Disguises and subterfuges

Carnival season is in full swing across Europe, filling the streets with masks and costumes. What better time to focus on an unexpected master of disguise: Tintin. Though rare, his clever disguises reveal his knack for subterfuge, turning deception into a true art of adventure.

Throughout his journeys, Tintin often has to improvise as a master of disguise to escape tricky situations. Whether facing unexpected adversaries or blending into unfamiliar environments, these transformations - sometimes surprising, sometimes comical - demonstrate his ingenuity and adaptability. Like a chameleon, what roles has he taken on across the albums? And what do these transformations reveal about the cultures he encounters? Let’s delve into this fascinating and often-overlooked aspect of Hergé’s work.

Traveling across the world, whether as an adventurer or an investigator, Tintin’s costume changes are never arbitrary. They serve the narrative, heighten suspense, and occasionally add a sharp touch of humor.

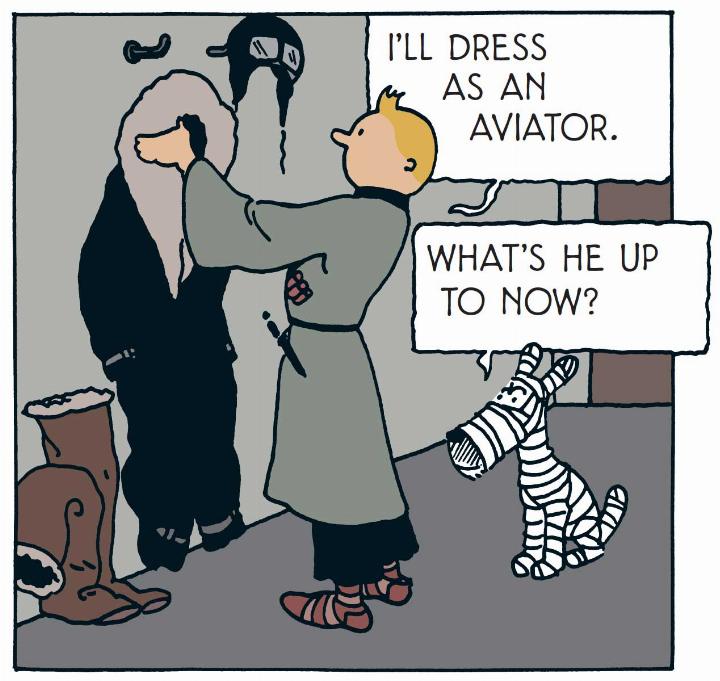

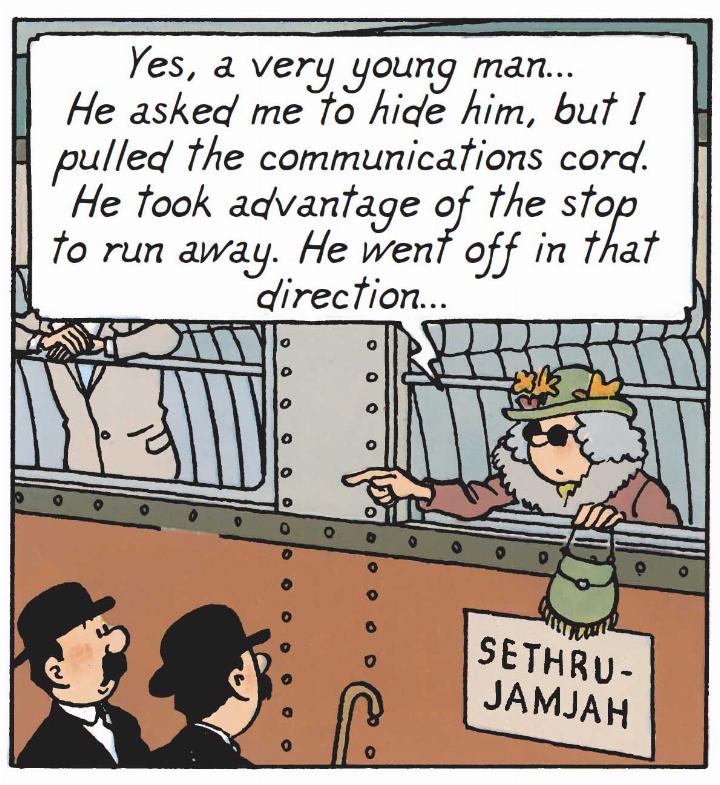

