When Calculus shook Europe

Attention, we’re being bugged! The walls have ears, even at Marlinspike Hall...

In The Calculus Affair, Hergé no longer takes us through the mysteries of lost civilizations. We’re no longer in Inca temples or oriental deserts, magnificently reimagined through the documentation of his time, but in the heart of post-war Europe, a rational and uneasy world where science has replaced mystery. A science that now arouses fear as much as curiosity.

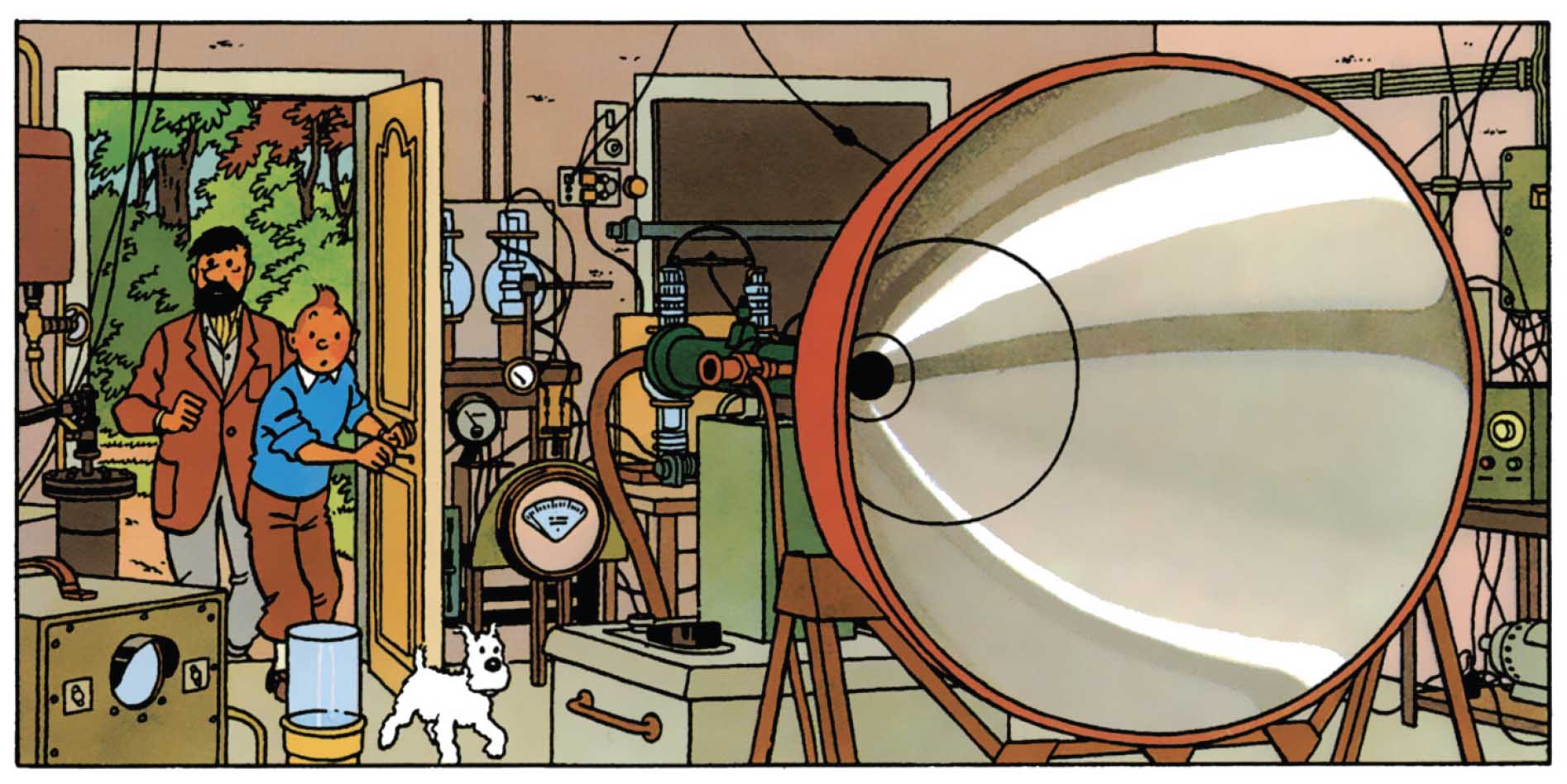

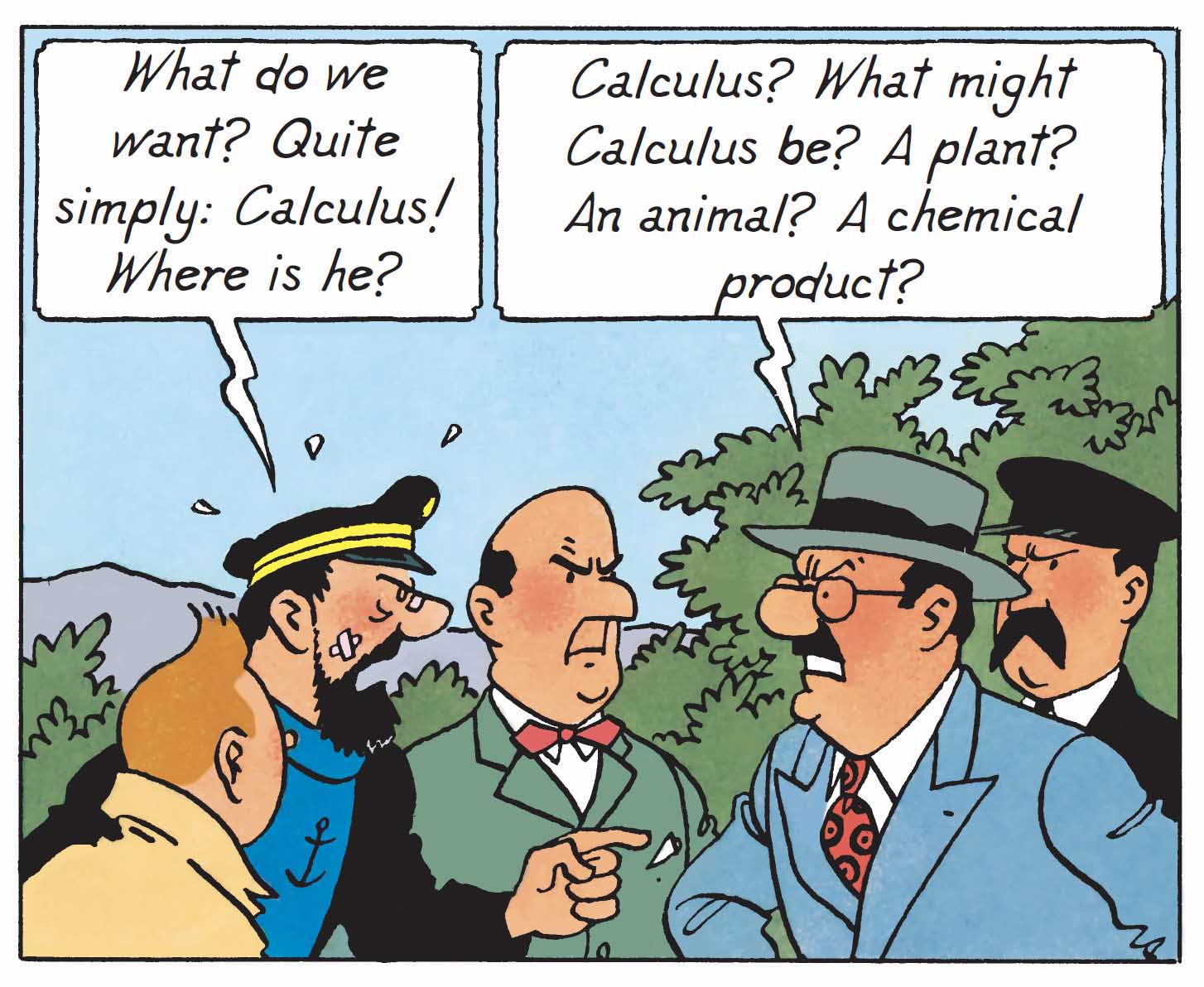

Professor Calculus, until then a whimsical inventor, becomes the center of a new kind of tension. His laboratory at Marlinspike turns into a powder keg. His invention, a device capable of focusing ultrasounds to the point of shattering glass and metal, arouses every kind of covetousness. And to top it off, the odd bird has vanished…

The idea was born from an anecdote, trivial but real, reported in a Belgian newspaper: on an English road, car windshields were mysteriously shattering without reason. Hergé saw in it a point of departure, a sign of the times. Technical progress, invisible and triumphant, was beginning to worry people. « I looked around me. International conflicts, travel, scientific inventions, current events are an inexhaustible source, » Hergé told one of his readers. It was 1954, in the middle of the Cold War. The atmosphere was tense, laboratories were full of shadows, and science was becoming a double-edged weapon.

To give substance to this idea, Hergé documented himself with almost obsessive care. In his notebooks appear photographs of parabolic sound mirrors built in Germany during the war, designed to concentrate sound into deadly beams. There we find the name of an American engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Earl Simon, author of a technical study on acoustic research carried out under the Speer Ministry. Hergé borrowed from these images the form of the instrument that Calculus proudly brandishes before becoming its prisoner. It’s no longer an artist’s fancy, it’s a plausible hypothesis, an invention that reality could almost claim as its own.

