Tintin at the table

Winter is back, and so are the end-of-year celebrations. Which means it's time to get down to the business of preparing festive meals. If you're short of ideas, don't panic: Hergé and his gastronome in Plus Fours, have something to inspire you with a selection of culinary sequences of their own.

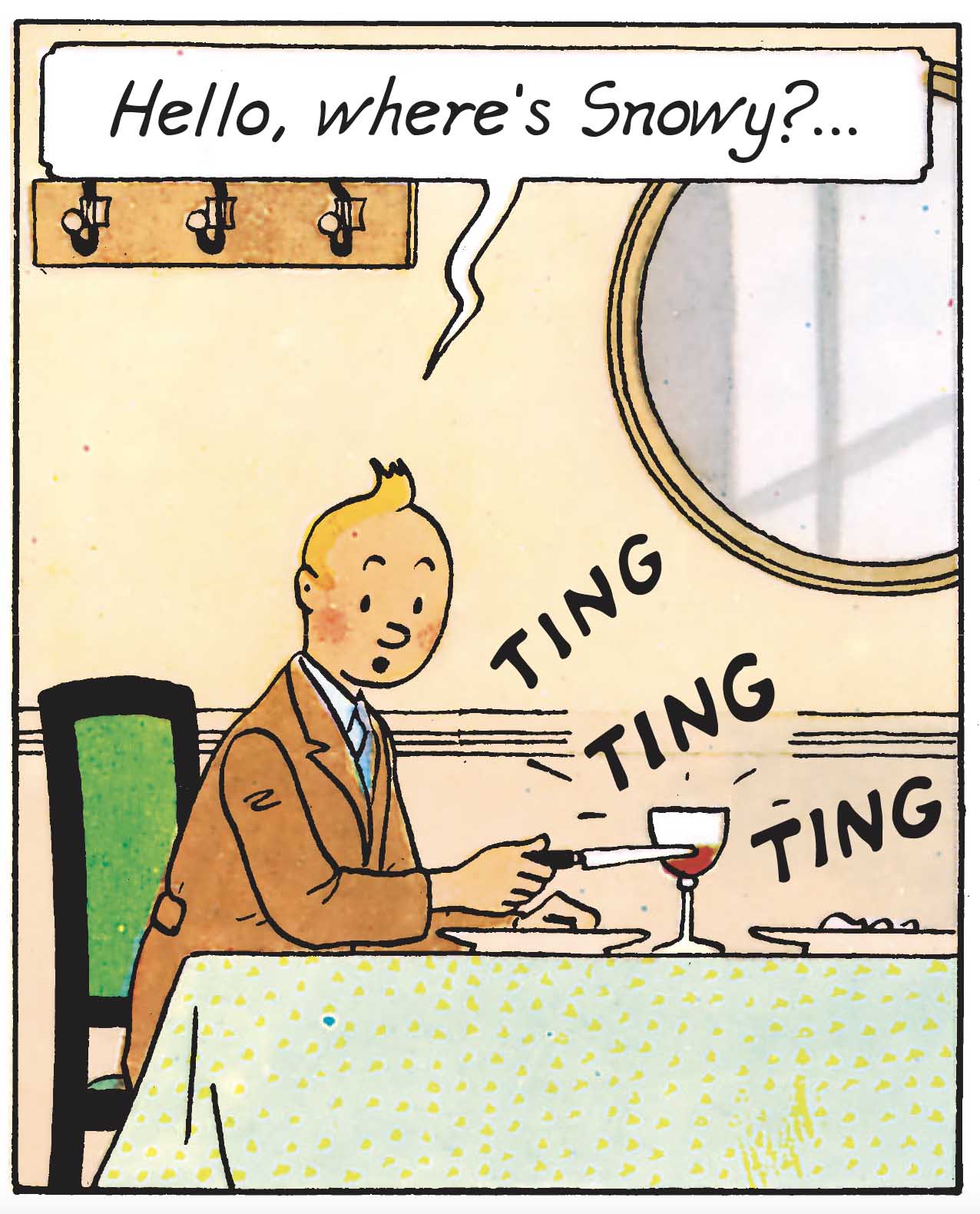

The table is set... A delicious aroma wafts through the air... All that's left to do is wait for the guests to savour the delicious dishes and share a warm moment of conviviality. For it's a fact that, in most of his adventures, the young reporter has made a habit of sitting down to dinner.

The hunger justifies the means

It's surprising, though, because, like any drawn creature, he has no body. In fact, he doesn’t depend on food to live. His existence depends on a single thread: the pencil stroke of his creator.

So eating is clearly not a necessity for him. Yet this activity is no less important. His hunger may not be real, it is on the other hand, very fictional. His meals are, in fact, moments of singular narration. And they're much more powerful than they appear, since they're always the occasion for something of great interest.

On the menu for this "fictional hunger" are recipes of various kinds, to satisfy the appetites of all gourmets, but above all, to keep the story full of twists and turns.