"Yes, a very young man… He asked me to hide him, but I pulled the alarm. Only, he took advantage of the stop to escape. He went in that direction.". Once again, the ever-gullible detectives Thomson and Thompson are fooled. Disguised as a woman, Tintin skillfully outwits his pursuers in the intricate plots surrounding the Maharaja and his son. But no matter the peril, Tintin always lands on his feet - even in a dress! After all, a good reporter must know how to blend in, even if it means trading his signature plus-fours for something a little less expected.

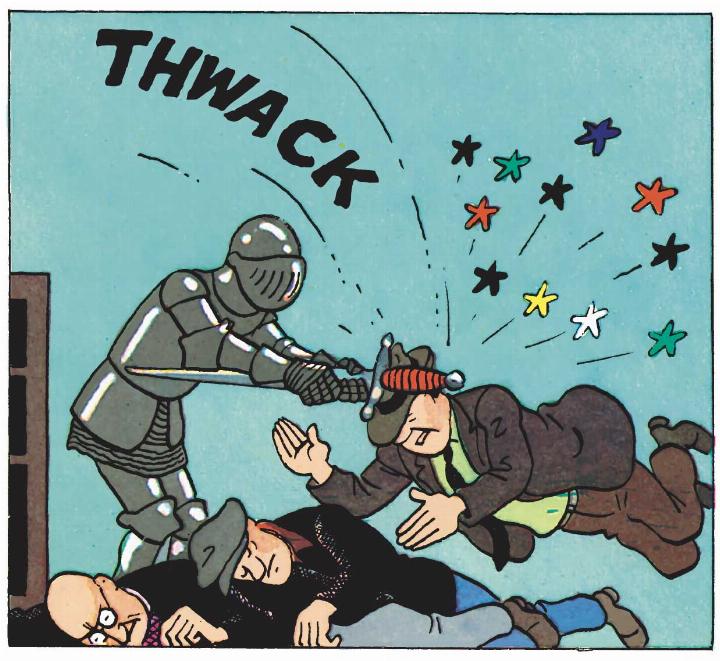

Facing a gang of kidnappers in their fortress along the Silvermount route in Tintin in America, Tintin hesitates briefly before settling on an unusual strategy - donning a full suit of medieval armor. The heavy metal suit, roughly resembling plate armor from the late Middle Ages, adds a comical touch as Tintin, clanking from head to toe, manages to knock out his enemies in an almost slapstick fashion. Long associated with European medievalism, these cumbersome suits of armor remain embedded in collective imagination, often found in museums or repurposed castle décor, even though their true golden age was during the early Renaissance.