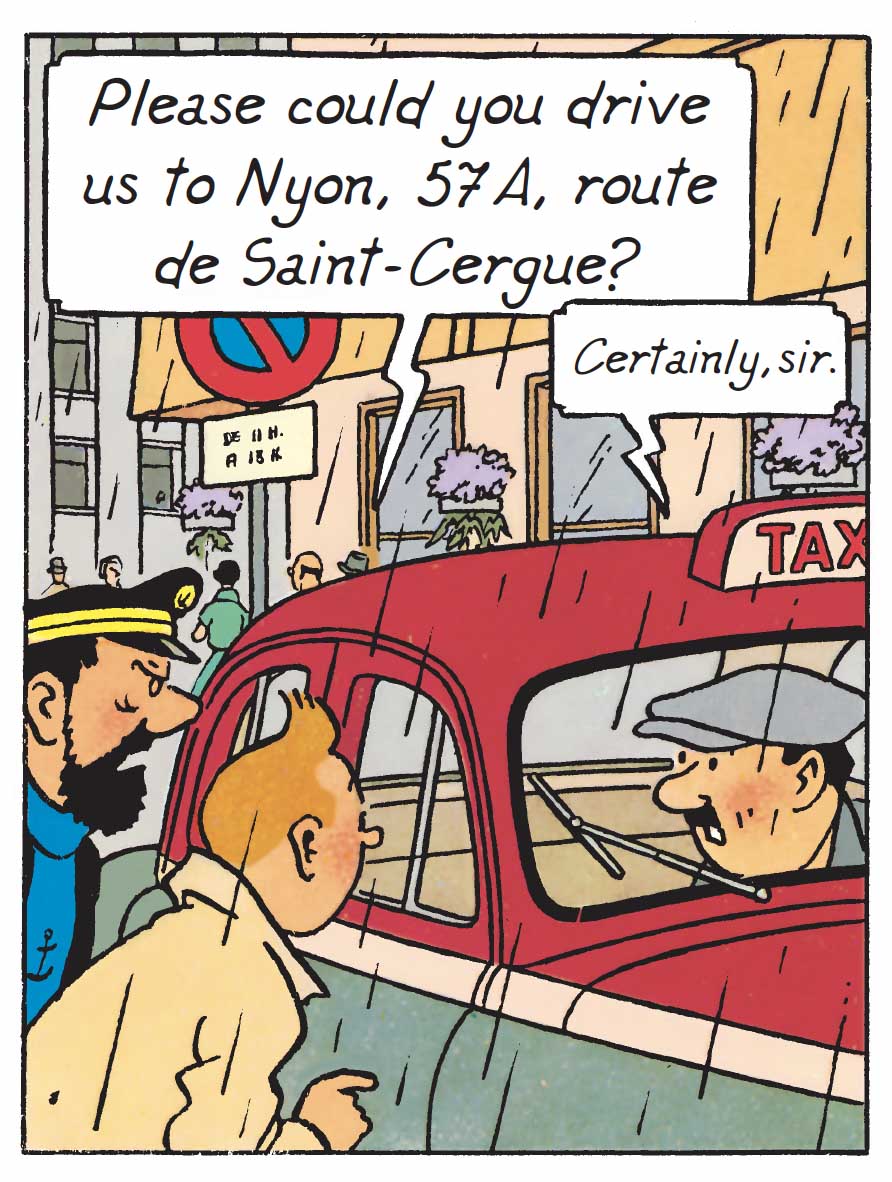

Around this idea, everything fell into place. Within the framework of his album, set in Geneva, Hergé sent his collaborators on location around Lake Geneva. The façades, roads, and landscapes of Switzerland reappear in the panels with meticulous realism. The adventure ceases to be an exotic chase and becomes a European investigation, halfway between a spy novel and a scientific chronicle. The letters exchanged with Casterman bear witness to his demand for precision. Every building, every vehicle, every laboratory light had to feel authentic. Hergé’s meticulousness is legendary, just look at those daring double-page spreads!

But for Hergé, precision was never just a matter of setting; it became a language. All that realism, all that detail, served not to make things « true », but to make them felt. In this album, science and secrecy blend together. Calculus, once a kindly and absent-minded scholar, takes on a new dimension. He becomes the symbol of a time when invention carries responsibility. Yet his machine immediately attracts the attention of spies, and before long, he finds himself caught in their web!