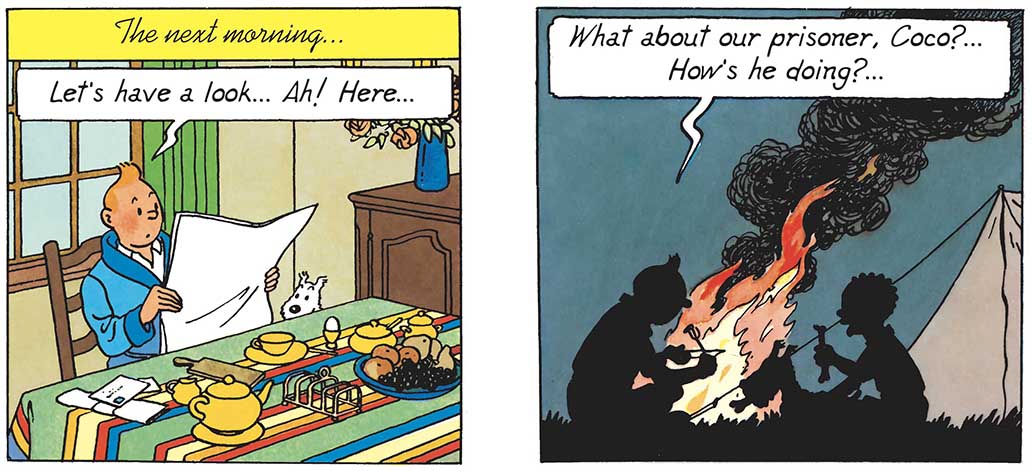

In Hergé's work, meals are a simple and effective indicator of time, since, depending on the type eaten, they implicitly indicate to readers the precise time of day during which the sequence takes place.

Following - as it were - the rules of chrono-nutrition, he also assigns each story a logical and balanced narrative intake. So, at breakfast, he serves his heroes - preferably on a silver platter - new discoveries to get their investigation and their day off to a good start; before offering them a rather hearty, full-bodied "main course" for lunch. And finally, dinner... a final banquet to celebrate victories and progress.