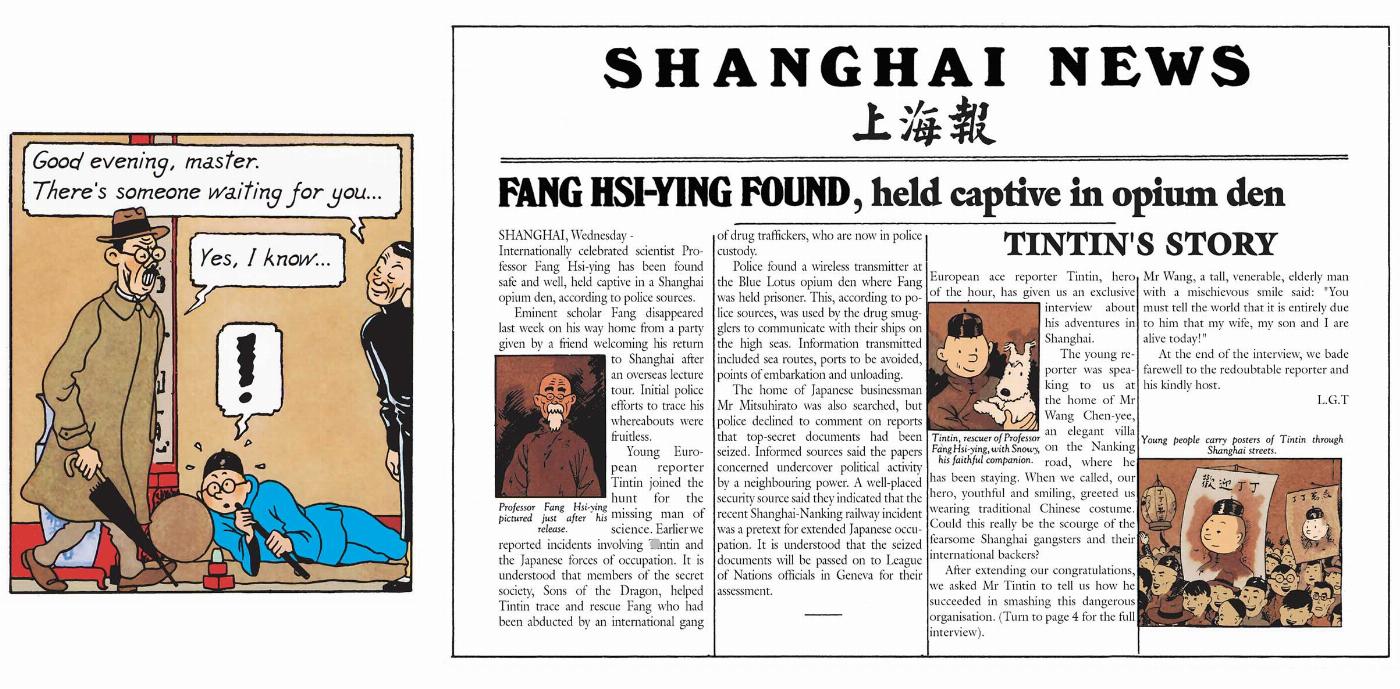

When adapting to unfamiliar terrain, Tintin relies on quick thinking and keen observation, often acquiring or repurposing clothing to deceive his determined foes. As mentioned in our recent dossier Nights in China, the young reporter dons a traditional Chinese robe, later described in a Shanghai newspaper article as "wearing traditional Chinese costume".

