Draw yourself!

It seems that if you want a job done well, do it yourself. Hergé clearly turned this saying into an immutable graphic rule: nobody can draw you better than you can! From there, it's only a short step... or rather, a stroke of the pencil to explaining the profusion of self-portraits and self-caricatures in his work.

After all, self-portraits are nothing new. The practice dates back to the early Renaissance, when artists began to depict themselves in their own paintings – not out of vanity or for anecdotal reasons, but to gain recognition. By portraying themselves in historical and biblical scenes (often relegated to the background and/or the edge of the painting), they were silently asserting... that we exist too.

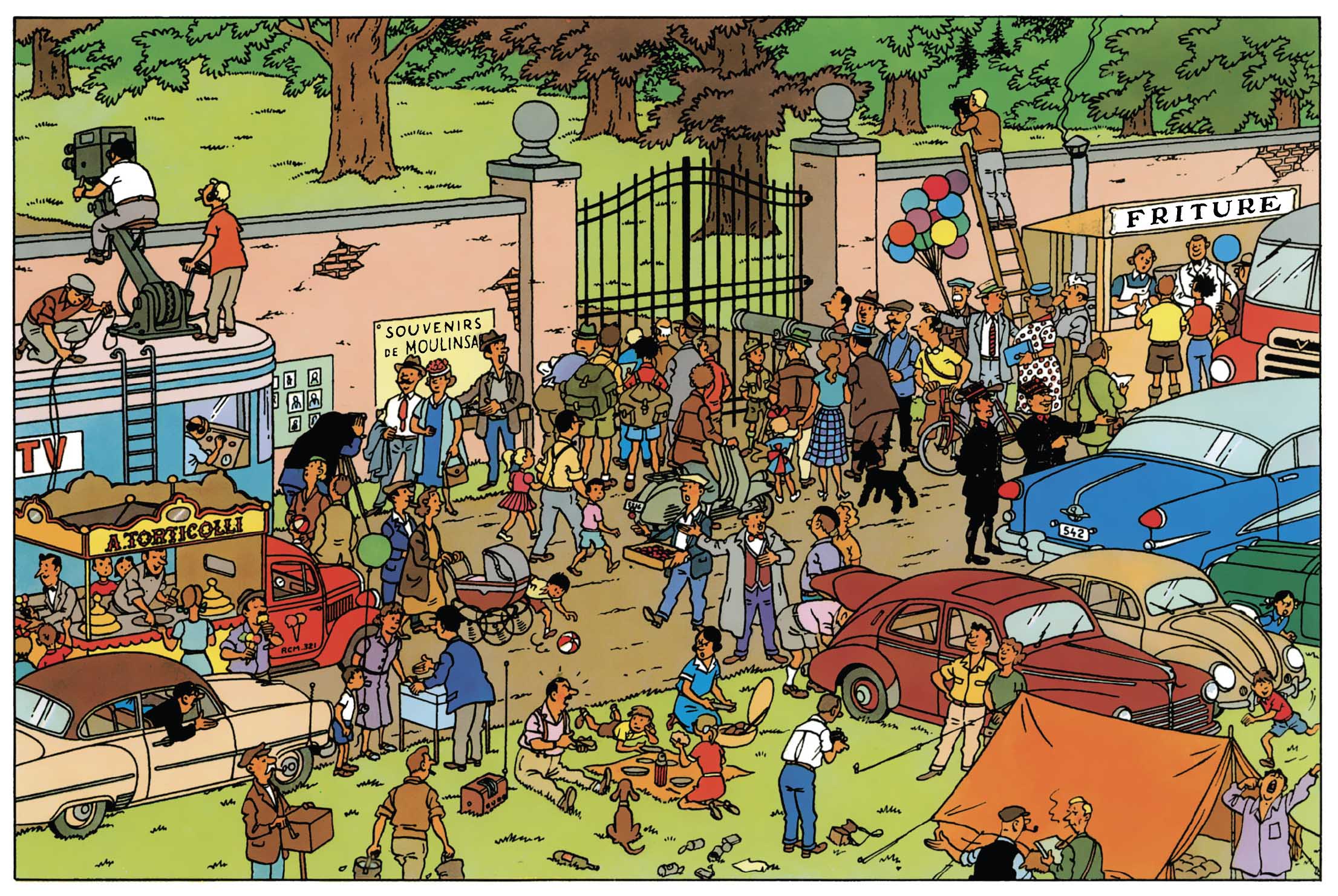

With Hergé, of course, the approach is quite different. Social recognition is no longer an issue because, in the meantime, the artist has become an indispensable cog in the wheel, especially when he puts his talents to work in print. However, the Belgian cartoonist learned a valuable lesson from the masters of the Quattrocento: that of self-representation in assistenza, or ‘among the crowd’

.

Where is Hergé?

In The Adventures of Tintin, Hergé makes a habit of discreetly slipping in among the onlookers, like Alfred Hitchcock playing an extra in his own films. It is certainly a trademark, but above all a subtle way of connecting with his readers.