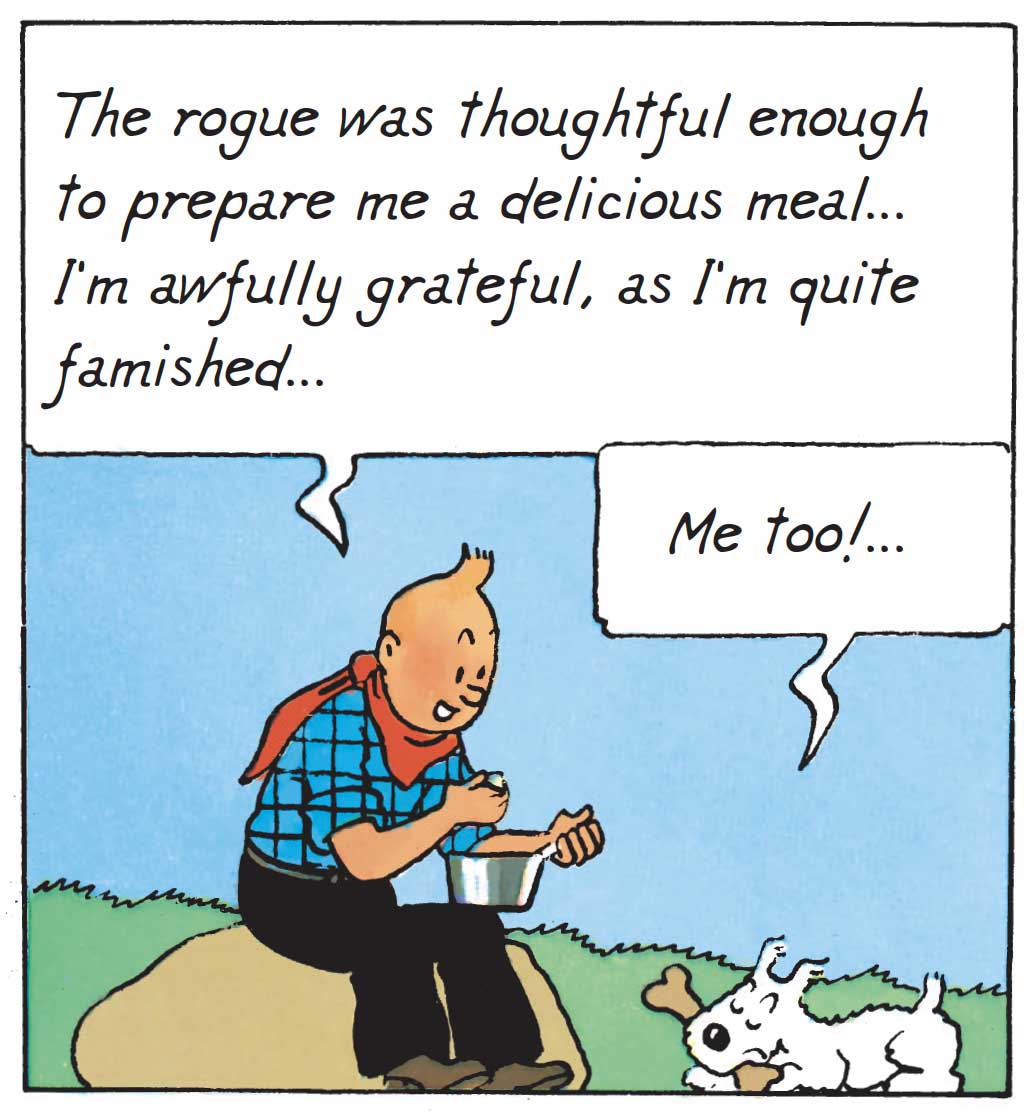

During the effort, comes comfort! This could be the motto of Tintin, who, in the midst of gunfire, doesn't hesitate to take a break... for lunch. It's true that, if the opportunity arises, he'll gladly stop for a bite to eat. This is the case, for example, on his American adventures. This quick meal creates an effective and humorous surprise effect.

In King Ottokar's Sceptre, Hergé once again uses this "stop and go" mode to energise the narrative. But this time, the intrepid reporter doesn't have to stop, as the food literally falls into his arms, as if from the sky. After a brief moment of astonishment, he's off again, enjoying this providential food.