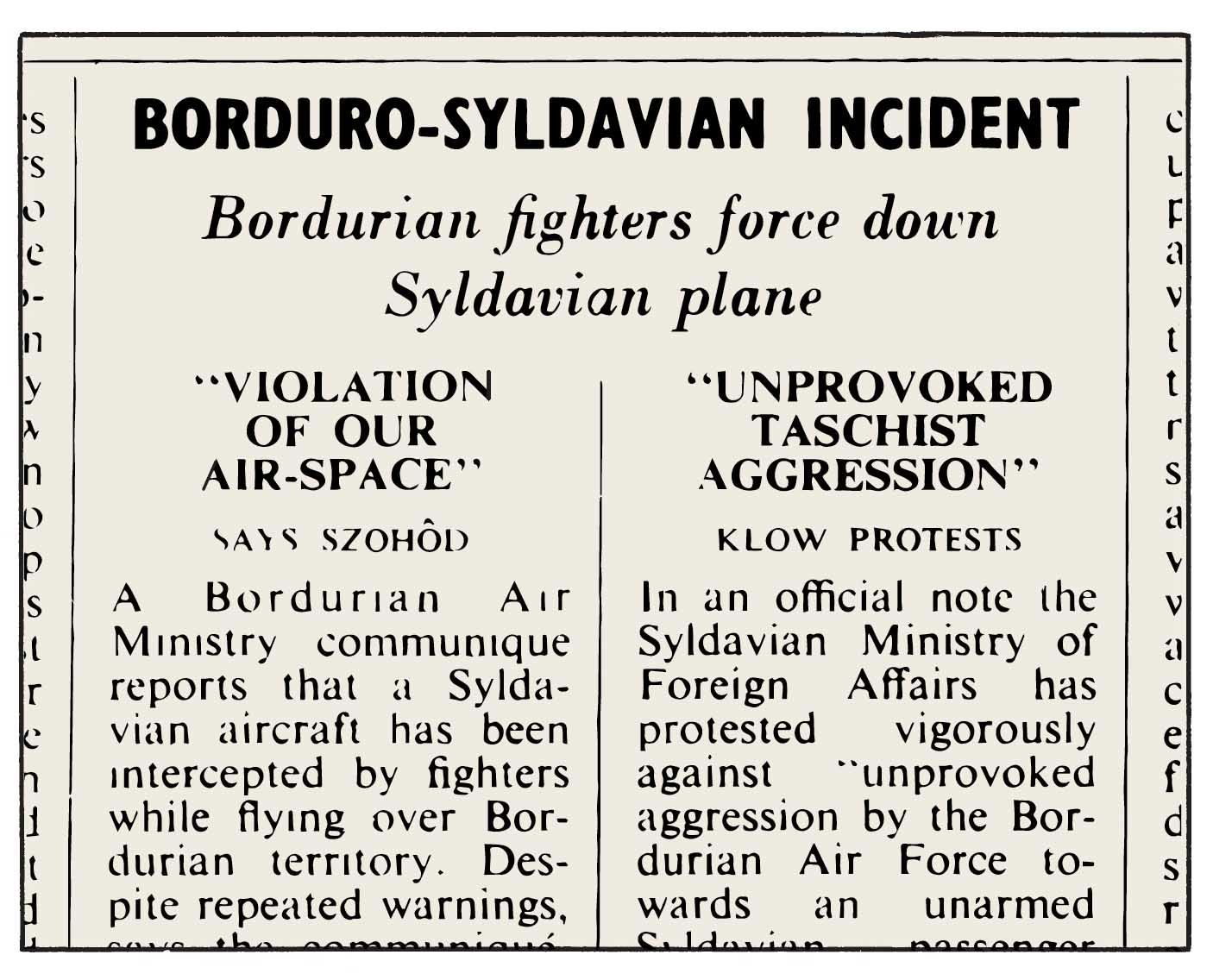

Hergé’s choice to set the story in the middle of Europe was no accident. He was observing a world where opposing blocs fought in other ways: through science, intelligence, and invention. The United States and the USSR competed to recruit German scientists (von Braun, Einstein, and so many others) as if they were living weapons. The Calculus Affair transposes that reality without ever naming it. Syldavia and Borduria stand in for these nameless powers, each trying to seize knowledge it cannot fully master.

Ever concerned with credibility, Hergé chose to make Calculus’s device operate on high frequencies (between 16 and 1,000 kilohertz) the range that was said to be capable of shattering glass or distorting metal. This detail, supported by technical documentation, anchors the fiction firmly in reality. The reader no longer doubts it: this machine could exist. Between this invention and the famous Tryphonar, the boundary between science and imagination becomes almost invisible.

Around him, Hergé relied on a tightly knit team. Jacobs, Bob de Moor, and Jacques Martin all contributed to the technical designs, machines, façades, laboratory furniture. Together, they aimed for a visual truth that borders on the photographic. These location studies, carried out around Lake Geneva and supported by meticulous exchanges with Casterman, give the album a near-journalistic grounding.

And yet, despite all this realism, a strange tension lingers. Glass shatters, windows vibrate, rain drums on façades. The danger is never seen, but always felt. And yes, there’s glass breaking, a Jolyon Wagg driving Captain Haddock mad, and those Bordurian faces we can’t help but laugh at. And as always, Calculus doesn’t quite understand what’s going on, but he keeps going, his trusty umbrella in one hand, a brilliant idea in the other. Why is that umbrella so important? You’ll have to read the album again to find out.

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2025

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books