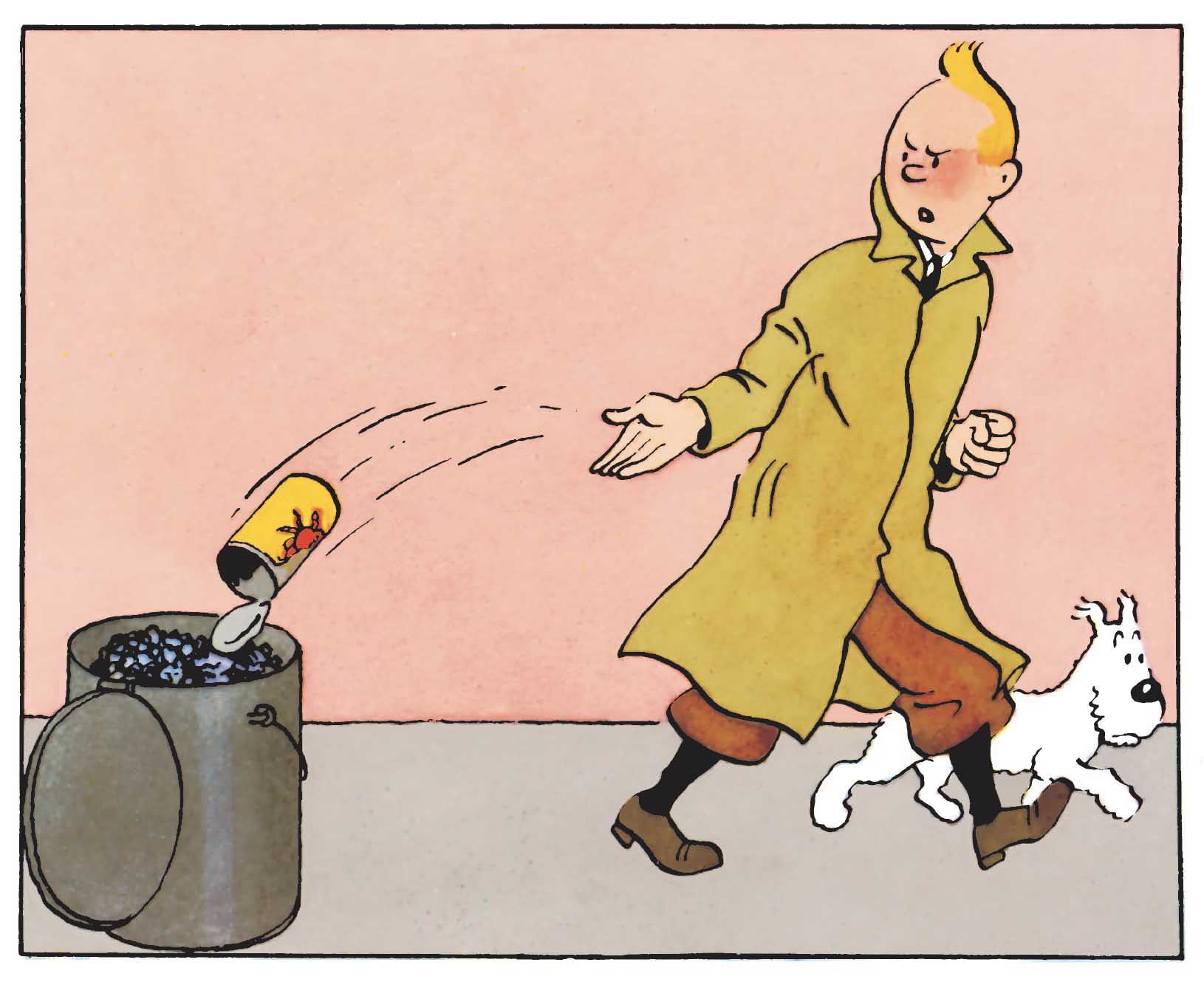

Hergé grants them almost obsessive attention: exact proportions, credible materials, precise uses. Each object becomes a visual and narrative anchor, instantly recognizable. Without them, the adventure would scatter. With them, it gains structure, transmission and memory. And sometimes, everything begins with almost nothing: a simple empty tin can, found by Snowy in a trash bin, is enough to set the entire plot of The Crab with the Golden Claws in motion. Without Tintin, even these modest objects would have remained mute. In his universe, great adventures are often born from details that appear insignificant…

Tintin, reporter-detective

Before acting, Tintin is an investigator at heart, in whom a saving eureka can suddenly emerge. There were reporters before him, of course. But beyond the outcome, much of his investigative work rests on these calm, often overlooked moments when nothing has exploded yet.

In The Secret of the Unicorn, Tintin examines a flea market, compares objects, patiently assembles clues. In The Blue Lotus, he observes attitudes, silences, betraying gestures. In The Castafiore Emerald, he barely runs at all: he listens, doubts, cross-checks, to the point of understanding everything, beyond even the clichés.

These images show a Tintin who is still, bent over, attentive, sometimes relegated to the background of the panel. Hergé constructs a hero who does not always triumph through strength or speed, but through patience and a careful reading of reality. These are less spectacular images, but essential ones. Without them, Tintin would be just another adventurer. With them, he becomes a character who understands before acting, and whose intelligence is first expressed through observation.

Relentlessly, sometimes with difficulty, Hergé built, album after album, a universe of rare coherence, shaped by observation, documentation and an almost obsessive demand for clarity.

By asking what would remain if Tintin had never existed, we measure above all what was patiently constructed: images, characters, places, gestures, a way of storytelling steeped in nostalgia... Tintin was not born of a miracle, but of hard work, repeated, refined, begun again. A universe to reread, again and again, to remember that it owes nothing to chance… and that it very much exists.

Textes et images © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2026

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books