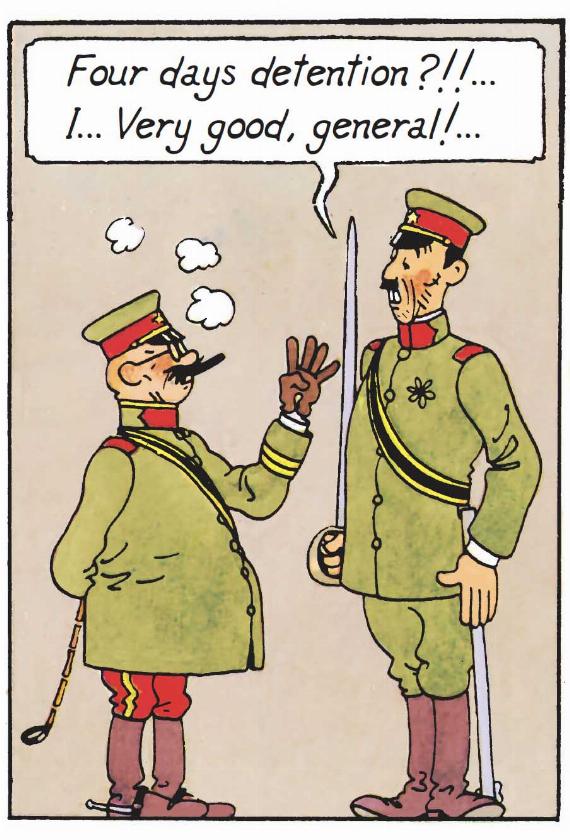

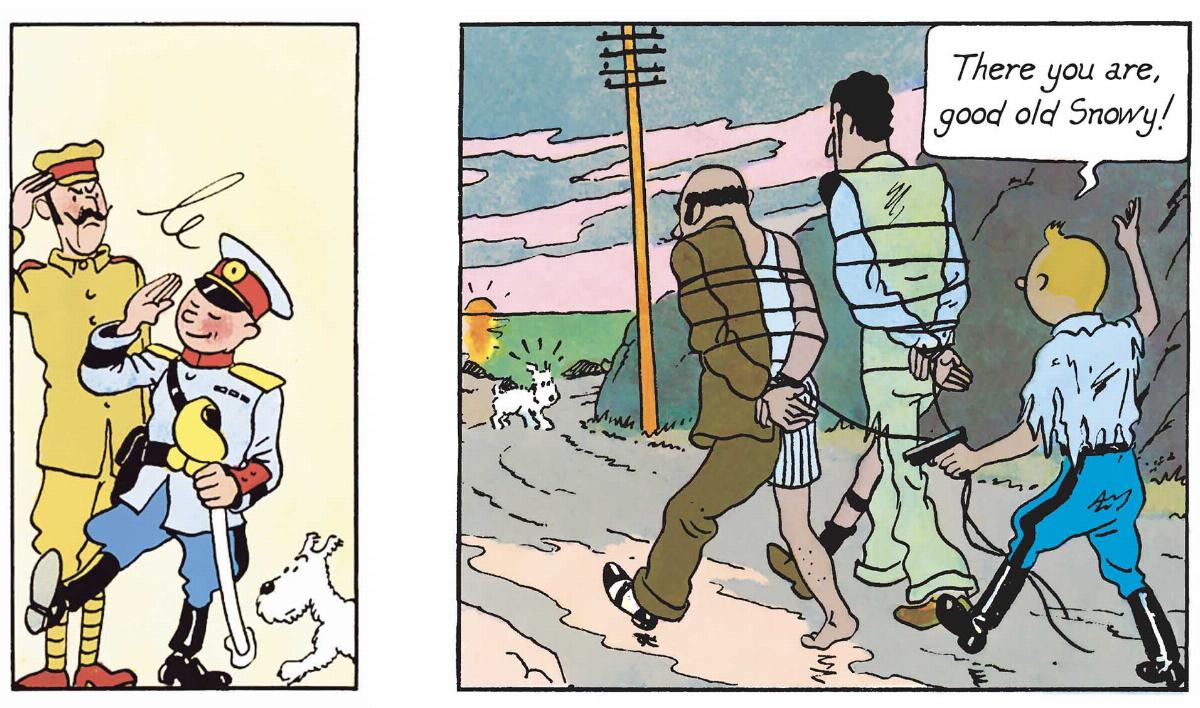

In the same album, Hergé playfully mocks the rigid discipline of Japanese officers and soldiers: disguised as a general, Tintin hides Snowy beneath his jacket, using his suspenders to create the illusion of a portly figure. Without speaking a word of Japanese, he simply raises four fingers - prompting the baffled officers to assume he is sentencing them to four days’ detention for trivial infractions. Once again, the clothes make the man.