In almost every adventure, he sets them an implicit challenge – Can you find me? This was long before Martin Handford popularised the concept with his famous series of Where's Wally books?

Hidden somewhere among the crowd, Hergé watches the scene unfold. And if you're having trouble spotting him, don't panic, here's a valuable clue to help you: he usually depicts himself with a sketchbook and pencil in hand, as if to remind us that, even in fiction, he is a hard worker. Now that you know this... can you find him in this well-known vignette from The Calculus Affair?

Incriminating portraits

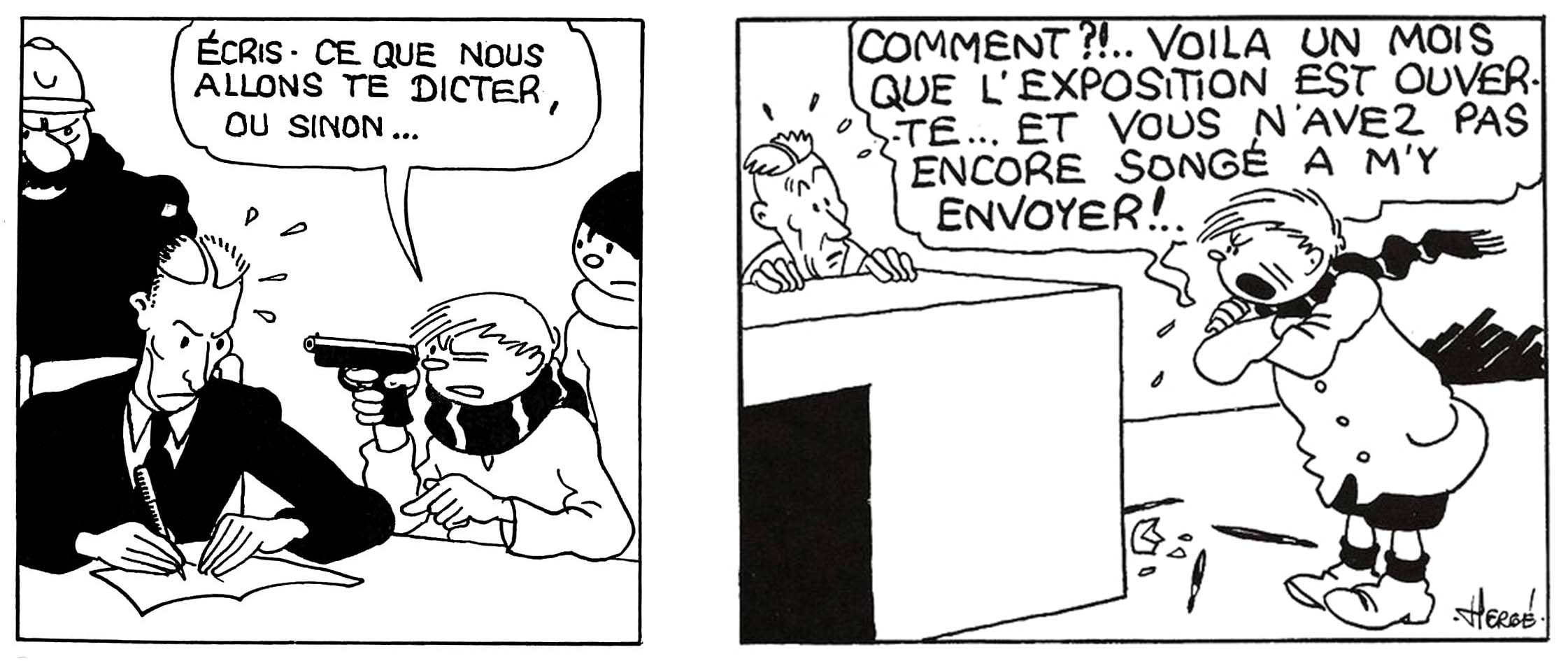

But self-portraits in Hergé's work are not just a graphic gimmick. Initially, they were a comic device, a means of expressing humour and self-mockery – two qualities that are, as we know, deeply ingrained in the Belgian DNA.

It is therefore not surprising that, in Quick and Flupke, he plays the role of the whipping boy, taking threats, blows and other reprimands from his rowdy Brussels kids without complaint, to amuse the audience a little more. By laughing at himself in this way, he never places himself above his characters. Better still, he clearly shows that he is one of them!

Left hand vignette text: WRITE DOWN WHAT WE ARE GOING TO DICTATE TO YOU. OR ELSE… Right hand vignette text: HOW COME?!..THE EXHIBITION HAS BEEN OPEN FOR A MONTH NOW... AND YOU HAVEN'T EVEN THOUGHT OF SENDING ME THERE YET!..

Narratively speaking, the caricatured portrayal of himself allows him to cleverly break a fourth wall of a special kind: not the one separating the protagonists from the reader, but the one separating them from their own creator. This technique obviously adds an extra dose of humour and complicity to this already colourful universe.

Vignette text: HOW COME?.. YOU HAVE A WHOLE PAGE IN WHICH TO MANOEUVRE ME AND YOU STILL HAVE TO THROW ME AGAINST THE FRAME OF THE DRAWING!!...