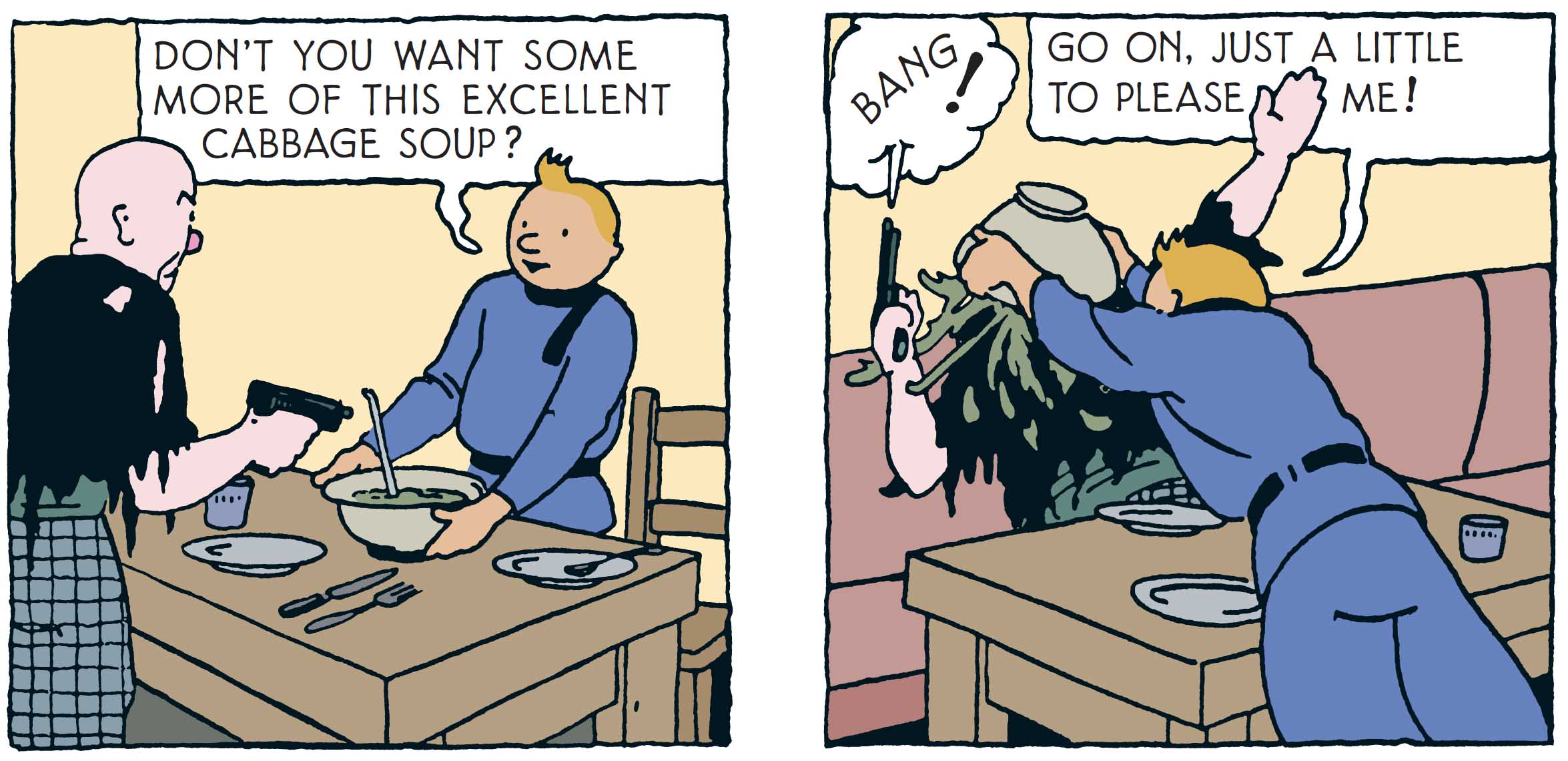

Unfortunately for Tintin, meals are never free. In fact, he often pays a high price for them. And if the bill is high, it's because some ill-intentioned people often invite themselves to his table without warning. When this happens, the meal immediately turns into a trap. Quick-witted and always on the alert, the little reporter quickly senses the trickery and is quick to get rid of these bad payers, even if it means sacrificing a good soviet-style cabbage soup.

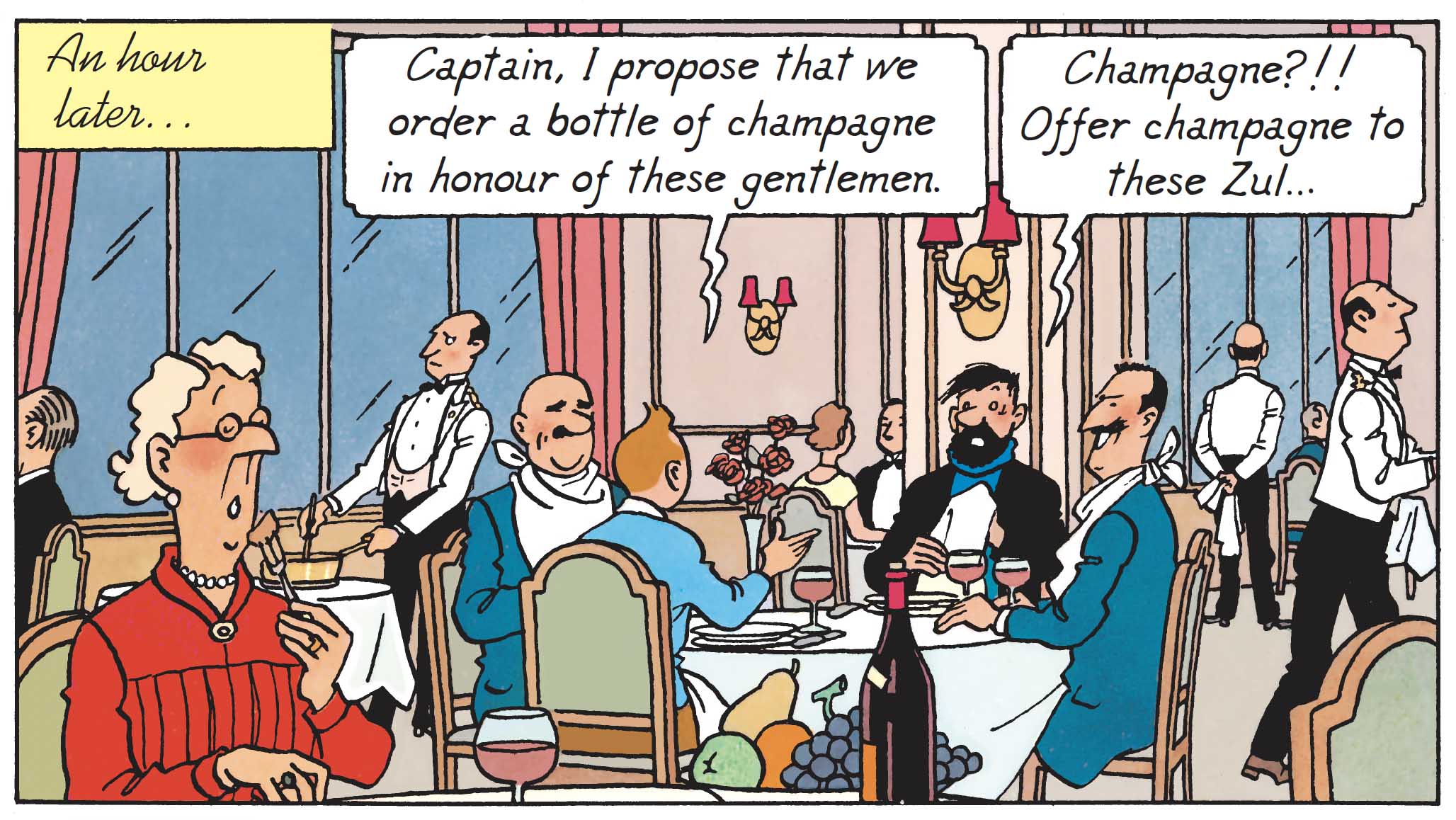

And because the revenge is a dish best served cold, in The Calculus Affair, it's his turn to deceive the enemy. And there's nothing like a good glass of champagne to make him dizzy and loosen his tongue. After all, isn't it customary to say... in vino veritas?