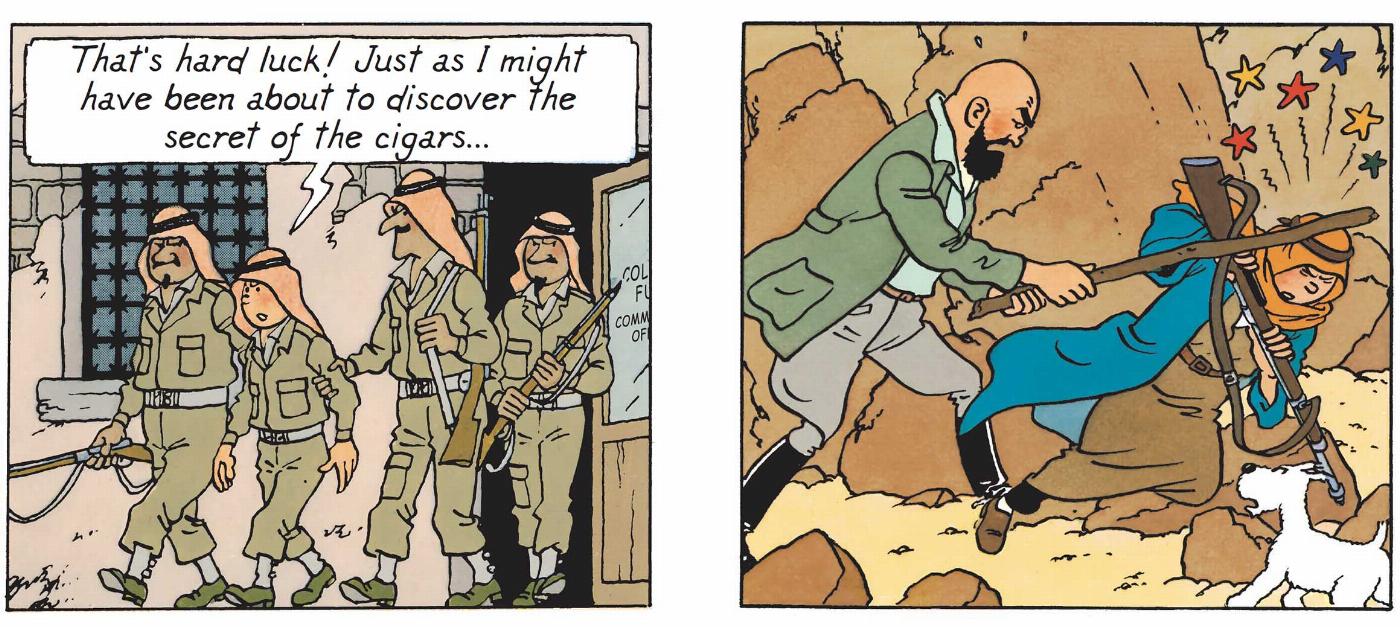

In Cigars of the Pharaoh, while infiltrating an international drug cartel, Tintin wears the ominous purple robe marked with the royal Kih-Oskh symbol. With a good dose of luck, he manages to take down most members of the sinister opium-smuggling cult - except for the ever-elusive fakir, who narrowly escapes.

Packed with absurd situations, this adventure also sees Tintin mistakenly enlisted in military training, where he is assigned the alias “Beh-Behr” and subjected to grueling drills before being caught in the act. Whether in rags, a Bedouin tunic in Land of Black Gold, or various disguises, Tintin’s outfits are not always foolproof, but they certainly reflect an orientalist fascination that is part of his storytelling legacy.

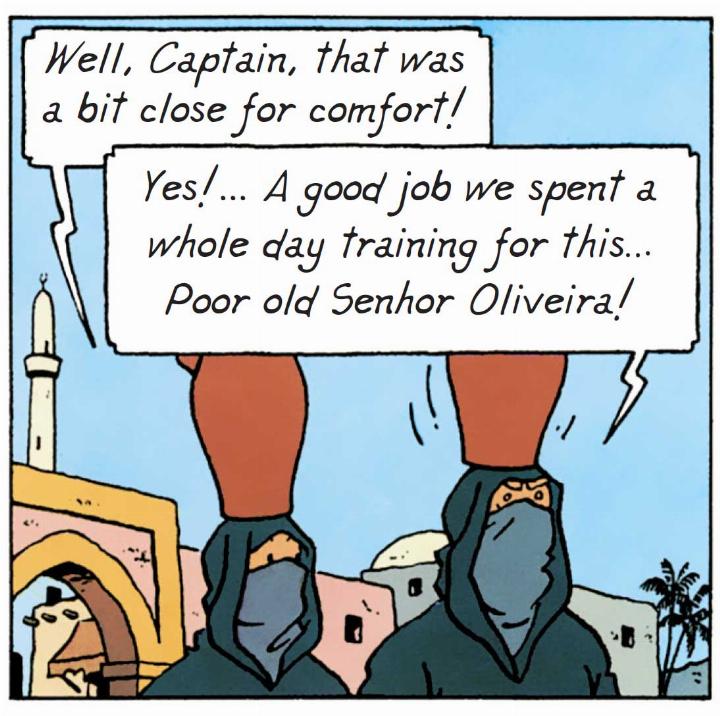

On the way to Khemed, an imaginary oil-rich monarchy near the Red Sea, Tintin and Captain Haddock face numerous obstacles but still find time to disguise themselves as water carriers, draped in full-body black veils. Water on Haddock’s head? What a dreadful idea!