Humour always

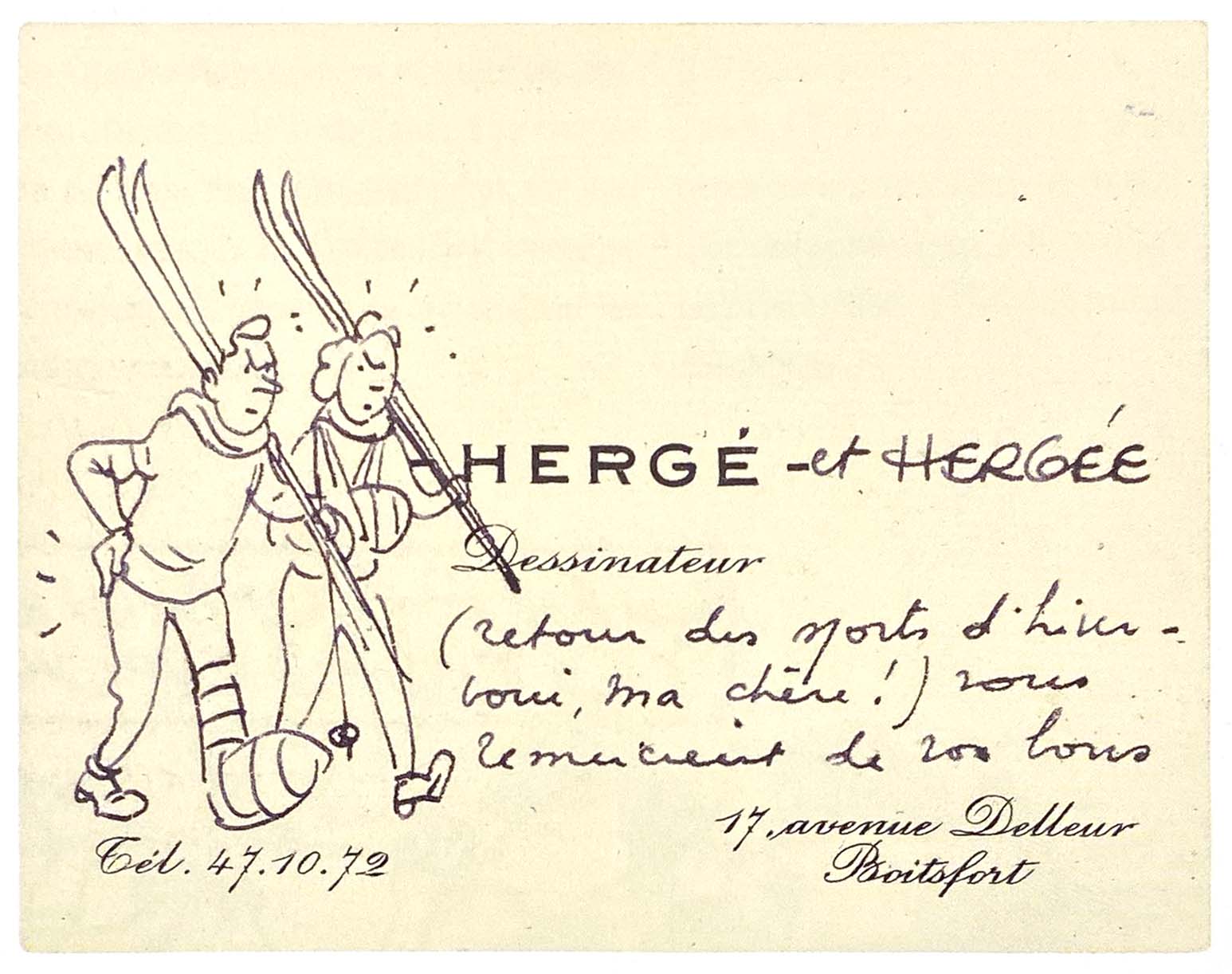

This vein of self-mockery also runs through his correspondence – particularly the illustrated postcards, greeting cards and business cards he liked to send to his friends and family. But this time, he portrays himself, without mercy, as the victim of his own personal “exploits” – whether they be winter sports mishaps or other everyday setbacks.

The whole story is told in just a few strokes and words, of course, but with a keen sense of humour. These miniature sketches show how much the little annoyances of life amused and inspired him, as he immediately transformed them into comic material.

Text of the business card: Hergé and Hergée (back from winter sports, here I am!) thank you for your kind

wishes.

And if there were still any doubt about the essential role of self-mockery in his work, one need only refer to page 5 of Tintin magazine No. 51 from December 1962. There we find a delightfully dark self-portrait of him, depicted with the lights off, lost in the middle of a vignette logically bathed in... black humour! A graphic pirouette as concise as it is effective, showing just how much he knew how to laugh at himself, even in the darkest situations.

Vignette translation: OH NO! MY LAMP HAS JUST GONE OUT!

To find out more about this subject, please see Mag Tintino No. 9 entitled ‘Moi, Hergé’ (Me, Hergé).

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2026

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books