Meals and parties

When it comes to gastronomy, Tintin is having fun throughout his adventures. Depending on the circumstances and/or the place on the globe where he finds himself, the young man is lucky enough to be able to experiment with all sorts of preparations and ways of eating them. It's an opportunity for readers to take a trip down memory lane and discover the extraordinary diversity of the world's cuisines.

Tintin understands: in Rome, it's better to do as the Romans do. There's no better way to learn about the traditions of the people he meets, and to fully immerse himself in their culture. In fact, in China, he is happy to share his table with a stranger, as is customary in popular restaurants.

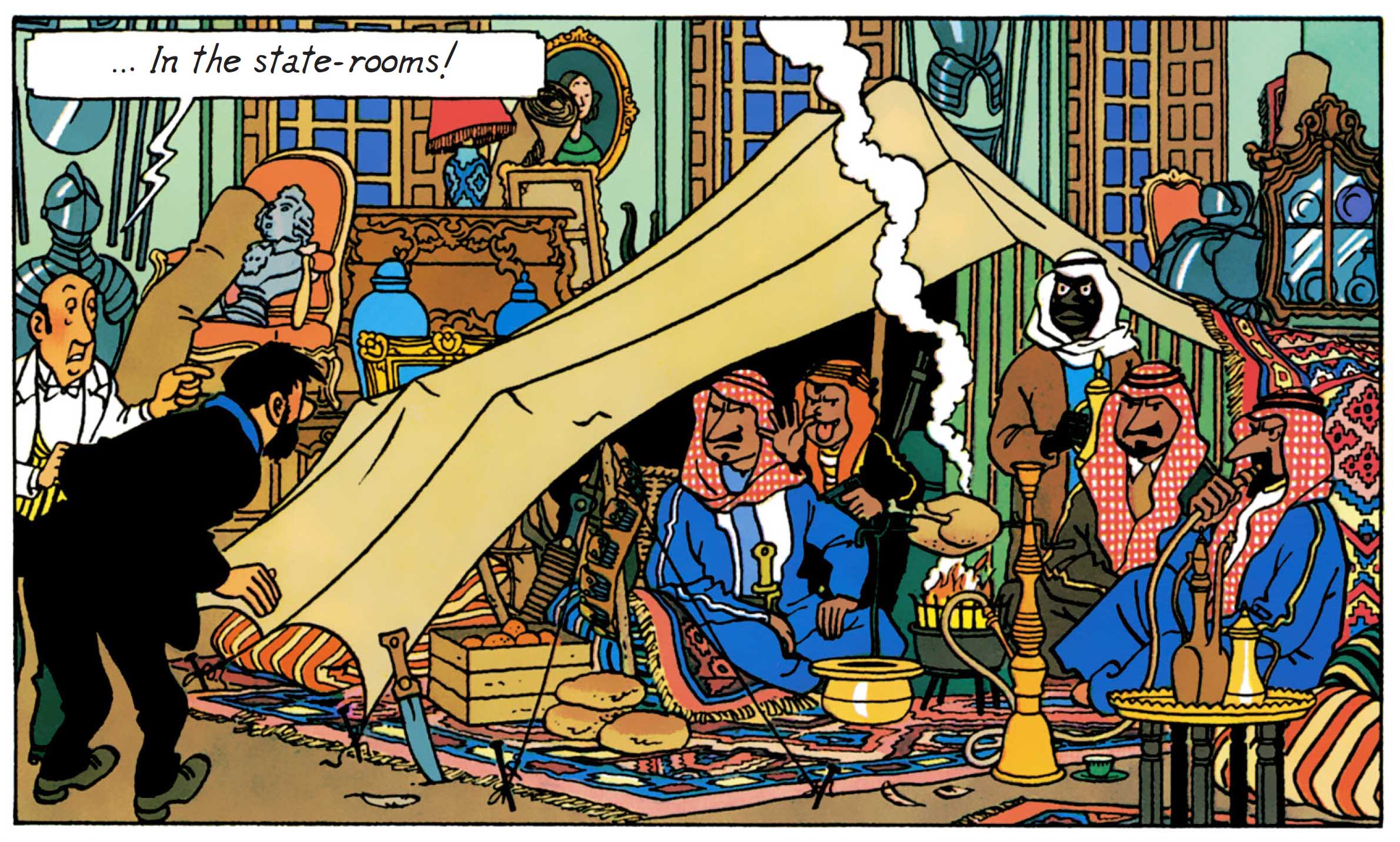

And if he doesn't go to foreign culinary practices, they come to him... or rather, invite themselves into his friend’s home, as is the case in The Red Sea Sharks, when the men of Emir Mohammed Ben Kalish Ezab take over Captain Haddock's living room to set up - as they usually do in the desert - a Berber tent. A pretty little corner of Arabia under the gilding of Marlinspike Hall. A change of scenery and good roasted food guaranteed!