Another whimsical disguise: caught up in a state conspiracy in The Broken Ear and miraculously surviving three execution attempts, Tintin is abruptly recruited by General Alcazar and promoted to the rank of colonel. With no other choice, he dons the sky-blue uniform. His stylish attire, however, doesn’t stay pristine for long - by the time he escapes his pursuers, it’s little more than a collection of rags.

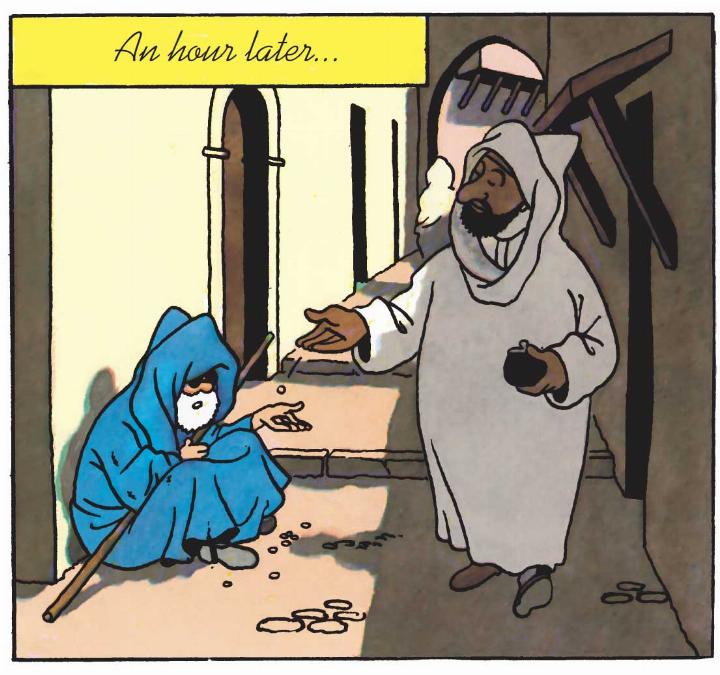

In The Crab with the Golden Claws, Tintin disguises himself as a beggar, blending into the city streets to investigate a smuggling network tied to the mysterious crab tins from the Karaboudjan. His deception leads to a chaotic yet hilarious scene where Captain Haddock, in a drunken stupor, belts out a song while thrashing his captors. This disguise is particularly telling, as it shows Tintin using ordinary roles to remain unnoticed while still driving the action - despite appearing far from the fearless reporter we know.

Finally, in Tintin and the Picaros, Hergé fully embraces theatricality, dressing Tintin and Haddock in fictional carnival costumes. Their disguises as members of the « Joyeux Turlurons » - a made-up folk group - seem to reference various Belgian carnival traditions, such as the Blancs Moussis of Stavelot, the Chinels of Fosses-la-Ville, and possibly even the famous Gilles de Binche.

Tintin's disguises reveal much about the evolution of his character and his relationship with the cultures he encounters. First and foremost, these transformations showcase a Tintin who, far from being a mere amateur adventurer, demonstrates remarkable adaptability. Although Hergé himself traveled far less than his hero, he crafted thrilling and entertaining adventures that transported his readers across the globe.

Within this framework, Tintin serves as a window into rich cultural settings, allowing readers to explore worlds different from their own. Through imaginative costumes, he embraces recurring historical themes - such as the Opium Wars, the curse of Tutankhamun, and the carnivals of Western Europe and Central America - while incorporating strong visual references, such as the emblem of Kih-Oskh, which embodies both the Yin-Yang symbol, or taijitu, and various other influences that continue to spark lively debate among Tintin enthusiasts.

In every example cited, Tintin strives to blend into unfamiliar environments, immersing himself in local cultures while sparking moments of humor and misunderstanding. Yet behind the mask, he remains the same intrepid reporter - always investigating, uncovering, and untangling the mysteries of a fascinating world that never ceases to inspire our imagination.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books