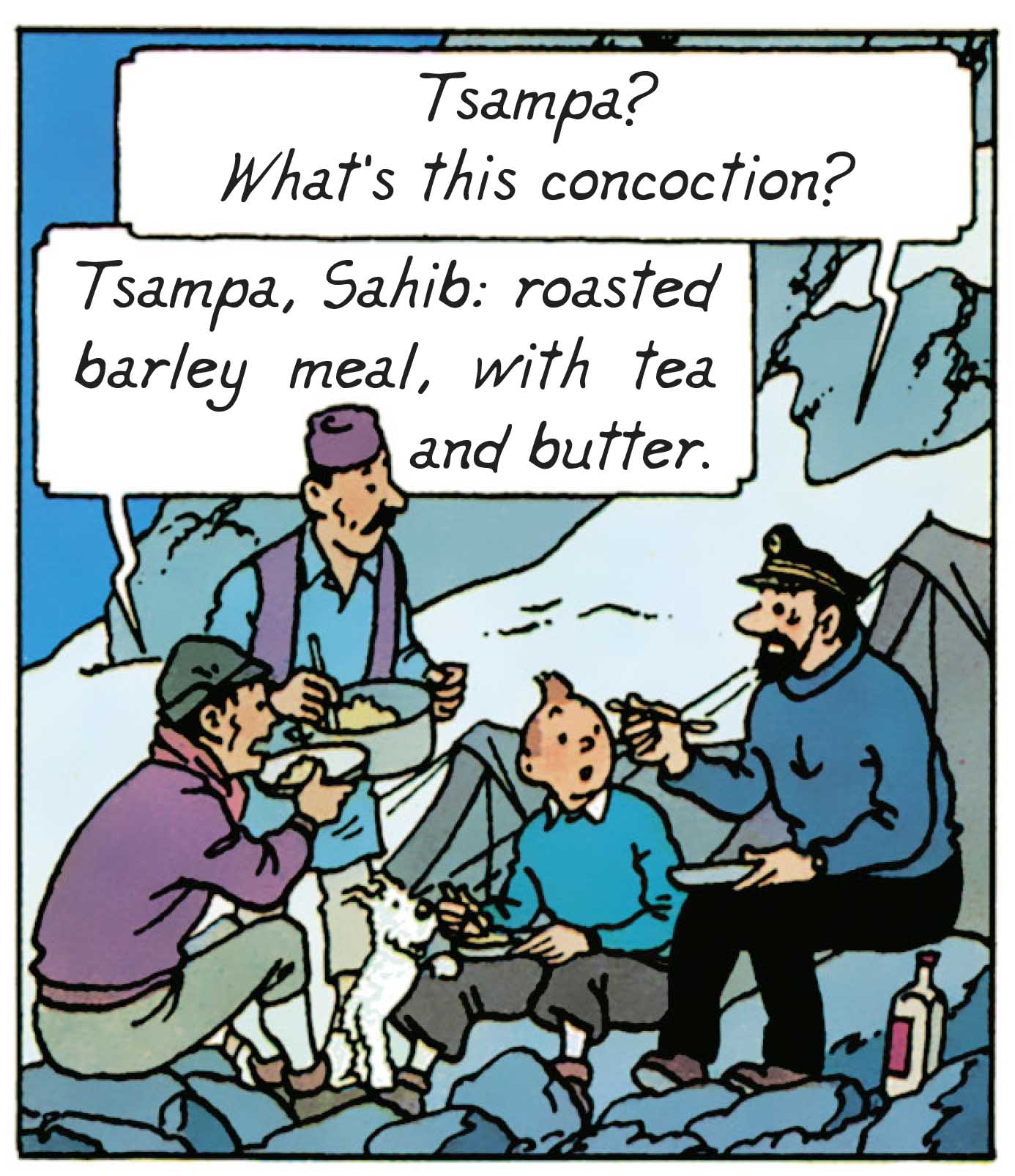

In his geo-taste tour of the world, Tintin always makes a point of sampling local specialities, even in the most remote or unusual places. So it was on the mountaintops, during his journey to the land of the Yeti, that he tried Tibetan cuisine for the first time. In this case, Tsampa. This easy-to-preserve and transportable dish lends itself well to impromptu picnics at high altitudes.

Let's face it, the young man is a gourmet whose taste buds are constantly aroused. In fact, he's always ready to try out new flavours, even if they're sometimes too spicy. Sensitive palates abstain... " You may not like it, but pretend you do: you don't want to offend them", Ridgewell gently tells him, before he tastes the otnôsh seasoned with Picaros sauce. Caramba! In spite of the warning, he can't help but blush and spit fire. A word of advice: don't overdo the good stuff, especially when it comes to spices. Otherwise, you run the risk of tastelessness.

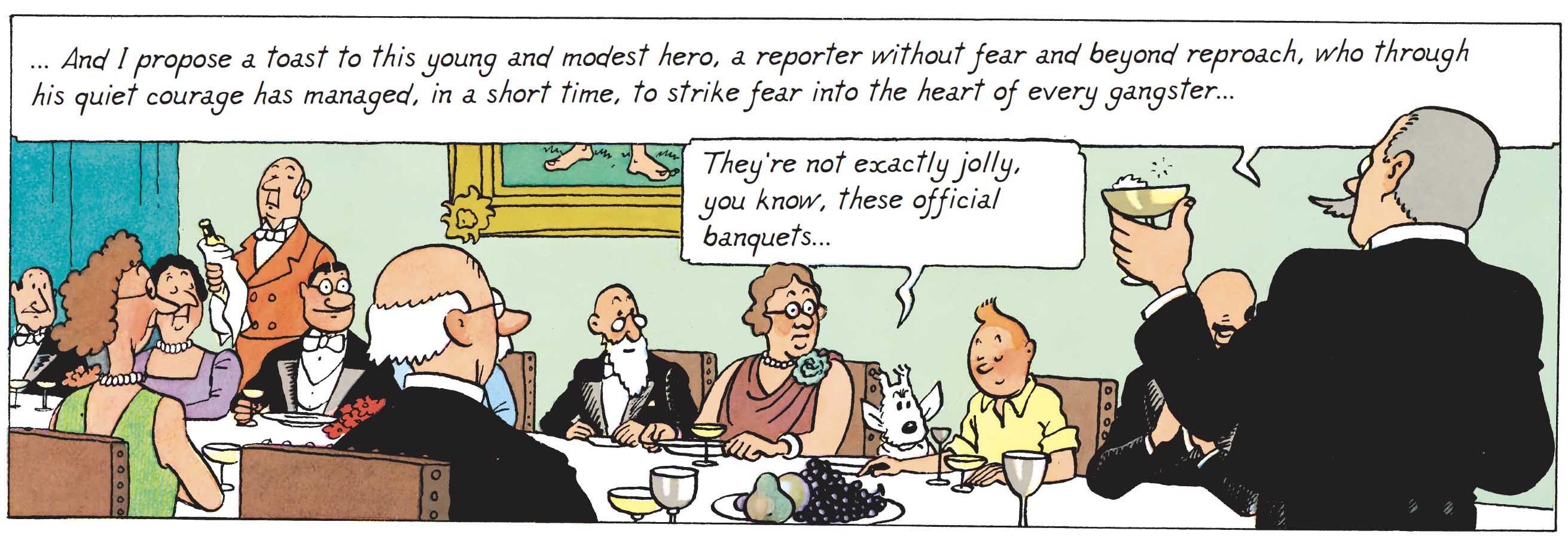

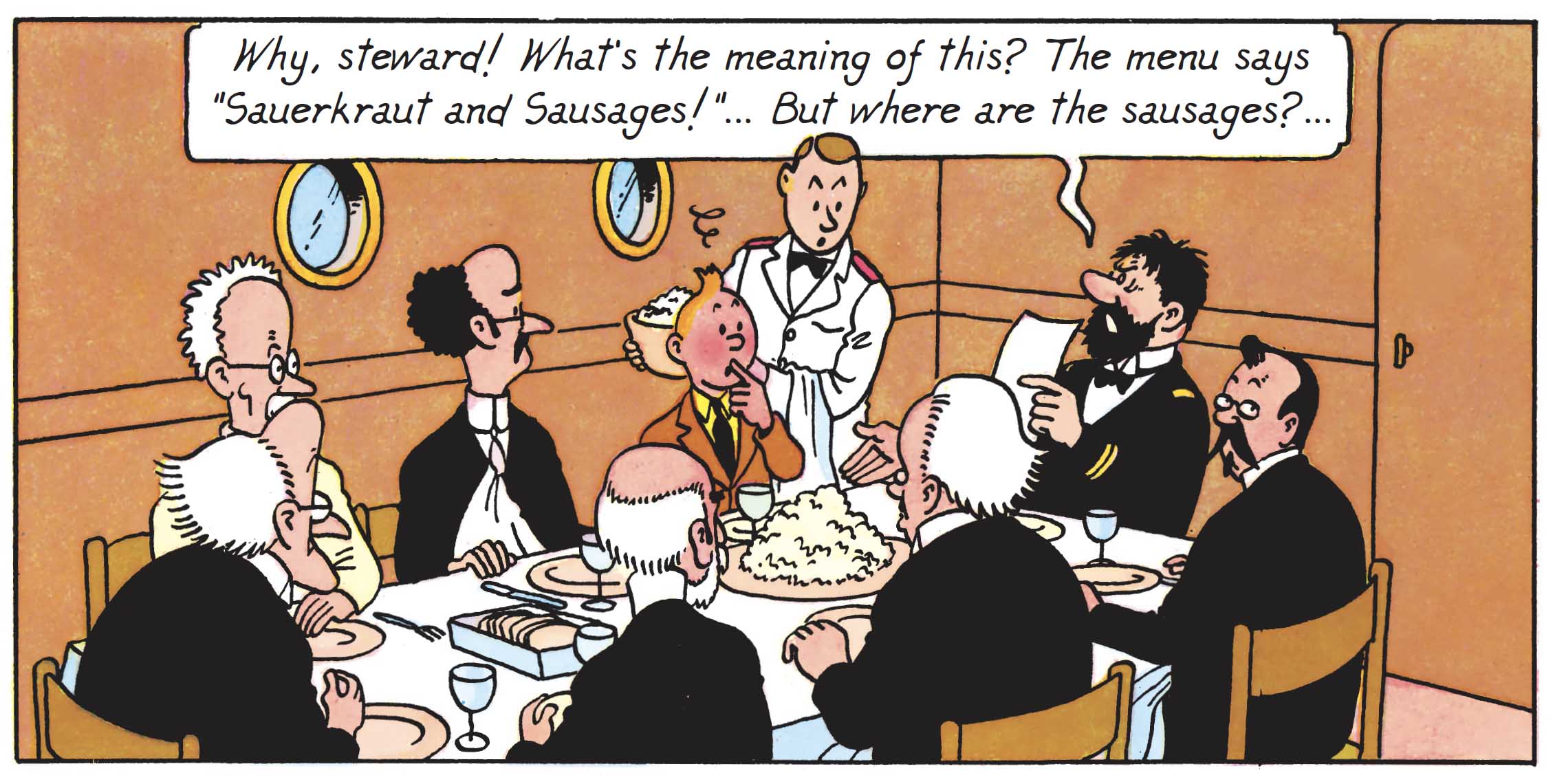

After all, what would a table be without its guests, if not "a dessert without cheese", to quote Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin. Without them, the Last Supper... er, the scene, would not be perfect. For, beyond its food function, eating is a social activity in its own right. In fact, we rarely eat alone. Except by choice or necessity. So, even if "the more the merrier, the less the rice" - as Coluche put it - it's better to be in a group when it comes to sustenance. In The Shooting Star, for example, the "almost garnished" sauerkraut brings everyone together as the scientific expedition heads for the Arctic seas.

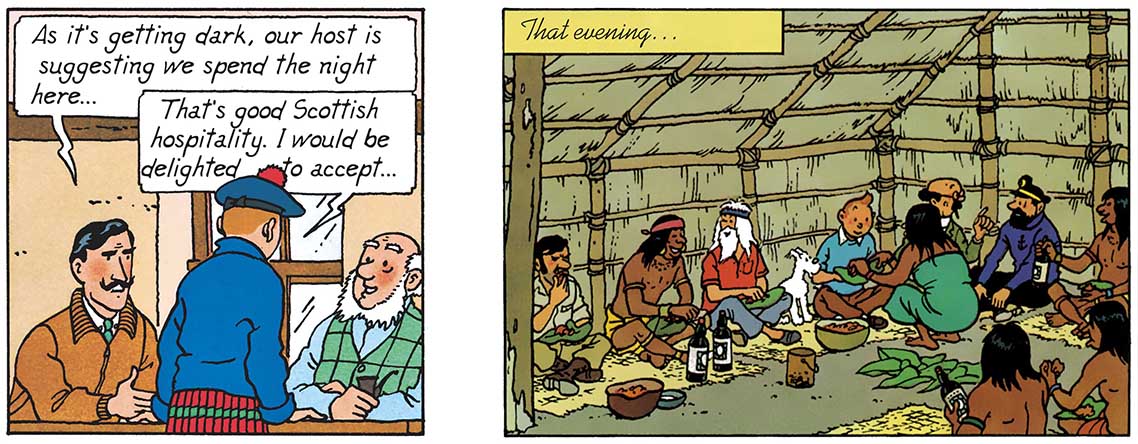

Where there's friendliness, there's usually hospitality, as the two concepts often go hand in hand. So it's hardly surprising that in The Black Island, Tintin is warmly received - and welcomed, too - by the proprietor of an inn. The innkeeper offers him clothes, room and board. Enough to get him back on his feet after a chaotic, bumpy flight. When it comes to hospitality, the Picaros are not to be outdone either, as it's in the hut of the Kaloma chief that he is received as a guest of honour, in the company of his faithful acolytes. Each meal shared with the local people is a golden opportunity to forge strong socio-cultural links. Strong because respectful, fraternal and sincere.

Oh, and one last tip to make dinner almost perfect... especially if you're a guest: before you leave the table, don't forget to clear it!

Texts and pictures © Hergé / Tintinimaginatio - 2024

News

News Forums

Forums E-books

E-books